Creating a Modern Visual Vocabulary of War

Part Two

The Great War caught everyone by surprise. The avant-garde movement, once international, was shattered and artists were scattered across Europe. Some were killed, some went into exile, others found neutral territory where they waited, but, regardless of whether one served, as with Georges Braque, or whether one waited, as with Sonia and Robert Delaunay in Spain, for the war to end, all in the art world saw a unique experiment in vanguard art come to an end. But the War had an interesting impact upon avant-garde art itself. This War, so technologically omnipresent, so mechanistically terrifying, and so insistently modern and strange in the annals of warfare, called out for an artistic style to express the horrors of the new century. Lingering realism seemed too dated, nostalgic Impressionism was inadequate, and Fauvism would have been simply unseemly. Cubism and Futurism presented themselves as stylistic candidates–extremes of the avant-garde–now suddenly and tragically appropriate to explaining the ravages and destruction of what it meant to die by machine in the twentieth century.

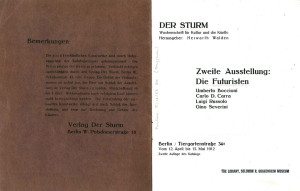

A year before the War began, the Berlin Secession, a venerable body by fall of 1913, held a salon, modeled after the Parisian Salon d’Automne, the Herbstsalon. Naturally Herwarth Walden, director of Der Stürm Galerie and organizer of all things avant-garde, sponsored the Salon in order to “present a survey of the creative art of all countries.” To ensure that the exhibition was sufficiently cutting edge, Walden curated the art, drawing from fifteen nations, creating what Peter Selz in his classic German Expressionist Painting (1957) called “the last of the significant international exhibitions of contemporary art held in Germany before World War I.” Many of the Salon Cubists were represented, most of the Futurist were out in full force as were their Russian counterparts, Goncharov and Larionoff, and the Blue Rider artists were all brought together with some Americans, including Berlin resident Marsden Hartley (1877-1943). Selz pointed particularly to Franz Marc (1880-1916), who submitted “Two more explicitly troubled paintings..” Selz continued,

Fate of the Beasts (1913) perhaps also related to the prevailing apprehensions of war, portrays a total, inescapable catastrophe..Marc when receiving a reproduction of Fate of the Beasts during the war in 1915, expressed astonishment at his own sense of approaching ruin..I was greatly stuck and excited at its sight. It is like a premonition this war, horrible and stirring; I can hardly conceive that I painted this?..A similar cataclysm prevails in The Unhappy Tyrol..Marc continued, The closer the time of the outbreak of the Great War approached, the ore clearly the work of the most aware artists reveals a breaking and bursting of form, a calamity of content. Some people believe that the threatening tempest announced itself to awakened souls; one face is evident is such creations: the European spirit had trend from innocent and naïve hedonism to a dark anguish and often helplessness before the horrible event occurred.

This 1913 image, also entitled, Animal Destinies (The Trees Show their Rings, the Animals their Veins), of an all consuming apocaplyse engulfing animals showed the impact of Futurism in the 1912 show and probably of the Secession exhibition in which Marc participated. Just a year earlier, Marc’s 1912 painting of Cows, Red, Green, Yellow is flush with frolicking happiness. In contrast, a year later, the painting of 1914, Birds, was less prophetic than Animal Destinies but strongly indicative of the impact of Futurism upon the rolling curves which had once embraced the peaceful bucolic animals innocent of conflict. By 1913, the feeling of impending disaster was strong. Marc’s associate Vassily Kandinsky explained to his collector, the American Arthur Jerome Eddy, that the presence of cannons in his painting, Improvisation No. 30 (Cannons) (1913) “could probably be explained by the constant war talk that has been going on throughout the year.” Sadly when Marc was killed in the very war both of the two artists foresaw, Kandinsky refused to carry on with the Blaue Reiter Almanac, saying, “The Blaue Reiter – that was the two of us: Franz Marc and myself. My friend is dead, and I do not want to continue alone.” Of course, in 1916 the statement of sorrow was academic: Kandinsky had been sent from Germany as soon as the War began and the Blue Rider was no more.

The moment of Futurism in Germany was brief. The War sent the Futurists back to Italy, where they watched the conflict that was to end the past and usher in the future–a conflagration they had so wanted–fought by other countries. Courted by both sides, Italy would not enter the Great War until 1916 and participated only in limited spheres deemed in the nation’s interests. Meanwhile, the very nation that had not wanted war, Great Britain, was dragged across the Channel into France, where it would leave an entire generation in the fields of Flanders. Thus ironically, it would be English, not Futurist artists, who would make the case that the new language of the avant-garde, a combination of Cubism and Futurism, was the most graphic linguistic means to convey the first modern war in Europe. It is through the war paintings of a group of artists who fall between the cracks of history–war artists, war painters–who made Cubism legible and allowed Futurism to take up the subject of destruction: war–“the only hygiene of the world.”

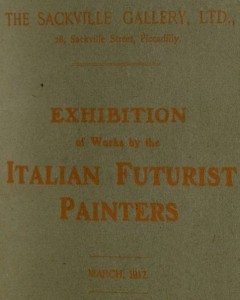

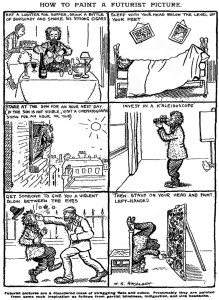

After a chilly and parochial visit to Paris, the Futurists left the Cubist quarrel behind and arrived in London in time for an early and equally chilly spring. Their groundbreaking exhibition was held, not at an avant-garde gallery, but at an establishment bulwark, the Sackville Gallery, Ltd, the “Ltd” being the operative term. The conservative and commercial nature of this establishment was in sharp contrast to the site of the controversial show, Manet and the Post-Impressionists, only two years earlier, mounted by Roger Fry at the Grafton Galleries. And yet this is the site which introduced the rowdy and earnest Futurists to the London public, an art audience ill-disposed towards the new. As Barbara Pezzini posted out in “The 1912 Futurist Exhibition at the Sackville Gallery, London: an Avant-Garde Show within the Old-Master Trade,” the London press generally speaking skipped over the political content and the radical messages in the paintings and made fun of the radical paintings. But as with the Bernheim-Jeune Galerie, the paintings were for sale, as Pezzini noted: “The Futurists had sonorously proclaimed their contempt for commerce, especially for the old-masters trade, and yet they exhibited in private galleries” and in fact, “most of the works exhibited in London were bought in Berlin by the banker Wolfgang Borchard, who attempted to take over the touring exhibition.” The Sackville, as its name suggests, handled old masters and its entire atmosphere of connoisseurs contemplating priceless objects made the mere mention of money vulgar.

Not surprisingly, the Futurist exhibition was a one-off for this gallery. The shocked Times of London fulminated, “The anarchical extravagance of the Futurists must deprive the movement of the sympathy of all reasonable men.” But the show was advertised in terms of sensationalism, a spectacle made for high-brow amusement. As has been seen, the Futurists had little control over their venues and over how their art was bought and sold. In fact, according to Pezzini, “The ‘sensational’ Futurist exhibition can be interpreted as part of a marketing strategy by the Sackville Gallery directors to attract ticket-paying customers to their establishment, not only to profit from their entry fees, but also with the aim of selling to them more profitable pictures and objets d’art.” That said, the Futurists, through the commanding and flamboyant presence of Marinetti and their catalogue, could attempt to communicate with their British public. The text of the catalogue, on sale for sixpence, a compendium of manifestos titled, “The Exhibitors to the Public” was translated for each venue, from Italian to French to English to German. That said, the aim of galleries such as the Sackville was not to sell art but to sell tickets. As Pezzini explained,

Even if the Futurists gained financially little from the experience, their exhibition did contribute to the display of an alternative kind of art to that usually seen in such spaces. Avant-garde exhibitions not only became of significant importance in the British art world, but their success with the public contributed to the creation of specific venues for the showing of modern art after the First World War..The bourgeoisie might laugh, but other forces were listening.

Indeed, more than any other artists, it was the British who were the most receptive to the Futurists. The reasons for the closed minds of the London and the open minds of the artists were the same: England had a native tradition, the Pre-Raphaelites and their many followers, but however beloved the paintings of English history, they were out of date, out of step with the times. In fact, as early as 1910 at the Lyceum Club in London, the titular leader of Futurism, Filippo Tomasso Marinetti criticized John Ruskin,the long dead art critic, who still had a hold on the English artistic imagination, stating “Your deplorable Ruskin…with his sick dreams of a primitive pastoral life..” The artists recognized in Futurism its involvement with the present, and it must be pointed out that the radical message of class revolution and overthrow of the old world would have found fertile ground in class-bound Britain before the War. The catalogue opened with Marinetti’s 1909 Manifesto, followed by the statement of the artists, Boccioni, Carrà, Balla and Serverini: “We go our way,” they wrote,

destroying each day in ourselves and in our pictures the realistic forms and the obvious details which have served us to construct a bridge of understanding between ourselves and the public. In order that the crowd may enjoy our marvelous spiritual world, of which it is ignorant, we give it the material sensation of that world.

Translations of the other Futurist manifestos and writings were not available in English, but the extremely revolutionary Futurist poems by Marinetti and other Futurist writers appeared in the journal, Poetry and Drama, where they would be read by D. H. Lawrence. The 1912 exhibition in London, while the most famous, was by no means the last. The Futurists returned a year later in April of 1913 and in May and June of 1914, a few months before the War broke out and Marinetti himself lectured to London audiences in French in 1910, 1912, 1913 and 1914. The fact that the poet did not speak English was a problem, and according to Andrew Harrison in D.H. Lawrence and Italian Futurism: A Study of Influence (2003),

The language barrier was a cause of the general ignorance concerning Futurism’s specific project for the arts. There was only one acknowledged English Futurist, C. R. W. Nevinson, who co-signed with Marinetti the new Futurist Manifesto entitled “Vital English Art” in the Observer for 7 June 1914. The general tendency among Marinetti’s more sympathetic English commentators was to assimilate his popularized anti-tradition declarations for their own purposes.

However, there were those who joined forces with the Italians for their 1913 exhibition at the Doré Gallery. Walter Sickert and Percy Wyndham Lewis, Edward Wadsworth, and Frederick Etchells showed with the Futurists in “The Post-Impressionist and Futurist Exhibition.” Perhaps the most important of the group was Christopher Nevinson (1889-1946), who along with Wadsworth and Lewis, would combine Cubism and Futurism with a native understanding of the Industrial Revolution, an English invention, after all, to create a new language for war. On the eve of the War, Nevinson, who could read Italian, and Marinetti held a conference in London in conjunction with a new Futurist exhibition at the Doré Gallery. This was an exhibition far more substantial than the Sackville show, presenting eighty works by the painters and leading theorists, Boccioni, Balla, Carrá, the writer and painter, Ardent Soffici (1879-1964), and the musician and artist, Russolo.

The close affiliation between Nevinson and Marinetti who performed experimental poetry readings led to “A Futurist Manifesto: Vital English Art.” One cannot imagine French artists beating drums with Futurist poets. However, the other artists, who, according to Teresa Prudente of The Modernist Journals Project, were not pleased with “Nevinson’s improper use of their signatures, by dissociating themselves from the Futurist Manifesto and by stating their independent position as an experimental group. The event started a process of internal division within the English avant-garde movement,” resulting in the formation of a new movement, independent of Italian Futurism, English Vorticism. Vorticism would have an unanticipated fate: it would become the visual symbol of England at war.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.