Precursors to Modernity: Arts and Crafts:

Arts & Crafts

In 1851 in London, in Hyde Park to be precise, in a huge glass palace that looked like an overgrown greenhouse, The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations opened on the first of May. Planned and executed by Henry Cole (1808-1882) and Queen Victoria’s consort, Prince Albert (1819-1861), the Great Exhibition, as it was called, was an enormous success. Inspired by the French Industrial Exhibition of 1844, the English event was the first to be international in scope. “Industrial exhibitions” had been held since the end of the eighteenth century, the beginnings of the industrial revolution, but these had been local affairs, confined to the interests of a particular nation. But Prince Albert wanted to not only compete with the success of the 1844 exhibition but also to surpass it, by being “not merely national in its scope and benefits, but comprehensive of the whole world.” The Crystal Palace, which spanned nineteen acres, held objects large and small, natural and unnatural, manufactured and hand-made. Inside the huge expanse of iron and glass, designed by Joseph Paxton (1803-1865), the open space was divided into four spaces or areas devoted to raw materials–where one could see a giant lump of coal, machinery—the place where the famous McCormick Reaping Machine was crouched and grinding away, along with manufactures–a catch-all category, and fine arts. A contemporary account, A Popular Narrative Of The Origin, History, Progress And Prospects Of The Great Industrial Exhibition, 1851, by Peter Berlyn described the show-and-tell aspect of this Exhibition: “In a word, every one may be able to see how cloth is made for his clothes, leather for boots, linen for shirts, silk for gowns, ribbons, and handkerchiefs; how lace is made; how a pin and needle, a button, a knife, a sheet of paper, a ball of thread, a nail, a screw, a pair of stockings are made, how a carpet is woven.”

Apparently feeling challenged by Prince Albert’s invitation, the nation of France arrived and unloaded an impressive number of offerings to impress the British and their visitors. Some accounts decided that in the area of applied arts and decoration, not to mention the fine arts, France surpassed England on its own turf, even in the area of fabrics, a craft that the British prided themselves on. The Exhibition of 1851 revealed that England was dominate in the industrial revolution, with its only rival being America, but in the realm of taste and artistry, France continued its elegant domination. To be fair, which nation could compete with Limoges enamels, Lyon silks, and Sèvres procelain? There are completing urban legends about the reaction of a young teenage William Morris (1834-1896), who arrived at Hyde Park with his parents. One at the site, young Morris, already a sensitive soul, either refused to go inside or actually attended, only to rush out and vomit in nearby vegetation. Whatever the precise truth, the precocious Morris appears to have been distressed at the impact of manufacture on craft and the resulting decline in artistry. Manufactured goods were impacting the aesthetics of the handmade with a resulting decline in taste. Inspired, and not in a good way, William Morris, who described the contents of the Palace as “wonderfully ugly,” dedicated his adult life to reforming Victorian taste and to bring back the art of craft as an artist within a collective of like minded artists.

William Morris. Stanmore Hall (1891)

One of the paradoxical oddities of the Exhibition were the very modern machines that were encrusted, as if to disguise their modernity, with ancient motifs, from Doric columns to Gothic tracery. In fact, decoration, an abundance of it, became the leitmotif of the Victorian era, and the excess of embellishment was used to disguise shoddy manufacture. “Shoddy” in this context does not necessarily refer to the stability or sturdiness of a piece of furniture but to the neglect of craft. For example, the Exhibition featured a church screen carved by Jorden’s Patent Mechanism. According to the premier art critic of Great Britain, John Ruskin (1819-1900), ornamentation should be expressed through the hand and by human endeavor only. Using a machine as a substitute for learned artistry lowers the raison d’être of decoration. For Ruskin, a machine carved object was unworthy of consideration as an aesthetic object not because of its design but because of its deceit—it pretended to be hand made and the entire object was a lie. In discussing the reception of the exhibition, Nikolaus Pevsner, the historian of design, noted in his discussion of the home furnishings on display, including the new trend in papier maché as a wood substitute, and brass and hollow tubed beds, which were elaborated adorned, that “The pieces are rightly called in the caption ‘ornamental furniture’, and their style can once again serve as an example of what the mid-nineteenth century demanded from its furnishings. All curves are eminently generous, all outlines broken or blurred, and a general tendency to top-heaviness is essential to the authentic effect.”

Pevsner, who was writing in 1951, was the first historian in decades to discuss the discourse that surrounded the Victorian taste that presided over the Exhibition. At the time of the Exhibition, there were dissenters, other than William Morris, who complained of the excess in surface decoration. It seemed as if the manufacturers were fearful that the substitution of modern materials for traditional substances might be noticed if the object remained naked or uncloaked. The public had not yet developed a taste for the honest expression of the manufactured material whether it be the novel use of zinc at the Exhibition or historical iron. Even the Crystal Palace, an aggressive assertion that iron on its own, combined with the contrast of glass could be a dazzling feat of architecture, would not be fully appreciated for decades. And, it can also be posited that the manufacturers also wanted to demonstrate the virtuosity of their talented machines. Unique to Victorian design, was the presence of the curve, whether in the fashionable clothes for women or on the sofas they sat on. As Pevsner wrote in his book, High Victorian Design: A Study of Exhibits of 1851, “A universal replacement of the straight line by the curve is one of the chief characteristics of mid-Victorian design. As against other styles favouring curves, the Victorian curve is generous, full or, as has been said more than once before, bulgy. It represents, and appealed to, a prospering, well-fed, self-confident class. A peculiar top-heaviness often to be met is only a special case of this delight in abundant protuberances. Another hallmark of 1850 is equally telling. There must be decoration in the flat or in thick relief all over all available surfaces. This obviously enhances the effect of wealth. Critics of Victorian design have not always recognized these basic qualities, deceived sometimes by dislike, sometimes more recently by a nostalgia in revolt against the austerity of twentieth-century shapes and surfaces, and some times by the fact that the mid-Victorian style rarely appears without a historical costume.”

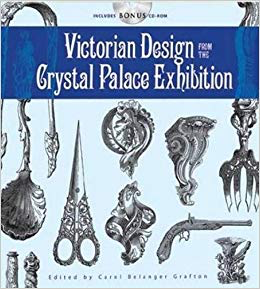

Victorian Design from the Crystal Palace Exhibition

Pevsner made an interesting point on the characteristics of Victorian design beyond the observation of what Henry Cole referred to as it “bulges,” and that was the eclecticism of its historicism. Mid to late century European and American design had no style of its own and the second half of the century was marked by a return to the past, to architectural references as expressed by elements or fragments removed from their original context and assembled together without regard to chronology or culture. The non-style was a hodge-podge of of quotations that reduced architecture to a façade covered with appropriations from post civilizations. The same process was also applied to furniture and over time, exterior and interior ornamentation became a “style” for the Victorian period in the sense of a recurring set of motifs or practices. Pevsner also mentioned the overwhelming experience of curves and bulges and swellings and curvilinear twirls that were the signature look to interior design. Understanding what would later be referred to as the “bad taste” or excess or surplus of decoration of Victorian design allows us to grasp the urgency of the design reformers who believed in “truth to materials” and rectified the bulges either though Art Nouveau discipline and exaggeration and conversely, with re-introduction of the straight line. In addition, the later desire for a clean surface is fathomable in light of the precursor preference for coverings of all kinds over all objects. The saving grace of the overly decorated–for our contemporary tastes–consumer goods was that these products were affordable.

Ubiquitous and embedded in popular culture, Victorian design was mostly a middle-class phenomenon. By the middle of the nineteenth century, this class had amassed enough financial security to build or purchase homes and to furnish these proud new domains. Today, home decorating seems a simple enough enterprise, but, a century ago, this step was fraught with danger. The nobility had accumulated “furnishings” over decades or centuries and any noble home or country estate was filled with aged and mellowed pieces, each perhaps with a history attached. The middle class, in contrast, had no such family treasures and were forced to purchase new objects that were mass produced. To merely buy items for a new home was to reveal oneself as being without an old family, without educated taste and without aristocratic refinement. The snobs might have shuddered but the guileless homeowners packed their rooms with a mad variety of manufactured objects covering all available surfaces, floors, walls and ceilings. The horrors of such accumulation, often festooned by protective doilies which laid upon sofa arms and table tops, their lacy designs fighting off soot and dirty air, were painful to the eyes of the artistically aware. In their anxiety to appear to be respectable, the Victorian buyers sought copies of historical furniture styles and jammed the faux objects into their homes.

The Drawing Room of Tyntesfield, photographed in 1878

As seen in this drawing room of the 1870s, the cacophony of the typical Victorian parlor inspired the Arts and Crafts Movement led by William Morris, who spent his life attempting to reform English standards. Morris urged a return, not to “good taste,” but the ideals and standards of craft as an art form in and of itself. Much of the work of Morris and his artistic associates, such as Edmund Burne-Jones (1833-1898), was inspired by medievalism and was, therefore, not modern, either in design or approach. But the notion that the domestic setting should be an aesthetic experience inspired the successor to Morris’s Arts and Crafts: the Aesthetic Movement in which artists, such as the American expatriate painter, James Abbot McNeill Whistler (1843-1903) brought a more up-to-date approach to the modern home. Whistler’s ideas were radical for their time in that he abandoned the elaborate wall paper designs of William Morris in preference for plain walls washed with pale color. In contrast, Whistler’s furniture designs, created in collaboration with Edward William Godwin (1833-1886), were elaborate and complex in design. It would take decades for the late nineteenth century designers and their public to accept the simplicity that would be the hallmark of the twentieth century. Nevertheless, these early attempts at reform of design and craft laid the foundations for a simplification of interiors, a streamlining of furnishings and a coordination of colors that would be carried on into the new century by new designers.

Edward Godwin and James Whistler. Harmony in Yellow and Gold:

The Butterfly Cabinet (1877-1878)