The Brief Existence of Constructivism

At the Paris Fair of 1925

The International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts was “international,” stressing the nationalism of the post-war period, but the French, the host nation, proved to be cautious with which countries were invited and included. The French government had officially recognized the new Soviet Union in 1924, so the invitation to the Exposition was belated, but the artists sprang into action. Along with Le Corbusier’s Pavilion de l’Esprit Nouveau, the Soviet Pavilion stood out as the two buildings resisting the blandishments of Art Deco and memories of early pre-war modern architecture. Only in these two buildings was the Bauhaus spirit manifested and only in these two buildings was ornamentation and decoration resisted for an assertion of the philosophy of Construction as Design. The Soviet Pavilion, which exists today only as a series of photographs, was a series of slices of architecture composed of slants and diagonals. The Pavilion was daring and simple: two triangular volumes sliced in half by a staircase. A glazed wall, windows stretching from roof to road, bend steeply to make way for a rising flight of steps. From the outside one could look through this sheet of glass and view all the exhibitions inside the building. Above the stairway, the series of diagonals crossed like swords above the processional also functioned like a faux set of roof beams supporting nothing, existing only as formal shapes. This stunning building turned the architect, Konstantin Melnikov (1890-1974) into a sought-after celebrity among the Parisians. Only Le Corbusier, a Swiss architect, working and practicing in Paris, had offered such an architectural work of such revolutionary impact. Perhaps because he was representing a far-away and still unfamiliar government, Melnikov’s offering was better received than that of Le Corbusier whose threat to the status quo in France was far more apparent.

Soviet Pavilion at the World’s Fair, Paris 1925

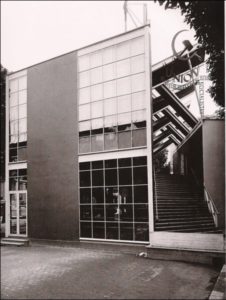

The best analogy to this building would be the contemporary design for the Wexner Center of the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, designed in the late 1980s by Peter Eisenmann. Eisenman took his abstract philosophical theories of deconstruction as applied to architecture and refused the architectural dictates of straight lines and enclosure for broken angles and opened walls.

The Wexner Center of the Arts

But Melnikov was using abstract two-dimensional shapes from painting as architectural slabs fitted together into a dynamic and daring pavilion. However, Melnikov’s working method revealed a deconstructive mindset, for his preparatory drawings showed that he played with geometric shapes which he broke up and reconnected through causal intersections. Indeed, much of the building was glass, buttressed by an occasional slab wall here and there. Topping the building was a tower of open work trusses, suggesting the Tribune of El Lissitzky. The skeletal projection was also a flag pole, and it should be noted, that, at the closing of the Exposition, the flags of all nations were ceremoniously lowered, except for that of Russia. For days afterward, the red flag with the gold hammer and sickle rode the late summer breezes. Clearly, Melnikov was experimenting with the language of architecture, as was Eisenman, almost one hundred years later, deconstructing the concept of “structure” in what was probably an experiment in formal language. Even Le Corbusier’s offering was conservative compared to the Russian architect’s design that was as savage and brutal as it was a fragile accumulation of teetering walls, leaning against each other. As if to emphasize the precariousness of the structure, a conglomeration of words suspended in air, somehow attached to the building, announced that this was the Soviet Pavilion. If anyone was in doubt, a hammer and sickle rose in the air, cutting into the sky. While he was in Paris, Melnikov gave an interview, recently translated, in which he laconically described his intentions:

This glazed box is not the fruit of an abstract idea. My starting point was real life; I had to deal with real circumstances. Above all, I worked with the site that was allocated to me, a site surrounded by trees: it was necessary that my little building should stand out clearly amidst the shapeless masses through its color, height, and skillful combination of forms. I wanted the pavilion to be as full of light and air as possible. That is my personal predilection, but I think it reasonably represents the aspiration of our whole nation. Not everyone who walks past the pavilion will go inside it. But each of them will see something of what’s exhibited inside my building all the same, thanks to the glazed walls, and thanks to the staircase that goes out to meet the crowd, passes through the pavilion, and enables them to survey the whole of its content from above. As far as the intersecting diagonal planes over the route are concerned, may they be a disappointment to lovers of roofs corked up like bottles! But this roof is no worse than any other: it is made so as to let in the air, and you keep out of the rain from whatever direction it may fall.

The Soviet Pavilion, with its interior exhibits, was a container that was a Constructivist “thing” or object that, in turn, held more “objects” from the utopian society. And yet, Melnikov’s design intention was never symbolic. He was concerned with the site itself only—where the building was located at the fair and the fact that the exposition was a temporary event, destined to be torn down. As the result of accepting the ephemeral nature of the placement, there is a thrown-together-soon-to-be-demolished temporary air of casualness about the Pavilion that reinforces the artist’s statement: “..why should a building whose function is temporary be granted the false attributes of the everlasting? My pavilion doesn’t have to keep standing for the whole life of the Soviet Union. It’s quite enough for it to keep standing until this exhibition closes. To put it briefly, the clarity of color, simplicity of line, and abundance of light and air that characterize this pavilion (whose unusual features you may like or dislike according to taste) have a similarity to the country I come from. But do not think, for goodness sake, that I set out to build a symbol.”

The Temporary Soviet Pavilion in 1925

In addition, as with the displayed objects inside, the object/structure was an example of faktura or the practicality of industrial materials used as materials without disguise or cladding or decoration. Glass was glass, steel was steel and wood was wood. However, although the architect intended the building to be read as an independent Constructivist object in its own right, the Pavilion was understood by others as a propaganda document, advertising the modernity of the USSR, a newly arrived political entity, which, by ingesting European modernism, had forged forward on its own unique path. Inside the Pavilion, the Monument to the Third International by Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953) rose toward the ceiling, pointing to the sky and to the future of the Soviet Union. Alexander Rodchenko’s Workers’ Club, which served as an interior room and exhibit and as an object all at the same time, followed the utilitarian and ideological philosophy that an experimental construction or an example of how studio “laboratory” work could become a practical object. An abstract sculpture could become a building, an abstract painting could become a pavilion, and faktura could be mobilized to build simple and useful tools for the workers to use. The Club, which is an ideal model, was conceived by Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956) as a three-dimensional design for education and comradeship among workers. There is an exchange between the workers’ bodies and the activities practiced in the space: the long table is a communal affair, a place where workers congregate on both sides, facing each other. The worker is contained in an enveloping chair that curves around in a semi-circle, embracing him or her with the arms of comradeship.

Reconstruction of Rodchenko’s Workers’ Club

Rodchenko imagined these Constructivist objects to be comrades in their own right: friends and allies for the workers, working in unison with the laborers. Unlike the rather rigid and uncomfortable chairs, the tabletop could be altered. The top could flip up for writing or down for reading, but based on the photographs and reconstructions of this table, such alterations would have to be communal, at least on that side—everyone must read or everyone must write. And there are racks for magazines full of educational materials for the edification of the labor force. In describing these structures, Stepanova referred to them as “wall newspapers,” which like all the objects in the Club could be manipulated and controlled by the worker seeking knowledge. While newspapers dangle like towels from a white rack, Lenin peers down benignly from a photograph a year after his death. This is the “Lenin corner” with the photograph of the recently deceased and embalmed leader taking the place of the religious icon in the traditional Russian home. The corner is carefully designed, from the white square left blank, waiting for the requisite photograph, to the timeline constructed of a series of arrows. This corner was conceived of as more than a cult site where the worker was expected to peruse the archive of materials on Lenin that would, over time, accumulate as the heritage of the leader grew in Russia. In the place of religion, there was the cult of Lenin, who became the founding father about which all should learn and from whom all would be inspired. Rodchenko preferred the authentic record of Lenin, that is the many photographs taken of him to traditional portraiture. Lenin was modern, like the workers’ club and he was present, not in representation but in a substitute reality, hovering in the index of the camera’s record of his existence.

True to the desire to educate the worker, there is a speaker’s lectern and a movie screen, allowing the club to be turned into a site of saturation, where Communist philosophy could be absorbed by the now passive audience. As with his posters, Rodchenko demanded that the workers participate with and manipulate the media stands in order to obtain the information contained in the various stands. Above the heads of the activated workers, electric lights hang, symbolizing the goals of Lenin–to electrify and thus to modernize the nation and the desire to educate the people in the ways of Communism. There is an air of efficiency, from the simple and inexpensive materials used for the furnishings to the sense that the Club was completely transportable and could be set up in any available room. Time was precious and could not be wasted with fun and must be used for edification, put to good use in this Club that has everything but relaxation and enjoyment. The placement of the Club inside the Soviet Pavilion, suggesting an alternative to capitalism, in the City of Light, Paris. In Paris, one wasted time and sat at a sidewalk table and sipped a café au lait while chatting with friends and watching the parade of fashion down the boulevard. Such capitalist customs were a scandal to Rodchenko who was in Paris for the first and last time in his life. The contrast between the austerity and discomfort of the rigidly designed Workers’ Club and the long lunches enjoyed by Parisians could not be clearer: the Club was the Soviet rejection of Western decadence. It is impossible to miss the artist’s assertion of totalitarian control over the lower classes, their minds, their activities, their movements, and their time. The difference between the Leninist avant-garde and the Stalinist Socialist Realism is a distinction without a difference. It is clear, that, while the Workers’ Club was ostensibly a site of relaxation, complete with chess sets, this room was also a site of propaganda and control.

Writing about the Pavilion a few years after the Fair in the 1929 book, The Reconstruction of Architecture in the USSR, the artist El Lissitzky (1890-1941) said,

The first small building that gave clear evidence of the reconstruction of our architecture was the Soviet Pavilion at the Paris World’s Fair of 1925, designed by Melnikov. The close proximity of the Soviet Pavilion to other creations of international architecture revealed in the most glaring way the fundamentally different attitudes and concepts embodied in Soviet architecture. This work represents the “formalistic” [Rationalist] wing of the radical front of our architecture, a group whose primary aim was to work out a fitting architectural concept for each utilitarian task. In this case, the basic concept represents an attempt to loosen up the overall volume by exposing the staircase. In the plan, the axis of symmetry is established on the diagonal, and all other elements are rotated by 180 ̊. Hence, the whole has been transposed from ordinary symmetry at rest into symmetry in motion. The tower element has been transformed into an open system of pylons. The structure is built honestly of wood, but instead of relying on traditional Russian log construction [it] employs modern wood construction methods. The whole is transparent. Unbroken colors. Therefore no false monumentality. A new spirit.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.