Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp in New York

The Americanization of Dada, Part One

In an interview with Pierre Cabanne, decades after the Great War, Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) explained how he became an artist and how it was that he came to be exempted from military service–and the two events were linked together. In pre-war France, a nation anticipating a war with Germany, there was a “three year law,” which allowed a young man to do one year instead of three, if he fell under certain exemptions. Feeling, as he put it, “neither militaristic nor soldierly,” Duchamp stumbled upon the fact that there were exemptions for doctors and lawyers and, surprisingly, “art workers.” For the military, “art worker” meant someone skilled in typography or printing of engravings and etchings. It is at this point that Duchamp shamelessly cheated: his grandfather had been an engraver and had left behind some copperplates with “extraordinary views of old Rouen.” The grandson worked with a printer and learned how to print his grandfather’s plates and impressed the jury in the same city and Duchamp was classified as an “art worker.” However that promising start to his military career ended under the withering disapproval of his commanding officer and he was discharged and forever exempted. And so it was that Marcel Duchamp, discouraged by the emptiness of a sad Paris during the Great War was able to come to New York and find Dada there.

It is during that brief period of time, from 1915 to 1918, that Duchamp concentrated on a theme he inherited from the Futurists: the machine. In his introduction to The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, Michel Sanouillet explained,

Duchamp’s attempt to rethink the world rests on two supports, the machine, the image and incarnation of our epoch, and chance, which for our contemporaries has de facto replaced divinity. Towards 1910 he was in contact with futurist experiments and conceived the vision of a society where the automatic and artificial would regulate all our relationships. it was to better affirm his humanity that he integrated himself into this new world. He was going even beyond our own time, which still persists in wishing to adapt the machine to man. Duchamp was trying to imagine a state of affairs where man would humanize then machine to such as extend that the latter would truly come to life..What if the machine, stripped of all anthropomorphic attitudes, were to evolve in a world made in its image with no reference to the criteria governing man, its creator? What if, like Kafka’s monkey, it servilely imitated all human grimaces and gestures with the exclusive goal of freeing itself of its chains and of “leaving” them? Then, if the machine were to love, desire and marry, what would be its mental processes?..According to Duchamp, the machine is a supremely intelligent creature which evolves, in a world completely divorced from our own; it thinks; organizes this thought in coherent sentences, and following the technique describe above, uses words whose meaning is familiar to us. However, these words conspire to mystify us..On the other hand, what would happen if the machine admitted the possibility of accident, or non-repetition, exclusive attribute of man? Better yet, if having gotten ahead of us, it learned to use chance for utilitarian or aesthetic ends?

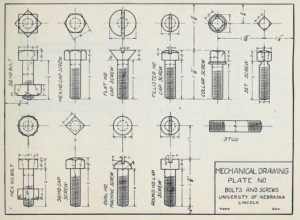

Mechanical drawing of Bolts and Screws

This rather long speculation on the machine owes more the contemporary science fiction than to the mindset of 1915, but there is no question that Duchamp and his friend Francis Picabia (François Marie Martinez Picabia)) though long and hard about machines as humans and considered the possibility that humans were also machines or mechanical in their operating systems. When Picabia returned to New York, he paused in his career as a painter for almost a decade and embraced on an interesting series of “mechanomorphs,” or portraits of those in the New York art scene as corresponding machines. In other words, if his friends were machines, what kind of machine would he or she be? It was, at this stage of his career , for Picabia to give up painting for it was a medium too “fat” and shiny and sensuous for the machine and its mechanical nature.

Francis Picabia. I See Again in Memory, My Dear Undine (1913)

Like the artists of New Objectivity who would emerge in a decade, Picabia turned to mechanical drawing, dry and circumspect, straightforward and pragmatic. The source material was plentiful and industrial designers and their drawings, artless and presentational, were available in catalogues and manuals. Mechanical drawing itself is an acquired skill, with the artist working at a drafting table with instruments such as compasses and straight edge rulers. It is an art or precision, designed to show and tell without introspection and without need of interpretation. Or course,

reading” these complex renderings is a skill in itself, but, for artists, the reading was less important than the emotionless rendering itself.

Francis Picabia

When Picabia returned to New York in 1915, his sponsor and colleague, Alfred Stieglitz, was in a bit of a holding pattern. A successful photographer, art dealer, sponsor of avant-garde in America, publisher of a major art journal, Camera Work, Stieglitz had been the main conduit for contemporary art but the Great War had stymied the free international exchange of ideas and art. Middle aged and in an unhappy marriage, the photographer faced a crossroads, and, indeed, in 1916 he would close 291 and end that chapter in his life. But, as always the older man surrounded himself with young protégées, in this case, the poet Paul Haviland and the poet Agnes Ernst Meyer, who convinced him to start a new and innovative art magazine, 291, after the famous gallery. Picabia eagerly joined this new enterprise and filled the pages of 291 with a series of “object portraits,” or mechanical drawings of notable members of his artistic circle, pictured as machines. This idea of a person as a metaphor would be copied a decade later by Charles Demuth who painted the poet William Carlos Williams as one of his own poems, I Saw the Figure Five in Gold. But Picabia was far more rigorous in both is approach and his drawing of these “portraits.” No painting is involved, a renunciation similar to that of Duchamp, who was also moving towards a mechanistic form of rendering, as seen in his linear recreation of one of his earlier paintings of a chocolate grinder on the cover of The Blind Man. Picabia explained later that it was his time in America inspired his turn to the machine:

This visit to America has brought about a complete revolution in my methods of work..Almost immediately upon coming to America it flashed on me that the genius of the modern world is machinery, and that through machinery art ought to find a most vivid expression. I have been profoundly impressed by the vast mechanical developments in America. The machine has become more than a mere adjunct of human life–perhaps the very soul.

Picabia was in and out of America between 1915 and 1917, before declaring his farewell to Dada in 1918. During this time of restless traveling, he was in Barcelona where he published a European version of 291, called 391, in which a number of his machine drawings appeared. Using industrial catalogues as a resource, Picabia seems to have favored cars and their many parts as his main source of inspiration. For a man as fascinated with cars as he was, it would not be surprising that he would not only know of manuals of parts but would also be familiar with the actual experience of being a mechanic. Early cars were temperamental and the owners were expected to be able to do their own repairs at a basic level. As Mariea Caudill Dennison explained in her interesting article, “Automobile Parts and Accessories in Picabia’s Machinist Works of 1915-17,”

His American residency gave him ample opportunity to browse in contemporary American printed material, finding illustrations and diagrams of auto parts in magazines, advertisements, handbooks, manuals and even window dis- plays..By the summer of 1915, combination starting, lighting and ignition systems were becoming increasingly common in cars, both as standard equipment and add-on packages.

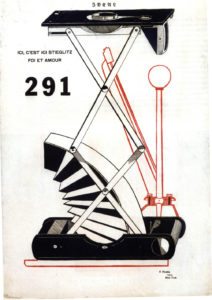

Francis Picabia. Ici, c’est ici Stieglitz /foi et amour (1915)

In one of the finest of these “portraits,” Alfred Stieglitz was, predictably, a camera or his exact camera to be precise, a vest pocket Kodak model. But Picabia added additional “equipment,” so to speak, a gearshift, which gives the car instruction, and a brake lever that perversely put the camera/car in an immobile position. The brake on Stieglitz has been interpreted as the stalemate the photographer faced as he was a decade past his breakthrough as a “straight photographer.” Both William Innes Homer and William Camfield assert that the brake should be thought of as the photographer at a creative standstill. Appearing on the cover of the July-August 1915 issue of 291, this crisp drawing indicates the speed with which Picabia, who arrived in New York in June, found his métier. As William Rozaitis descried the drawing in “The Joke at the Heart of Things: Francis Picabia’s Machine Drawings and the Little Magazine 291:”

The viewer is confronted with a crisply rendered machine. Its parts are easily identifiable as those of a camera: a lever and a handle appear to the right; a bellows puffs out of a film box at the bottom; and connected to the box by a series of overlapping, riveted supports is a lens. The drawing bears the inscription and title, Ici, c’est ici Stieglitz /foi et amour (Here, this is Stieglitz / faith and love), an apt description of the master photographer (1864-1949) who selflessly worked, with “faith and love,” to raise the status of photography to an art form and to introduce modern painting, drawing, sculpture, and photography to the American public. The word “ideal” appears in Gothic script above the camera’s lens, while 291-the title of the magazine as well as the name of Stieglitz’s well-known gallery-appears to the left, suggesting that the contents of the magazine will champion the same “ideal” standards for modern art that led inspired artists and devotees to crowd Stieglitz’s small room.

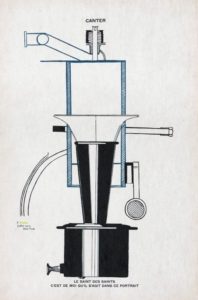

Francis Picabia. Le Saint des saints (1915)

The meanings of the suite of five “mechanomorphs” are as complex and personal as the drawings are simplified and impersonal. Picabia’s own self portrait, Le Saint des saints, is a braying automobile horn, also called a “canter,” by the artist, that is one who speaks “cant” or a local language. At the bottom, Picabia wrote “C’est de moi qu’il s’agin dans ce portrait,” which means: “The holy of the holies is to me that it is in this picture.” Le Saint des saints is a portrait of an artist as a conveyor of a message, but, as a prophet, he arrives in a fast car, a machine, the object of the future. If Picabia was a source of noise, then Paul Haviland was a portable electric lamp–a source of light. the poet was wealthy, representing Limoges china to American consumers, and was a financial backer of 291. The portrait, titled, La poésie est comme lui. Voilà Haviland, is a relative simple one, suggesting that Picabia was politely paying tribute to the man who was making his work possible.

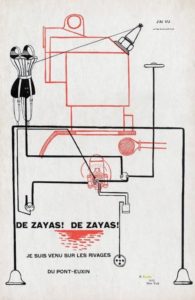

Francis Picabia. De Zayas! De Zayas! (1915)

If we overlook the curious fact that the cord for the lamp lacks a plug, in contrast, the rendering of Stieglitz was borderline insulting, if art historians are to be believed, and the portrait of the close associate of Stieglitz, Marius de Zayas (1880-1961), and their benefactor Agnes Ernst Meyer were also less than flattering. Much ink has been spilled on figuring out the many parts of De Zayas! De Zayas!, the portrait of De Zayas, the editor of 291. Indeed, it was De Zayas who had introduced the idea of Apollinaire’s petit revue to New York and published twelve issues of the magazine. He soon left the association with Stieglitz to open his own gallery, The Modern Gallery in 1915. Stieglitz, used to being the only game in town, objected to this sudden move towards independence and the two collaborators drifted apart. Perhaps as an acknowledgment of the estrangement, the gallery was renamed the De Zayas Gallery in 1919.

That said, in 1915, the object diagram of De Zayas is complex and undeciphered, part machine and part fashion illustration, complete with an old fashioned woman’s corset, with no woman in it. Homer noted that the inscriptions were equally strange: “J’ai vu/et c’est de toy qu’il s’agit,” or “I have seen you and it is you that this concerns.” Even more puzzling, the artist wrote, “Je suis venu sur les rivages/du Pont-Euxin,” or “I have come to the shores of Pont-Euxin.” As suggested by the presence of the empty corset, this portrait seems to have sexual content, from a male perspective. Indeed as Mariea Caudill Dennison remarked

Given Picabia’s inclination for linking women and sexuality with machines, it is no surprise to find a woman’s corset here..The female sphere in De Zayas! De Zayas! is clearly the black electrical schematic drawing. Picabia equated a female to a spark plug in Portrait of an American girl in a state of nudity (1915) and here the spark plug is linked by a diagonal line..This point of contact between the red and black systems in Picabia’s rendering suggests that the female creates a spark or surge of electricity that excites or activates the base of the connecting rod. In a car engine the connecting rod moves with the piston (not shown in Picabia’s work) up and down inside the cylinder. The plunging movement within the cylinder is analogous with sexual intercourse..Picabia has seen machinery and females as sources of art and has conquered them both.

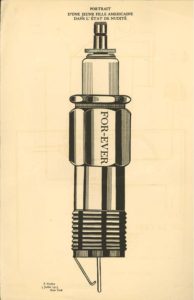

Francis Picabia. Portrait d’une jeune fille américane dans l’etat de nuditié (1915)

Next to the famous portrait of Stieglitz, it is the spark plug, perfectly copied in its simple entirety but titled Portrait d’une jeune fille américane dans l’etat de nuditié of 1915, that is the most well-known of the object portraits. Homer suggested, although others disagree, that the jeune fille was a portrait of Agnes Meyer, a married woman, with a wealthy husband. The money she was able to contribute to the “cause” of avant-garde made her a “spark plug” for the artists. As a patron, she made their engines go, sparking their progress. Engraved on the side of the spark plug was the word “Forever,” an ironic inscription, given that it was she who funded De Zayas’ gallery, considered a rival to Stieglitz. The “young girl” was copied from a very deluxe spark plug called a “red head,” but, viewing this homage from the vantage point of one hundred years later, the analogy between a mature married woman and a spark plug in the service of male artists is patronizing and condescending. However, the equation between women and machines and sex was one of the conceptual foundations of Picabia’s work of this interim period. In Picturing Science, Producing Art, Peter Galison noted,

Here we get to the heart of the matter, or rather, the sex of the machine. Surely the spark plug is a phallic woman (which is to say a metaphoric hermaphrodite). Yet she is rendered quite explicitly unthreatening by her very “nudity” and controllability–by our recognition that she stands naked of the larger apparatus that controls her sparking. .PIcabia’s vision of the plug’s erotic potential is suggested by is statement that he chose the spark plug for his girl because she was the “kindler of the flame.”

Sadly, shortly after this remarkable series of machine portraits or mechanomorphs, Picabia had a mental and physical breakdown and in 1916 left New York for Barcelona where he produced a new magazine, 391, nihilistic and alienated and aggressive. Reflective of the personality of Picabia himself, the issues also presented some of his ”portraits mécaniques.” In the third issue, Marie, a fan belt represented the artist Marie Laurencin, who was associated with Apollinaire. Then in 1917, Picabia returned to New York and continued his publication. Subsequent studies of the work of this artist during the years of the War have been somewhat sloppy in assuming his art was a critique of the New Woman or the Flapper, but these liberated women asserted themselves only after the war was over, and in America at peace, women were safely in their traditional places. There is no evidence to suggest that the Spanish-French artist was aware of the Suffragette movement, taking place in front of the White House in Washington D. C. Both Picabia and Duchamp had complex and varied experiences with many women and these events often found their way into their art in what David Hopkins called “male self-referentialty.” It seems more likely that, like Duchamp, Picabia’s interest was less in women and their social position and more in the mechanics of sex itself–Stieglitz is old and impotent and women, as sex machines, exist for the pleasure of the young male, also a sex machine.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.