(Not)Picturing the Slums

The London of the twentieth century imagination is based upon Merchant-Ivory film productions or Masterpiece Theater, or both. Here in these nostalgic realms, upper class life is recreated and evoked through elegant horse drawn carriages trotting past white row houses of the wealthy, jewel tone gowns and elegant tuxedos dancing at never-ending balls, spacious drawing rooms and book lined libraries, all bathed in the sepia tones, implying historical authenticity. What is conspicuously absent in these portrayals of the privileged is the overwhelming blanket of smells, the noxious stench that characterized modern London. Part of the appealing symphony of odors that wafted off the city, so powerful the scents travelled fifty or more miles, was the residue of unchecked industrialization. But there were other elements mixed into the aroma stew–human and animal waste, raw sewage and garbage–clouds of filthy fumes that presided over endless epidemics and parades of diseases, in other words, the fragrance of the poor, the unemployed, the left behinds, the left-outs, the left-overs, the unfortunates, better known as those who dwelled in the slums. While London and New York were similar in the refusal of those in power to remedy the conditions for those who lived in Seven Dials or St. Giles, for example, unlike the wealthy of New York, the rich of London did not live some distance away from the unfortunate immigrants and vagrants. Instead, a well-heeled English family in London could live back to back with back streets and back alleys, smell the smells without actually treading wading through the muck of despair and hopelessness. In fact, if the privileged classes of London had not been threatened by the constant cholera epidemics and revolted by the stench, little would have been done to improve, if nothing else, the sanitary conditions of the city.

As late as 1890, Punch published a cartoon about the “smells, smells, smells” and the “nasal misery” of London. And yet dramatizations of fin-de-siècle London fail to have characters mention the appalling living conditions. True, Sherlock Holmes used fog, which was really smog or reeking pollution, for dramatic effect, in The Forsyte Saga, a major character was fatally injured in a carriage accident caused by the shroud of unhealthy air, and Whitechapel, the killing grounds of Jack the Ripper, is familiar to any television audience. As the marvelous 2014 book by Lee Jackson, Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight Against Filth, recounts,London streets were coated with a mud thick with the dung and urine of the 100,000 horses of the city and blackened with soot, a mud that stuck to the shoes and the edges of long skirts. So terrifying was a walk on the streets of London that a new occupation, a street sweeper, sprang up. A young boy with a broom would appear and offer to sweep the detritus of the crossing, so that the fastidious could get from one sidewalk to the other without floundering in the mire.

William Firth. The Crossing Sweeper (1858)

But when Hollywood ventures into the Rookeries of London, the cinematic imagination machine grinds to a halt and reverts to the cosmetic and the picturesque of My Fair Lady (1964). It is possible that when George Bernard Shaw wrote the predecessor to the film, Pygmalion (1912), he did not realize that it was physically impossible to pass off a flower girl as a “lady,” because, due to poor nutrition, the poor were some four inches shorter than the rich. Shaw’s probable ignorance of poverty was typical of his time. Nineteenth century documentary of poverty was erratic, with writers, such as Henry Mayhew (1812-187) and Henry Mayhew (1812-187) , doing the better job of describing the conditions of the slums, embellishing the general horrors with human interest stories and opening appealing to the empathy of their readers. Whose heart would not be moved by the plaintive plea of abandoned child, Oliver Twist, “Please, sir, may I have some more?” As it turns out, the answer was—most people, who, like New Yorkers favored the explanation of Social Darwinism: survival of the fittest, and it you were poor, you were the author of your fate. Mayhew told other kind of stories, that of the city itself, the city and the River Thames, so filled with offal and dead bodies, it scarcely flowed. It sat and stank. As Mayhew wrote in September of 1849 in A Visit to the Cholera District of Bermondsey, the inhabitants near the river carried its poison in their bodies,

“The inhabitants themselves show in their faces the poisonous influence of the mephitic air they breathe. Either their skins are white, like parchment, telling of the impaired digestion, the languid circulation, and the coldness of the skin peculiar to persons suffering from chronic poisoning, or else their cheeks are flushed hectically, and their eyes are glassy, showing the wasting fever and general decline of the bodily functions. The brown, earthlike complexion of some, and their sunk eyes, with the dark areol~ round them, tell you that the sulphuretted hydrogen of the atmosphere in which they live has been absorbed into the blood; while others are remarkable for the watery eye exhibiting the increased secretion of tears so peculiar to those who are exposed to the exhalations of hydrosulphate of ammonia.”

It is against this backdrop that the picturing of poverty in the nineteenth century London, its slums and its people, needs to be understood. For an artist, for a photographer, there are obvious problems. First and foremost, for a professional and commercial visualizer, the only question is who will purchase my work? And this business quest for a target audience leads to the next question–what do people want to look at? The people of Henry Mayhew? Only Gustave Doré (1832-1883), a French illustrator, who was accused on inventing the sights he chronicled in London: A Pilgrimage (1868), did not flinch from entering into the heart of the maze of poverty and drawing what he found there. Doré and his pilgrimage into the hell of the slums is of particular interest because his book of engravings is contemporaneous with the documentary photography of John Thomson (1837-1921). In answering the question,what do people want to look at? Thomson answer was far more conventional and fit into the existing cultural horizon, not just of social expectations but also of political desires. Indeed, in his preface to his book Street Life in London (1877), Thomson took care to point out that photography produces “the unquestionable accuracy of this testimony ..will enable us to present true types of the London Poor and shield us from the accusation of either underrating or exaggerating individual peculiarities of appearance.”

The pertinent and inevitable comparisons of Thomson to Doré, an critical outsider, and to Jacob Riis in New York are both accurate and unfair at the same time. Doré’s work is perhaps the most compelling and unflinching of his time and Riis, like Doré, plunged directly into Mulberry Bend, the American equivalent of Whitechapel, and photographed the conditions and the people candidly without flinching. But Thomson followed another, already existing precedent, the tradition he had followed in China, that of what the French call petits métiers or street traders and vendors, considered the colorful “types” of any big city. This intention sets him apart from social reformers and places him in the preexisting practice of collecting and archiving only certain elements of the population–the dangerous classes, which needed to be monitored and studied. In the 2007 article “John Thomson’s London Photographs,” Lindsay Smith noted that Thomson was very aware of the earlier work of Henry Mayhew and of his use of photographs which were reproduced as engravings in his earlier books.

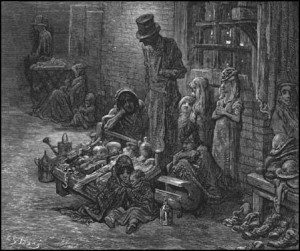

Gustave Dore. Houndsditch (1872)

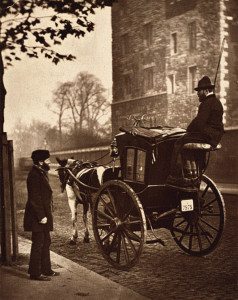

In New York, Jacob Riis was inspired by the examples of Dickens and Mayhew and Doré, but in London, John Thomson, fresh from his adventures in China, chose time-honored European prototypes for his study of Street Life in London. In producing this study of trades, which were presumed to coincide with human typology, Thomson did not work alone. He worked with Adolphe Smith (1846-1925), a journalist sometimes described as “radical” or “socialist,” who provided vivid texts to the photographs and, clearly, both men intended this book to be a kind of reportage about the individuals they found working in the largest city in the world. Indeed, this book is often referred to in terms of London “poverty” and even is placed within the context of the slums themselves. But, these individuals are not the “poor;” they are the hard working, masters of itinerate labor, skilled at specific tasks but adept at changing occupations as the weather or the customers demanded. As “authentic” as they supposedly were, these individuals were posed and photographed at the command of Thomson, pictured in a distancing and sanitizing manner, which separated the subjects from their customary lodgings and isolating them within the familiar framework of an encyclopedia of “types,” or the typical and colorful trades of the lower classes. The typological approach conceals the very real social problems that cause such precarious existences. In fact, to contemporary eyes, the very cover of their book signals codes of “quaintness” and a somewhat patronizing attitude towards the colorful street types who decorate London.

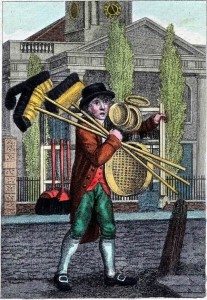

The semiotics that masked real social problems was typical of the genre and can be dated back to the eighteenth century prints of the “painter in water colours to Queen Charlotte,” William Marshall Craig, who showed the lives of itinerate workers in London. These workers, whose descendants would be photographed by Thomson a century later, would call out their services or name their wares in a chorus of shouts that were famous in London. Cries of London showed a tradition of street theater, characteristic of the city since the seventeenth century.

William Marshall Craig. “Hair Brooms.” Cries of London. Itinerant Traders of London in their Ordinary Costume with Notices of Remarkable Places given in the Background (1804)

In The Rise and Fall of Class in Britain (1999), David Cannadine explained that the British class system changed during the early years of the nineteenth century. A series of laws and reforms, especially after the passage of the Reform Act of 1835, served to consolidate the traditional historical power of the privileged aristocrats and the new financial power of the middle class, thus elevating the wealthy strata of society in to one social and political unit that acted in unison. While there were class distinctions between the landed gentry and the factory owners, the sharing of political power had the practical effect of severing all ties with the lower classes. These ties, for the nobility, had been ties of responsibility or of patronage, a sense that the tiled masters of the realm had a moral and ethical responsibility toward their laborers. The connection, for the middle class, was one of origins and proximity, as the working class or the lower class, found economic success. But by the mid nineteenth century the working classes and their less successful corollary “the poor” were left behind and a huge gulf opened between people who actually lived very closely together. One can only speculate that it was this very closeness in which the working classes worked to benefit the upper (aristocracy and “middling ranks”) classes that made it necessary for those of the lower orders to become invisible to those who actually depended upon them. It was the work of John Thomson that rendered the trades of the streets of London visible.

John Thomson. “London Cabmen,” from Street Life in London (1877)

In the second part of this topic, the mode of representation, documenting the poor or London, will be discussed.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.