Eadweard Muybridge: Photographing Colonialism

Part Three

Although the relationship between Eadweard Muybridge and Leland Stanford would send the photographer down a path that led to one of the main art forms of the twentieth century, the photographer, the cool killer of his wife’s lover, undertook two smaller and lesser known commissions, one before and one after the celebrated murder. Professional photographers out in the field in the West often found themselves witnesses to historical changes due to the workings of imperialism and colonialism where were powerful forces during the nineteenth century. One might note that, once a military machine been set in motion, America found it hard to simply stop and the militaristic energy turned west and was turned on indigenous peoples. “Winning the West” would consist of a series of small and nasty wars that were clashes between cultures and technologies in which the so-called more “civilized” Americans who displayed a savage ruthlessness is wiping out any opposition to their “manifest” destiny. In subduing the Modoc nation and removing the tribe from their lands at the California and Oregon border, the United States herded the Modocs, forcing them to live with their ancient enemies, the Klamath peoples on the Klamath Reservation. The Modocs refused to live on the reservation and the result was another nasty and expensive war in which the outnumbered and outgunned Native Americans found the army of the United States government to a standstill for almost a year. Led by “Captain Jack,” the Modocs were finally run to ground and the leaders of the defeated band were captured, tried, and executed by the government. According to Peter Palmquist, in “Imagemakers of the Modoc War: Louis Heller and Eadweard Muybridge,” in an act of final grotesquery, the army beheaded (postmortem) four of the most prominent members of the uprising and sent the heads to the Army Medical Museum.

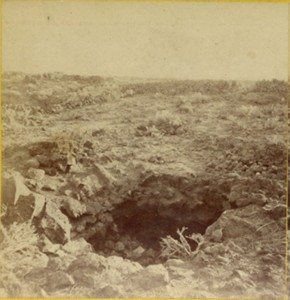

Eadweard Muybridge. Captain Jack’s Cave in the Lava Beds (1873)

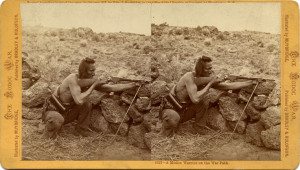

A few months after ending the question of the position of the feet of horses when they ran, Muybridge was summoned to the battlefields of northern California, far beyond San Francisco. When Muybridge, who had been hired by the government to record the battle grounds, which were the lava beds of Tule Lake, arrived, there were still renegade Modoc warriors on the loose. In contrast to the private and commercial ventures of Matthew Brady during the American Civil War, what was unusual about the Modoc War is that the government itself and asked Muybridge to photograph the sites of conflict. The other photographer present, Louis Heller, was a freelancer who was working in his own “territory,” while Muybridge was an “official” photographer providing a documentation of the war for the government. In the Spring of 1873, Muybridge acted in the same manner as Brady’s operatives and Roger Fenton in the Crimea and photographed the aftermath of conflict. The famous image of a Modoc warrior by Muybridge is a reenactment, posed after the defeat by a scout for the United States Army.

Eadweard Muybridge. The Modoc War (1873)

While Muybridge was far away from his wife photographing the evidence of an insurrection, his wife Flora found herself some amusement, the result of which was the murder, the surrender, the trial and the acquittal for the ‘crime of passion.” For the next year Muybridge, now sporting a totally white mane of hair and a long Santa beard, removed himself from his adopted country so that the scandal that swirled around him could diminish. He took a commission from the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, a firm that was attempting to lure tourists to Guatemala. By the end of the nineteenth century, there was little left of historic Mayan culture, much of which had been wiped out by the invading Spanish who had helped themselves to the averrable land. In the beginning of the century, the nation supported itself, expanding upon its traditional way of life, by exporting Indigo, or “xiquilite,” the native Nahuatl word, and cochineal, another dye, this one red and made from crushed bugs. Although by mid century, “Guatemala indigo,” or aniline dye, was driven out of the dye business, it is worth nothing that the great contemporary purveyor of coffee, Starbucks, decided in 2012 to stop using red (dye) number 4 (cochineal). After a blight ruined the indigo plantations, new crops, including coffee was introduced and it was coffee that came to dominate the entire nation, which continued its existence as a vast plantation. Guatemalan dictator Justo Rufino Barrios passed out any remaining Mayan lands to speculators and investors and created a network of large coffee plantations, or fincas, that covered the sloping mountain sides. Under what was called the “the Liberal Reform,” Barrios sold public land to private interests and part of these “reforms” was using the military to quell the protests of the indigenous peoples over the seizure of their lands.

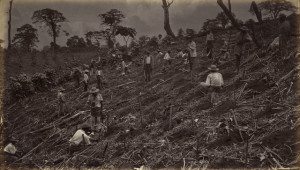

Eadweard Muybridge. Setting out a Coffee Plantation at Antigua de Guatemala (1875)

Presumably under the assumption that future tourists would find the art and science of coffee production on vast plantations fascinating, Eadweard Muybridge, present at the creation of a new monoculture, carefully and systematically recorded all stages of the growing of coffee. What can be seen nearly 300 photographs is that during the 1870s, Guatemala was in the midst of a great colonial transformation in the name of industrialization and development. Guatemala was Mayan territory and there was a Mayan population that had claims to the land, but ancient rights were no match for the growing market for coffee, a staple in most households in Europe and America. Muybridge caught the contrast between ancient scenic highlands of Guatemala and the primitive but burgeoning industrial production of coffee.

Eadweard Muybridge. Ruins of a Church, Antigua, Guatemala (1875)

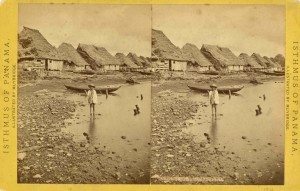

The trip to Guatemala was but part of an extended nine month excursion into Central America. Muybridge went to Panama stopped off at towns along the coast, photographing the lands and peoples of a world entirely new and novel for North Americans. Panama during the 1870s was still virgin land and the Canal was ten years away from being built. The French would show up in the late 1880s in what would be a failed attempt to cut across the isthmus.

Eadweard Muybridge. The Isthmus of Panama (1875)

In contrast to his work at the coffee plantations, his images of San Isidro show an untouched world, still, for the moment shelter from incursions by Western powers. Like his images of Guatemala, Muybridge’s records of Panama show a land at a moment of transformation. In Guatemala, change has already come, in Panama, time is running out. Already, thanks to the Gold Rush, America was building railroads to connect Panama to California. For centuries, under the Spanish, Panama had been the nexus point for the “Columbian Exchange,” or the trade between Europe and Latin America. By the seventeenth century Spanish occupation had resulted in the death and demise of the native population and Panama became the focal point for trade in slaves from Africa. Panama was able to disentangle itself from Spain when Napoléon conquered the Iberian Peninsula, but its strategic location was so important to trade and commerce, the nation would not become fully independent until the 1970s.

Eadweard Muybridge. San Isidore (1875)

Muybridge was part of an American influx into Panama, a peaceful business invasion perpetrated solely on behalf of American investors. Fifty years earlier President James Monroe had issued the aspirational Monroe Doctrine, declaring Central and South America to be within in America’s “sphere of influence.” The original idea was to warn off the French and the British but, by mid-century, the “influence” was economic and frankly exploitative. As Robert Harding explained in his 2006 book, The History of Panama,

Thousands of local workers were left unemployed, disgruntled, an angry both at the American company and at the American company and at the growing American control of the entire zone surrounding the railroad. The American community had grown quickly and became a contending economic and cultural fore. Panamanians were beginning to feel like foreigners in their own land. Americans also brought with them virulent racism common at the time in the United States, insensitivity toward Panamanian culture, and a sense of superiority that bordered megalomania.

Muybridge, like his counterparts who acted as photo-documentarians, was a reporter who was expected to explore with his camera, but he was also working on company time, so to speak. We cannot expect from professional photographers of the late nineteenth century a critical mindset or a contemporary social awareness. Certainly he was complicit with the forces of imperialism and colonialism, but what makes these two bodies of work in northern California and in Central America interesting is the book end effect of these images. In recording the last of the Modocs and the vanishing world of the ancestors of the Mayans, Muybridge unwittingly recorded the end of cultures and civilizations that would become only distant memories as they were destined to be swamped by that tide called “progress.” And then, there was the technological challenge of photographing a fast moving object quickly, a problem that would open the door to a new century. After a year of travel, Eadweard Muybridge was ready to return home to San Francisco.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.