British Propaganda and Women

The Psychology of Posters

Warfare, especially modern war, has had a strange impact upon men. It is assumed that war and combat is the ultimate event of masculinization, completing the identity of the male. Traditionally, the equation of hyper masculinity and the military had been fairly reliable in the nineteenth century. Wars were fought elsewhere, out of the public eye, with the early war correspondents willing to find heroes who were “mentioned in the dispatches,” even in unpopular wars like that in Crimea. Normally this war is thought of as one that limped to an end, while the British government colluded to conceal the military blunders and mismanagement, but, in an interesting article in The Guardian, Orlando Figes, author of The Crimean War: A History, made a case for the Crimean War as a conflict that created new heroes. While Alfred, Lord Tennyson, mourned and celebrated the anachronistic folly of the “Charge of the Light Brigade,” the British press was pointing angrily to the result of the class system. The rigid class system that ruled civilian society also formed the military hierarchies and would continue to do so through the Great War. The privileged ruling class ruled with the second sons of titled nobility crowding the ranks of those in charge whether or not they merited or deserved their elevation to power and responsibility. The men of the growing middle class became more prominent during this war, if only in contrast to the incompetence of the exalted officer corps.

As Figes pointed out, “..the public meaning of the war” was fixed by middle class “journalists and pamphleteers, poets, artists and photographers, orators and priests. This was the first “modern” war in the age of mass communications – the first to be photographed, the first to use the telegraph, the first “newspaper war” – and it shaped our national consciousness.” These observers in the newly emerging mass media took an objective perspective on a war that was being fought for no discernible reason, revealing folly and heroism. Figes continued, “The mismanagement triggered a new assertiveness in the middle classes, which rallied round the principles of professional competence, industry, meritocracy and self-reliance in opposition to the privilege of birth. It was a sign of their triumph that in the decades afterwards, Conservative and Liberal governments alike introduced reforms promoting these ideals (the extension of public schooling, opening of the Civil Service, a new system of merit-based promotion in the armed services, etc). The political scramble for Middle England had begun.” The middle class soldiers shone in comparison to their aristocratic superiors: “..the heroes who returned from Crimea were the common troops. Their deeds were recognised for the first time in 1857, when Queen Victoria instituted the Victoria Cross, awarded to gallant servicemen regardless of class or rank. Among the first recipients of Britain’s highest military honour were 16 privates from the army, five gunners, two seamen and three boatswains.”

The Great War was the first war that impacted upon the consciousness of the British public since the Crimean War and war, over five decades had changed enormously. And so too had the role of women in British society. During the 1850s, it was Florence Nightingale and Mary Jane Seacole, who defined convention and became the women who established military nursing–the care and healing of the wounded soldier. Even in the hands of a woman, the wounded British male retained his masculinity and it was important for the nation to celebrate his heroism, especially in light of the War’s failures reported in excruciating detail by William Howard Russell. The women who nursed the men also became heroes, apparently without threatening the manliness of the men. Writing in 1878, in Heroes of Britain in Peace and War, Edwin Hodder explained, “..in our hospitals there is a noble army of brave women who are devoting themselves the to care of he sick; women, who not finding a sphere for labour in their home circles, and feeling the burden of humanity claiming their sympathy, have gone as heroically and in some instances more so, to labour among the sick in the hospitals of crowded cities as others have gone to tend the wounded and dying on the battlefield..” It can be assumed that nursing as a form of nurturing fell into the bounds of expected and accepted behavior for women, and it is clear that two decades later, the shock of women invading the precincts of medicine had worn off.

But the woman of 1914 was a different social person, living in a British society in which the middle classes were educated and ambitious. As Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth (1933) attests, nineteenth century attitudes still prevailed in an increasingly modern world, with the ruling class of males deliberately holding aspiring women back. For decades, after the Crimean War, women had been campaigning for the right to vote. As in America, at the same time, the movement broke into two separate sectors, one conservative and willing to wait patiently, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, and one more militant and more impatient, Women’s Social and Political Union. As in America, the WSPU under the leadership of the Pankhurst women, mother and daughters, women were put in jail and stubbornly refused to eat. As with Alice Paul in America, the British women were force fed, a form of torture in those days. When the Great War began, the suffrage movement redirected its efforts towards working to win the war and thus prove women worthy of being given the right to vote.

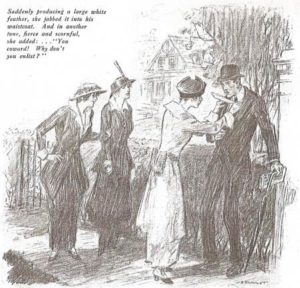

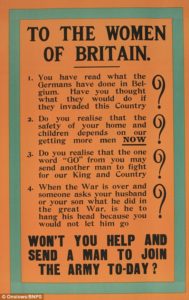

It is against this political background that one understands the propagandistic efforts to encourage male enlistment in a deadly war. While at first, outraged by the invasion and “rape” of Belgium, men eagerly signed up, recruitment efforts flagged and atrocity propaganda could not inspire sufficient enlistment. The government embarked on another other approach, which was a play or a variation on the demanding Lord Kirchner poster–public shame. In what might be called the descendant of the “white feather” campaigns, men were shamed into playing a part in the war of attrition. The idea of the white feather can be dated back to the days of cock fighting in the eighteenth century. When a defeated cock “turned tail,” revealing the white feathers beneath his plumage, he was signaling refusal to fight, advertising defeat. The transference of the the meaning of a white feather to the practice of handing out white feathers to men considered cowards was popularized by the English writer A. E. W. Mason in his famous 1902 book, The Four Feathers. Written during the Boer War, this novel was a shameless advertisement for imperialism in which a young military officer who preferred not to serve the Empire was presented by four white feathers from his fiancée and his close friends. The entire novel is an adventure story in which the shamed young man, Harry Faversham, has to redeem himself, save his friends and win back the woman he loves, all while in the service of the Empire. The popular story (which has been made into at least six films) laid the groundwork for the White Feather Campaign during the Great War.

This campaign of public shaming men out of uniform was begun at the end of August 1914 by Admiral Charles Fitzgerald who advocated compulsory military service. He organized the White Feather Campaign in Folkstone and recruited young women to hand out white feathers, also a sign of an inbred cockerel unfit to fight, to young men out of uniform. The timing was fortuitous: the suffrage movement was on hold and young women had high expectations of being of service. At the early stages of the War, women were given nothing of use to do and many, particularly the young ones who had not raised a child, leaped at the chance to participate as patriots. But, in the process, many young men were shamed and suffered for decades over the public humiliation. As Peter J. Hart wrote in “The White Feather Campaign: A Struggle with Masculinity During World War I,”

The Campaign worked fairly well and by shaming Home front men, these women drove many into the army out of dread of receiving a white feather themselves. But an unexpected consequence arose from this attack upon Englishmen’s masculinity, one that these “patriotic” women didn’t foresee. As this campaign became more public and recognized, the community backlash against women who engaged in this practice became increasingly harsh. Englishwomen had been molded into a weapon against the masculine identity through propaganda and promises of patriotism.

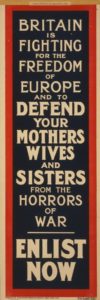

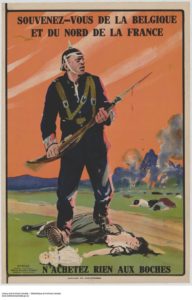

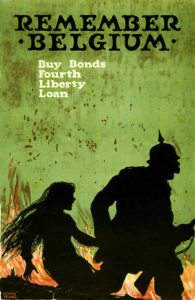

There were compelling reasons why women echoed the shaming campaign of the propaganda posters. Given that the War had began during the long and violent Suffragette Campaign during which the British government stalwartly resisted the demand that women be given the right to vote, women would react with alarm to the horrors inflicted on the women of Belgium. The attack of the Germans upon helpless Belgium was the main reason the British entered the War and the women of Belgium had suffered terribly from the German army. The stories that swirled around the atrocities were so graphic and, at times, so exaggerated, that for decades it was thought that the tales could not be true. But revisionist history, searching though German Belgium archives has established that the atrocities committed in Belgium were very real indeed, even accounting for the inevitable tall tales circulated during wartime. For British women, the stories of how the Germans treated the women of Belgium were terrifying and they felt justified in urging men to avenge these female victims. But, perhaps more importantly, the women could take on the role of responsible citizens, doing their part and fighting the War in their own way. Not unexpectedly, the White Feather Campaign, which activated women, resulted in women being criticized for what they were asked to do. The criticism was based, not in the idea that they might be unjustly shaming an undeserving man, but on the grounds of “immodesty,” meaning that women were aggressively approaching men and imputing their masculinity.

Nevertheless, women were merely echoing a broader campaign of shaming, raised repeatedly by the press and mass media, driven by the desperate need for males to fight the long war. Nicoletta F. Gullace wrote that poet John Oxenham wrote a special poem directed to women, calling them to their duty:

O maids, and mothers of the race,

And of the race that is to be

To you is given in these dark days

A vast responsibility….

Remember!—as you bear you now,

So Britain’s future shall be great

—Or small. To your true hearts is

given a sovereign duty to the state.

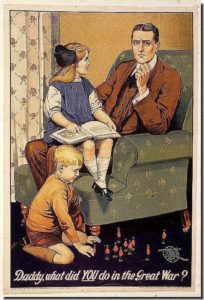

In her article “White Feathers and Wounded Men: Female Patriotism and the Memory of the Great War,” Gullac quote the approving words of the Mayor of London, directed towards women: “Is your ‘Best Boy’ wearing Khaki?…If not don’t YOU THINK he should be? If he does not think that you and your country are worth fighting for—do you think he is worthy of you? Don’t pity the girl who is alone—her young man is probably a soldier—fighting for her and her country—and for You. If your young man neglects his duty to his King and Country, the time may come when he will Neglect You. Think it over—then ask him to JOIN THE ARMY TO DAY!” The point is that the women who participated in the “Order of the White Feather,” had wide public support and wives and mothers and sweethearts were exhorted by mass media and by propaganda posters to reject men who would not join the military. Men were also directly addressed by the propaganda posters, which also employed a tactic of shame, implying a dereliction of duty and suggesting that their own families would reject them if they did not do their duty.

In his 2012 book Britain and World War One, Alan G. V. Simmonds explained how these shaming tactics were shaped by government propaganda: “..what began as a politicians’ and diplomats’ war declared for reasons of economic security and European hegemony became a struggle for national unity, civilization, liberty and for the protection of Britain’s Empire and her essentially Victorian way of life. The threat of all of this was a powerful reason for men to enlist, but it proved insufficient to satisfy the Army’s ever-growing need for recruits.” One of the earlier attempts at blackmailing men into joining the military was the innocent sounding Pals Battalions, which, as Simmonds expressed it, “successfully embodied powerful forces of peer pressure and civic pride. Groups of men, linked by a common bond of professional, recreational or emotional ties, were encouraged to join up together in units that combined a strong sense of local identity with group solidarity, along with an opportunity to exploit alternative loyalties for which to fight other than ‘King and Country.'” Another way of explaining the Pals’ Battalions was a way to encourage young men who were not necessarily invested in the British Empire to join up. These recruits would more likely be middle class but without the public school privileges enjoyed by the upper ranks and the working classes who owed little to what was a campaign to preserve the power of the upper classes.

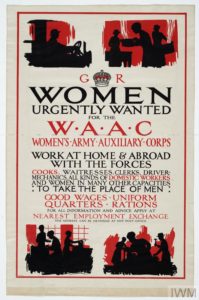

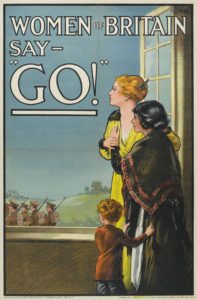

Involving women was an ideal way of activating women of all classes who would be encouraged to hand out white feathers to the men they encountered. Lower class men could be directly confronted; middle class men shamed at home. Every woman had a network of male relatives who could not ignore the devices of the White Feather brigades. The result of the campaign in which women were asked to participate directly or indirectly was nothing short of emotional blackmail. The government recruited women, as much as it recruited men, as participants in the War, asking them to send away their husbands, fathers, brothers, and sons to a war from which many would not return or would return wounded in body or mind or both. The constant drumbeat of these early posters, issued before the Military Service Act in 1916 started forced conscription, emphasizes the inherent unnaturalness of war. Men and women had to be forcibly manipulated by a constant drumbeat of obligation with an underlying threat of being de-masculinized. This threat manifested itself in reality as conscription resulted in more and more men disappearing from the Home Front and into the military. Women began to take their place everywhere, in the factories, in the offices, in the hospitals, even wearing uniforms as police officers. The wartime posters began to address women, urging them to join the war effort and to take the places of men, whether driving buses or playing football.

The Great War utterly changed women, propelling them headlong into the twentieth century, proving that they could succeed at the very jobs men had insisted they could not do. Of course, when the War was over, the women were sent home to make room for the returning males. But, as with the Second World War, women would not forget their wartime experiences Unlike World War II, an entire generation of men never returned. After the Great War, women were widowed or were nursing men with permanent wounds, and there were those women who would never marry. This new independence was played out by their younger sisters who became “flappers,” who refused to live the lives of their mothers. For men, the Great War had begun as a noble cause, a fight for King and Country of for one’s closest friends; for women the Great War had begun with handing out white feathers and shaming men into enlisting. After the War, many of these men would not come home; others would never recover; others struggled with their traumatic experiences. The aggression and the enthusiasm “immodestly” displayed by women during the war when handing out white feathers was channeled into factory jobs and into college classrooms. One could argue that the generation of men who fought the war lost their place and women suddenly managed to find a purpose for their new lives.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.