Dada Émigrés in Exile

The Disintegration of Kultur, Part One

On the one hundredth centenary of Dada, the gesture and the non-movement, distance and time has allowed for a new examination of what is are a conglomeration of confusing and contradictory groups of dissident artists. As has been pointed out earlier, Marcel Duchamp may have been labeled “dada” but his “dada” is a very particular anti-art proposition. In addition, there is a difference between the disengaged Duchamp of Paris before the Great War and the engaged and activated Duchamp in New York in 1917, followed by the famously indifferent Duchamp of Paris after the War. There are Dada offshoots, the founding fathers and mothers of Dada in Zürich, the Paris group which dissolved into Surrealism, the merz philosophy of Kurt Schwitters, and then there is the angry and political assaults of Berlin Dada in the post-war Weimar Republic. All of these manifestations are unique and distinct and each needs to be considered within its own historical context, rather than being dumped under a too large umbrella for convenience. Certainly some common traits seem to be shared among the movements, such as the use of “chance” that, along with “found objects” continues under Surrealism, and an anti-art stance. But these are ideas taken from Duchamp, who not only also stressed the significance of the thoughts, ideas and concepts of the artist over the skills and talents of the maker. Duchamp was essentially opposed to olfactory art or the art of good taste, attractive and sensuous art, and this stance was taken towards a very specific genre of art–the Parisian salons. That said, it was not he who introduced Dada to the Parisian avant-garde, it was Tristan Tzara, arriving after Duchamp had returned to New York.

Kurt Schnitters. Merz Collage (1920)

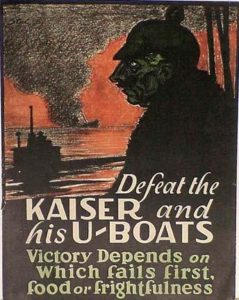

The arrival of Tzara in post-war Paris, was a signal that with the coming of the Great War the very nature of art changed within the avant-garde circles: the artists scattered to exile or to war, the galleries struggled to remain relevant, and the idea of art as a purposeless object projected intellectually and aesthetically to a select few was questioned by artists themselves. As the series on the art made during the Great War on this site has made clear, the normal artmaking apparatus was broken, and some artists sought a new role for art during the first modern war. And the War was where Dada cleaved apart. The French Dada artists, including Duchamp and his non-French associates, Francis Picabia and Man Ray, continued to be concerned with the avant-garde tradition, while the German artists rejected the avant-garde completely and sought something new. The reason for this schism rested in the situation in Germany itself during the Dada years. Germany was at war, as was France, but Germany labored under the burden of being the aggressor while denying the aggression which had started the War. From the very opening weeks of the War, Germany–as shall be seen–deliberately committed war crimes and lied about the actions of the military to their own people, setting up the German people for anger and disillusionment in peacetime. During the War itself, there was an intellectual struggle among European intellectuals for the “truth” of the German conduct of the War, a debate that brought German Kultur into disgrace, leaving an entire class of educated people without their social and political foundations. The year before Dada was founded in Zürich, Germany invented or initiated new forms of mass death, introducing them in the spring of 1915–submarine warfare against neutral nations, the aerial bombing of London, and poison gas was released on the battlefields to drift towards the trenches. By 1916, German speaking-people, their language, and their Kultur was under siege and discredited. They had committed atrocities and became the “Huns,” barbarians.

Propaganda Poster

Dada was founded in Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich when Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings opened the establishment to like minded exiles, fleeing from the War, in February of 1916. The name was “found” during a random leafing though a French-Germany dictionary by émigré artists in Switzerland. The dual language dictionary was indicative of the fact that a diverse international group of artists and writers from Germany and Romania and Alsace-Lorriane had washed up on the safe shores of neutral territory. Most of these artists were German speaking or came from territories dominated by German-speaking cultures, including Romanian Tristan Tzara from Romania, a new nation attached to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, but many, like Jean Arp and Tzara, spoke French. Despite their antics and experimental performance, the artists of Cabaret Voltaire were deeply intellectual and sought to re-create language itself. The selection of a nonsense word, “dada,” was deliberate and a signal that language itself would have to be interrogated. Therefore on April 18, Hugo Ball first used the new word, writing in his diary:

“Tzara keeps on worrying about the periodical. My proposal to call it ‘Dada’ is accepted. We could take turns at editing, and a general editorial staff could assign one member the job of election and layout for each issue. Dada is ‘yes, yes’ in Rumanian, ‘rocking horse’ and ‘hobbyhorse’ in French. For Germans it is a sign of foolish naïveté, joy in procreation, and preoccupation with the baby carriage.”

That a few discontented and alienated writers and artists in exile in a neutral city decided to run a cabaret of anti-art was not particularly important in the larger scheme of things during the war, but the presence of the artists who would later be called “dada” was symptomatic of a collapse of the German Kultur. For English speaking people, this term is often and incorrectly translated as “culture,” but that word is too broad. “Kultur” does not translate into English but can be explained to mean a production of literature, philosophy, poetry, science–the liberal arts of the educated classes–by the middle class. The university based education provided by schools that attracted students and scholars from around the world became the basis of Kultur, a uniquely middle class creation to counter the civilization of French culture which overlaid the courts of the German principalities. In Culture: The Anthropologists’ Account, Adam Kuper wrote, “The German not in of Bildung and Kultur, characteristically expressed in a spiritual idiom, engaged with the needs of the individual soul, valuing inner virtue above outward show, pessimistic about secular progress, are in turn imbued with the values of the Reformation and Thomas Mann suggested that the Reformation had immunized Germans against the ideas of the French Revolution.”

German Kultur Panel, Pitt Street, Leith

Even when Germany became a modern nation in 1870, the middle class had little role to play politically and all their energies were given the intellect, to a creation of a German, not French, Kultur that was private and inward. A valued and valuable national possession, Kultur was the pride of the German middle class that produced its concepts not through the language of international diplomacy, French, but with the German language itself, the language of home. By the Great War, the idea of Kultur being both under siege and superior to other European cultures and the justification of the War, as expressed by the German nation, was a defense of kultur, something worth fighting and dying for. As Hajo Holborn noted in A History of Modern Germany: 1840-1945,

The German propaganda had defined the ideological meaning of the war as the battle for the defense and victory of German Kultur over and against the Russian barbarism and autocracy in the East and the soulless civilization of the West. France, England and America had no Kultur but only a civilization characterized by its exclusive reliance on reason from which they had produced a mechanistic organization of society that forced the individual to conform strictly to its dull egalitarian standards..According to their own lights and tempers the authors described the nature of German Kultur differently and displayed lesser or greater contempt toward Western civilization. But the assertion that Germany had nothing in common with Europe and that the acceptance of Western ideas such as rationalism, liberalism, and democracy was a betrayal of Germany’s mission was monotonously repeated in the whole war literature.

Given its oppositional position, it is no surprise that kultur would become a weapon of war. As the Kaiser himself said, “Great ideals have become for us Germans a permanent possession, while other nations have lost them. The German nation is now the only people left with is called upon to protect, cultivate and promote these grand ideals.” The theme of the superiority of Kultur preceded the War and had become part of a fabric of self-belief for the average German. As Karl Wagner wrote in 1906, “War is the basis of all Kultur, of all morality. War is the source of all good growth. Without war the development of nations is impossible.” And in 1914, Karl A. Kuhn wrote The True Causes of the World-War, stating “Must Kultur rear its domes over mountains of corpses, oceans of tears, aunt eh death-rattle of the conquered? Yes, it must..” It is with this mindset of superiority that Germany marched to war, ostensively because of an assassination of an Austrian Archduke, and deliberately broke the neutrality of Belgium with the intention of invading France and with the assumption that the tiny nation was defenseless and would not impede their army on the way to Paris. The Germans entered Belgium territory on August 4, 1914, expecting capitulation but the Belgiums fought back fiercely, delaying the invasion of France, giving the Russians time to mobilize and the British the opportunity to join France and defend their ally. The Germans treated the Belgium people ruthlessly and brutally, committing atrocities and murders and massacres, not of the Belgium army but of civilian populations. Thousands died and thousands were rounded up and marched to Germany and placed in internment camps. The war against innocent people in small towns and villages horrified the rest of the world but the events that turned the Germans into “barbarians” were those perpetrated in the arena of culture in the name of Kultur.

August 1914

The next post will discuss these crimes against cultural property in Belgium and France and present the disintegration of the value of Kultur in the ashes of Louvain and Rheims as a backdrop to the Dada movement in Zurich and a reason for the famous “disgust” of Dada.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.