French Artists at the World’s Fair

The Last of Cubism, Part One

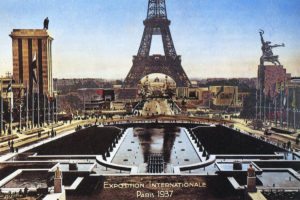

In 1929, the French Chamber of Deputies, fresh off their success with the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts of 1925 decided to repeat the fair in a decade. However, by 1936, the world had changed, stalked by a lingering and seemingly surmountable Depression and haunted by Fascism, so that the theme of decorative art seemed inappropriate. After much debate and a year’s delay, the vague theme of “art and technology” was selected. The Bauhaus had been closed in 1933, and, with its demise, the union between the two seemed to end and now art and technology were separated. When the International Exposition of Arts and Technics in Modern Life opened in May of 1937, it was very close to the end of the world. The year 1937 was studded with portents for the dark future that diplomats were struggling to stave off. When Franklin Roosevelt was inaugurated in January, he acknowledged the death grip of the stubborn Depression by stating that fully one-third of America was “ill-housed, ill-clad, and ill-nourished.” A few days later, in a similar vein, Heinrich Himmler reported that 8000 prisoners were in camps for political dissidents all over Germany. And at the end of January, Hitler announced that Germany was withdrawing from the Treaty of Versailles and all of its demands, and in April he said that if a nation was of one mind then all it needed was one political party.

Fascism was on the march. In Spain, the forces of General Francisco Franco were inflated by the air forces of Germany and Italy, which, as a practice run for engagements to come, put Operation Rügen in motion and bombed Guernica on April 26. They would be joined the next month by German Condor Legion Fighter Group, arriving for the coup de gras to the Republic. The day before on the 6th of May, the airship, the Hindenburg, blew up at Lakehurst, New Jersey. In the summer, Japan invaded China and in Germany, the Nazis put on one of the last large art exhibitions, one for “German art” and one for “Degenerate Art.” The rest of the year was dominated by the long and brutal war between the Japanese and the Chinese, culminating in the Rape of Nanking on December 13. By the time the fair closed, its purpose rang hollow and ironic: “The objective is to be a meeting place for harmony and peace by not only striving to promote economic exchange between peoples but also the exchange of ideas and friendship.”

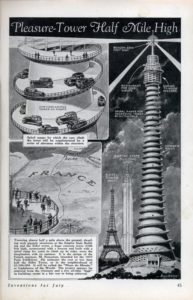

Meanwhile, in Paris, the city had to pretend that Spain was joined the pantheon of Fascism, uniting with Germany and Italy, Nazis and Blackshirts, and had to turn away from China being beaten to its knees by the ascendant Japanese Empire. The year 1937 was supposed to be a celebration of technological advances since the famously modern Exposition Universelle in 1889. Gustave Eiffel had explained that his famous tower, built for the occasion, symbolized “not only the art of the modern engineer, but also the century of Industry and Science in which we are living, and for which the way was prepared by the great scientific movement of the eighteenth century and by the Revolution of 1789, to which this monument will be built as an expression of France’s gratitude.” The long title that was given in 1937, “The Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne,” did not mean to be ironic, but everywhere new battleships were being commissioned and modern bi-planes were practicing bombing runs, suggesting the victory of technology given over to war. The French authorities put forward a serious plan to erect a new tower, called the Phare du Monde or, the optimistically titled, Lighthouse of the World, which was to be twice as tall as the Eiffel Tower. Despite its name, this lighthouse was dedicated to the automotive industry in France and apparently one could drive up a spiral road winding around this concrete structure to the restaurant on top. Not surprisingly, the building was not completed. However, other national pavilions were finished on schedule and bristled with political messages.

Pablo Picasso. Guernica (1937)

The Spanish Pavilion, one of the last acts of the Republican government and the first and only pavilion the Spanish Republic would have in a world’s fair, was designed by Josep Lluís Sert who asked his friends, Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró and Alexander Calder to decorate the interior. The pavilion opened seven weeks late and was not on the official map and few paid any attention to the important work of art inside. Picasso’s response to the bombing of Guernica is the best-remembered work of art for the entire world’s fair that year. But at the time, few understood the significance of the mural, Guernica, and the government was disappointed at the offering. The Reaper, a mural executed in situ by Miró, is forgotten perhaps because it disappeared on the way home to Valencia. Along with his red mobile, symbolizing the Republic, Calder’s Mercury Fountain, which pumped mercury survived and can be seen–behind protective glass–in Barcelona. Writing in Cahiers d’Art, defended Picasso’s painting: “These visionary forms have an evocative power greater than shapes drawn with every realistic detail. They challenge people to truly comprehend the effects of their actions.”

And then there were the Soviet and German pavilions, staring at each other across the Jardins du Trocadéro: two truly horrible erections of totalitarian architectural madness, predicting horrors to come. The architect, Albert Speer predicted, “Our architectural works should also speak to the conscience of a future Germany centuries from now.” Somehow Speer had come across the secret plans of the Soviet architect, Boris Iofan, and, when he realized the possible impact of Vera Mukhina’s Worker and Kolkhoz Woman, he countered with an eagle surmounting a swastika topping his edifice. In an article on these dueling buildings, Paul Garson remarked that the German intelligence service had interpreted the Soviet sculptures as “symbolizing a Soviet invasion of Germany.” In his March 2017 article.”Clash of Ideology at the Paris Expo,” Garson continued, “Both building designs were also windowless, with no light either entering or escaping, the visitors sealed within and subject to whatever sounds and sights awaited them. Both pavilions appeared sepulchral in form and atmosphere, although not so intended by their designers, at least consciously.” Today, it seems impossible that such blatantly officious buildings were ever imagined, much less built, but ample film footage of the event, including shots of these architectural monstrosities, exists today. I stress the aggression of the twin totalitarian towers for two reasons: first, it would be Mukhina’s ordinary men and women who would eventually defeat an empty ideology, symbolized by Speer. And the second reason for emphasis would be the work of French artists in the French pavilions, all of which speak in a different voice, one of hope and optimism, bright colors and jaunty designs. And these works of art can be seen, with hindsight, as a picture of a nation that has its head in the sand–of a nation that will be no match for the relentless ambitions of the Nazis, who, in three years time, would march down the Avenue des Champs–Élysées. In 1937, the two buildings functioned as giant advertising billboards, selling two extremes of totalitarian solutions to the world’s problems—military might or a workers’ paradise. France, mired in anti-Semitism and class warfare combined with ideological rifts, was, like the Eiffel Tower, standing helplessly in the middle.

The French government was far less efficient in building its own structures, mainly because French workers did what French workers always do when faced with the opportunity to embarrass the ruling class–they went on strike. After years of class warfare–between 1934 and 1936 there were over one thousand demonstrations of some kind–the children and grandchildren of the Communards were slow to complete the commissioned structures. France had been torn between fascism and communism and the Third Republic attempted to find a middle path but the exposition as a whole became a site of nationalistic propaganda. Faced with the sophisticated forces of Germany and the Soviet Union, the host nation felt compelled to present “la Firme France.” The French contributions to their own exposition seem, in hindsight, naïve and doomed in their determined optimism.

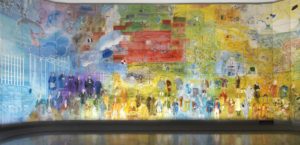

Raoul Dufy. La Fée Electricité or the Electricity Fairy at the Palace of Discovery (1937)

When electricity was introduced to the streets of Paris in those last delirious years before the Great War, the people were delighted and enchanted. Some twenty years, electricity was commonplace, lighting streets and powering vacuum cleaners. Raoul Dufy was given a formidable challenge when his sponsor, the Compagnie parisienne de Distribution d’Electricité, the company that organized all the electricity for the city, presented him with the concave back wall of the Palais de la Lumière et de l’Electricité, another building by the formidable architect, Robert Mallet-Stevens. A former Fauve artist whose specialty was charm, Dufy was the last artist to execute anything scientific and he retreated to the realms of enchantment and turned electricity into a delightful fairy tale. According to the Museum of Modern Art in Paris,

“..the story of The Electricity Fairy was based on De Rerum natura by Lucretius. In this composition measuring 10m x 60m, he works from right to left on two main themes, the history and applications of electricity, from the earliest observations right up to the most modern technical achievements. The upper part shows a changing landscape across which are dotted some of the painter’s favourite themes: yachts, flocks of birds, a threshing machine and a Bastille Day ball. Portraits of 110 great scientists and inventors who have contributed to the development of electricity are arranged across the lower half. Blending mythology and allegory with historical fact and technological description, Dufy plays on the contrast between opposites – the gods of Olympus in the centre of the work and the power plant generators linked by Zeus’s thunderbolts; primordial nature and architecture; works, days and modern machines. In formal terms also, hot colours contrast with cold, with the dominant colours being clearly differentiated by zone. This dual narrative thread is resolved in an apotheosis as Iris, the messenger of the gods and daughter of Electra flies through the light above an orchestra and the capital cities of the world disseminating all the colours of the spectrum.

And for those unfamiliar with the poem by Lucretius, On the Nature of Things, it begins:

Mother of Rome, delight of Gods and men,

Dear Venus that beneath the gliding stars

Makest to teem the many-voyaged main

And fruitful lands- for all of living things

Through thee alone are evermore conceived,

Through thee are risen to visit the great sun-

Before thee, Goddess, and thy coming on,

Flee stormy wind and massy cloud away,

For thee the daedal Earth bears scented flowers,

For thee waters of the unvexed deep

Smile, and the hollows of the serene sky

Glow with diffused radiance for thee!

In his book, Dreams of Peace and Freedom: Utopian Moments in the Twentieth Century, Jay Winter wrote that

This work of art may be the largest painting in history, measuring in total over 200 feet long and 32 feet high..Dufy accepted the challenge of producing it within a year. And this is precisely what he did, with the assistance of his brother Jean Dufy and André Robert. Dufy listened to scientists; visited workshops, generators, and factories; and then proceeded to paint 250 panels on the subject of electricity. These panels were assembled in a hanger in the Paris suburb of Saint Ouen and were produced with such efficiency that–unlike many other elements of the world’s fair—the ensemble actually was ready for the opening exhibition..Entering the pavilion, the visitors came upon a 20 foot long electrical sparking current, joining two copper spirals; here was the longest continuous electrical current of its kind in the world. This gigantic display was only a prelude to what visitors saw at the heart of the building. Entering a huge hall painted black, they confronted Dufy’s mural on the “spirit of electricity,” a spectacularly colorful and illuminated mural. The majesty of science was there in all its splendor.

A sense of the vast scale of the mural can be seen in contemporary videos of the work, which is one of fantasy and escapism. Somehow, Dufy magically waved a wand and wished away the lurking militarism and the confrontational ideologies poised against each other elsewhere on the fair grounds. Naïve or willfully ignorant and disengaged or comforting in its evocations of fairies, the mural summed up the contradictions of Paris in the 1930s–looking backwards without looking inwards.

The discussion of the artists at the 1937 Fair continues in the next post.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.