Timothy O’Sullivan: Exploring the West

Part Two

For decades the work of the nineteenth century photographer, Timothy O’Sullivan had been relegated to government archives and he was remembered, it at all, as one of the “operatives” of Matthew Brady and an assistant to Alexander Gardner during the American Civil War. Not until the 1930s was the full extent of O’Sullivan’s contribution to photography recognized and he was separated by the curator of photographer Beaumont Newhall at the Museum of Modern Art in New York from being a mere recorder of reality to the status of an “artist.” It is quite possible to discuss Alexander Gardner within the historical context of purpose driven photography without calling him an “artist” in the modern sense of the word. But to photographer Ansel Adams, who rediscovered O’Sullivan in an old album and to Newhall, O’Sullivan should be set apart from his fellow documenters and his work should be discussed in the context of art. The reasons for their conclusions were because, unlike his counterparts working in the American West, O’Sullivan had significantly deviated from standard compositional strategies and had apparently deliberately made what Adams consider “surrealist” versions of landscape. This new interpretation of a man, who was but one of many photographers hired to do a simple job, record new and alien landscapes for the federal patrons in Washington D. C. and for the taxpayers who were funding these scientific projects was perhaps anachronistic and re-placed the practice of O’Sullivan into an artistic context that may or may not have been appropriate. For decades a series of art historians have been debating the precise place of a body of work apparently resistant to placement.

The work of Timothy O’Sullivan could have been done, and in fact was done, by any number of individuals, young and strong and competent with a camera. After gaining experience in the American Civil War, the group of seasoned photographers, now based close to Washington D. C., shifted gears, as it were, to another more peaceful task: photographing the American West. Previous photographers, such as Carleton Watkins, had worked prolifically before the Civil War in order to advertise the pristine and unknown landscape in Yosemite. But the post-war photography had another role that involved exploration and scientific analysis of a new topography. Through the construction of scenic views, Watkins and his generation essentially tamed Yosemite by making the scenery familiar if inherently spectacular. But the American West was far from tame and far from familiar, even after the astonishment of Yosemite.

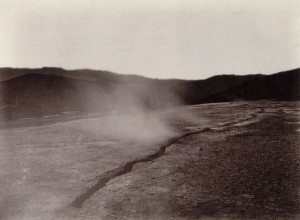

The inherent strangeness of the desert landscape, the towering mountains–true mountains–not the rolling green hills of the East, the volcanic grounds smoking and spewing, the surging and thrusting upheavals of rock from ocean bottoms were as alien as landscapes on Mars. To Eastern eyes, accustomed to leafy green trees and modestly rounded rock mounds and agricultural vistas verdant and drenched with spring rains, the startling sight of the vast and empty oceans of sand dunes, punctuated by strangely shaped spiked cacti and dangerous plunges of sheer cliffs were shocking and unexpected. And it should be noted that, in the end, when all the debates around Timothy O’Sullivan have subsided, it is the very novelty of this terrifyingly new landscape that probably challenged and intrigued him, perhaps even forcing him to create a new language to describe and explain new lands, entirely unsuited to conventional artistic responses.

Timothy O’Sullivan. Fissure Vent of Steamboat Springs

(1867)

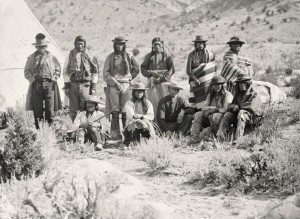

O’Sullivan, who seemed to have been a natural leader willing to take on responsibility, accompanied two survey exhibitions, one headed by Clarence King, a scientific survey headed by a civilian, and the other headed by Lieutenant George Wheeler, a military survey with a scientific goal. Both surveys, whether civilian or military, were corporate in nature, paving the way for settlements by cataloguing the resources available to the nation, all the while acting under the auspices of science. As a backdrop to this undramatic business was the doomed culture of the Native Americans, a panorama of tribes and a symphony of languages, some allied, some warring, all obstructing the technological progress signified by the locomotive, the “machine in the garden.” These endangered people were recorded and categorized with the same anthropological seriousness reserved for insect life. The mindsets of the participants in the survey parties probably reflected that of the majority of Americans. Even though a Civil War had just been fought on grounds of morality–slavery could not continue in an ethical nation–there was little empathy for the indigenous inhabitants, who had to be summarily removed to make way for the rapidly expanding ambitions of a maturing nation. Like his former colleagues, A. J. Russell and Alexander Gardner, O’Sullivan was a witness to another turning point in American history: the “winning” of the West. These documentary photographers were probably as sanguine as the other newcomers to the future of the region and assumed that the indigenous inhabitants would simply “vanish.” It is unlikely that O’Sullivan, hardened by a long war, would have wondered much about just where this vanishing point would be.

Timothy O’Sullivan. Pah-Ute (Paiute) Indian group, near Cedar, Utah (1872)

The photographic legacy of Timothy O’Sullivan is perhaps less interesting as evidence or as documents than the environmental conditions for the photographer himself. Faced with unprecedented un-European scenes in the unfamiliar Western territories, O’Sullivan had to find a way to photograph the land in such a way as to convey its inherent uncanniness. It is useful at this point to separate the images made by the survey photographer into non-chronological groupings, which would separate out records made of actual survey work, useful notations for the patron, the United States government, from the two predominate vantage points deployed by O’Sullivan–distanced and up close. In the process of making comparisons between landscape sites–then and now–separated by one hundred years, re-photographer, Rick Dingus discovered, apparently unexpectedly, that on occasion O’Sullivan had tilted his camera and, in the process, upended the spectator’s actual place on the scene and replacing it in the literal image with a skewed (and impossible) vantage point.

Timothy O’Sullivan and Rick Dingus.

Witches Rocks, Weber Valley, Utah, 1869 and 1978

The initial brief of the Rephotographic Survey Project was merely to photograph once again, following in the footsteps of the original photographers of the West, including O’Sullivan. On one hand, the modern photographer in 1977 could see the changes wrought by time; and, on the other hand, Dingus could learn more about the photographic practice of the early photographers. The idea that a photographer might select one vantage point over another would not be unexpected, but the entirely un-nineteenth century act of tilting the heavy wooden camera weighted down by a wet plate was something of a shock. There is no answer as to why O’Sullivan would do such a thing or how titling the composition as an option could have even occurred to him. Thanks to Rick Dingus we know that on occasion, Timothy O’Sullivan did something utterly outside of his own time. It seems highly unlikely that either Adams or Newhall would have known of this camera manipulation by O’Sullivan, but such extreme tilting was certainly worthy of the practice of New Vision Photography of the 1920s.

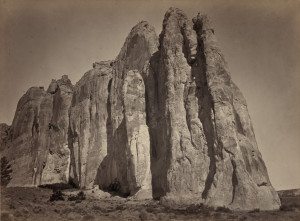

Timothy O’Sullivan. Inscription Rock, El Morro National Monument (1873)

While other of his photographs seem more conventional, but more often than not, O’Sullivan’s images proved to be unusual. Otherwise unremarkable images become, when rephotographed and compared by Dingus, remarkable. From Dingus, we learned that O’Sullivan photographed mountains from the full frontal position, with the face of the slope taking up all of the frame, leaving little background, cutting off the vistas that existed. The resulting images, lacking all but the most cursory foreground and a paucity of background or surrounding context, were not the result of cropping. Although the tilted camera technique was perhaps the most sensational, it is these frontal contemplations of rock faces, free of the expected repoussior or even middle ground reference, points that are the more striking, because they can be directly compared to conventional landscapes, both paintings and photographs of the nineteenth century. Dingus suggested that these odd angles and extreme close ups by O’Sullivan indicated that the photographer was either interested in or was attempting to provide evidence for the then current theory of catastrophe, that the earth was created, not in a uniform manner, but out of a series of catastrophic events which left behind evidence of geological upheavals. “Catastrophism” was the theory that drove the scientific approach of Clarence King on his survey of the West, a site he believed to have been the result of a series of catastrophes. The idea of a tilted camera mimicking a catastrophe is an intriguing one and may be a bit simplistic, but the mindset of the survey leader, Clarence King, is worth studying.

The third and last post on Timothy O’Sullivan continues the discussion on how his photographs can be viewed and understood.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.