Solo exhibition of the Photographic Work of James Higginson

Behold. Perspective at Play in a Young Man’s Mind

Haus am Kleistpark, Berlin

Photographic Exhibition from March-May 2015

Unless one is an angel, descending from on high, no one without wings utters the word “Behold” any more. With all its well rounded “ohs” and Biblical and Koranic implications, “Behold” as a command has almost faded from contemporary vocabulary. Behold is an order and an imperious one at that. Behold expands far beyond the causal imperative of “look” or “see” or “view”–behold implies a serious contemplation of a significant unveiling. A revelation is at hand, and a revelation is the disclosure of something previously unknown, a fact that has been hidden or a situation kept secret or a condition previously unknown. A veil will be raised, a curtain will be lifted, a light will be lit and now all will be exposed to astonished eyes. The drama of “behold” suits well the notoriously vivid and astonishing photography of James Higginson, who has made a career of making us look at society’s purloined letters, is lying in plain sight.

To “Behold” is to be witness to what is at play in the mind of a young man and Higginson is the guide who provides the perspective. A photographer, who turns the camera against itself to create fantasies that tell truths too potent to face without disguise, Higginson manipulates and directs his subjects who are actors, displaying elaborate artifices and social constructions. The male, Higginson’s photographic suites insist, is inauthentic, a construct, a tabula rasa who self-constructs into fictions that are forms of exaggerated play on the game of being male. None of the men in this large beautifully mounted exhibition are middle-aged or set in their ways, so to speak, none are old, formed, congealed and hardened into an indelible mold. All are young or wanting to be young, actively engaged in shaping themselves, using the allegorical tools, such as they are, provided by society.

These tools are like toys in a child’s closet, repetitive and limited and yet capable of astonishing variation at the hands of an imaginative young man, who learns very early in life that life is a series of costumes, poses and performances. Being a man is a performance, that much is well known, but what Higginson emphasizes is that the exaggeration of masculinity is a forcing of masculine extremes in the face of flaunted femininity. The artist shows very clearly what can and cannot be revealed: the soul. The body of work from which the exhibition takes its name, Behold (2010), is powerful in its intimacy. Higginson shows the heart of the male, stripped of clothes and posturing, signified as a naked back, a male version of The Bather of Valpinçon (1808) and re-marked as a male obsession with forbidden voluptuousness. Where Ingres caressed with his eyes not his hands, where Ingres touched with his brush, Higginson embraces his vulnerable model, back bare and exposed, with an enveloping black robe which reaches around and holds like a hand in a dark glove. But we must recall that Higginson is always subtly sarcastic in his approach to photography, for what seems to be a dark embrace is actually something much more Ingres-esque–the black is actually paint on skin, a shadow of a touch, an illusion of togetherness. Behold is almost embarrassingly revelatory, full of yearning and desire, a statement of need to be loved, to be touched, all of which must be concealed by the mask of men who must be invulnerable and strident in a male world where all must be hidden.

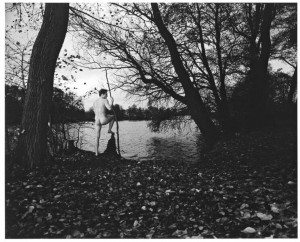

Closely related to Behold, is the series Interlude (2004), a prolonged study of male helplessness in an indifferent world. Higginson presents the young man adrift in nature, set nude in bucolic nature, naked in the woods. Like Adam, bewildered and alone in the Garden of Eden, the young men linger at the edge a lake, staring across the still waters. Unlike Behold which is in painfully personal deep color, Interlude is deliberately subdued in black and white, denied silvers and devoid of uplifting whites, except for the blank enigmatic skies. Although the American artists lives and works in Germany, there is nothing of the heedless pre-war nude frolics of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner at Moritzburg and nothing of the portentous pantheistic grandeur of Caspar David Friedrich in these photographs. It is rather as if Robert Adams were God who placed an unwitting Adam in an anonymous wood and left him to his own untutored devices. These young man are modern, lost and alone, stripped of clothing and of any accouterments of survival. They attempt relaxed or assertive postures but they are classical nudes stranded in a rather sharp-edged forest, stripped of halcyon tones and bristling with future wounds to the pale slim bodies. They are vulnerable because of their age, they are still malleable. Still in states of becoming, the minds of these young men are still in play.

The young man learns to put away the blanket of comfort and childhood and gives up all thought of emotion and is taught to don the costume of maleness or manhood. Since the ancient Romans, puritanical society has commanded men to put on full body armor, a costume of concealment, whether it be the long enveloping robes of a priest or the tense suit of a businessman. Nothing must be allowed to escape, not an errant ankle or stray emotion. Exposure is vulnerability, Higginson suggests, and no one likes to be left alone in the prickly forest. Gender becomes the shield and spear against the traumas of the natural. As Judith Butler noted,

Gender is the repeated stylization of the body, a set of repeated acts within a highly rigid regulatory frame that congeal over time to produce the appearance of sub- stance, of a natural sort of being.

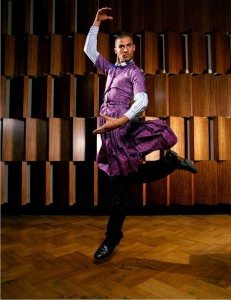

In her well-known book, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1990), Butler used the words “compulsory” and “regulatory” to demonstrate the constricting effect of language has on the human subject, halting the impulse to play. Suggestion that gender is a social performance which becomes an understudy, taking the place of the “real” person who disappears from the stage. If, as Butler insists, there is no getting outside the discourse of gender, then it is possible to contest the discursive rigidity of “manhood” with the loose linguistics playful clothing. In his series on male attire, the artist resists Butler’s nihilistic theories with the absurdity of fantasy costume in Goth (2009) and in the precision of historical costumes seen in Black Shields (2012). The Black Shields or Georgian Fight Art Federation Shavparosnebi are unfamiliar to American audiences but in the summer of 2015, this group of re-enactors won first place at the first place at the Natale di Roma festival. Since 2012 Georgia, once part of the Roman Empire, has been part of this annual event and the Shavparosnebi demonstrate Georgian fighting techniques, traditional clothing and weapons. The Shavparosnebi represent serious manhood at the extremes, if you will, at the peak of the Roman Empire, an age still celebrated by Hollywood. The fighting men of the Shavparosnebi re-enactors, charged with conserving an obscure but proud culture, pose proudly, conquered and yet always authentic. These modern men, now living in the dangerous shadow of Russia, choose to don the costumes of their ancient counterparts and relive a more glorious past–also lived at the mercy of a greater power. Thus cultural pride provides an assertive stance and a stage upon which to perform manhood.

These alternative self-fashioning are playful antidotes to conservative submissiveness to the characters written in preexisting scripts. In HWD Dresses and in the delightful HWD Dresses in Action (2009), Higginson puts men in female clothing to see what happens. Perhaps it takes men wearing women’s clothing to make the familiar strange and to demonstrate the dislocation that a simple act of switching costumes can cause in a well ordered society.

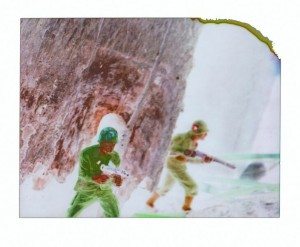

As if stressing the importance of play in the young men’s mind, Higginson closes in on the tiny toy soldier, khaki green and plastic, wearing camouflage for an imaginary jungle campaign. It is here, in the playroom, that the boy learns to be a man and these simple plastic figures, fighting in bleached out spaces of a photographic field, teach manhood through violence. As he imaginatively enters into the mental space of a fighting man, the boy learns to pretend to fight and kill and even die in the performance of his gender to come, gender to be. There is an active submission and strident compliance in his unthinking conformity to cultural concerns: that there be males to confront females, constructed as each other’s polar opposites. In today’s world, where gender roles are breaking down and men are taking more active part in the nurturing business of parenting and women are in Afghanistan are fighting and dying, Higginson’s pointed commentary on the straightjacket of social norms seems well placed and necessary.

Wisely, the artist refuses to patronize his audience with the obvious commentary on gender roles. Perhaps twenty years ago, such preaching would have been novel, but today, Judith Butler is long out of date. The artist has been working for the past fifteen years, using the directorial mode of photography to demonstrate the charade of gender. Turning performance inside out, Higginson forces his actors to take off their accustomed clothing and to explore other states of being. In the process, he finds a simple truth: before we are anything else, male or female, we are human beings, naked and desiring, alone in the world. In the photographic universe of James Higginson, to play is to think, to think is to gain perspective, to reveal is to behold.