Eadward Muybridge in Yosemite

Eadweard Muybridge lived many lives under many names, rose and fell, appeared and disappeared, invented and re-invented himself. In the nineteenth century, you could do that sort of thing. This was a century of non-identity, meaning that, lacking the technology we have today that fixes you in time and place, sets your name in stone, and forces you to move through life, dragging your past behind like flotsam and jetsam. The Victorian era allowed you to arrive at a new station, check your luggage in the left luggage compartment, walk out, recreate your new self and never return retrieve your old self, leaving your life luggage to languish, forgotten. While industrial enthusiasts spoke of “shrinking time and space” with locomotives and telegraphs, a poor woman from a European city could slip seamlessly into a new occupation in the vast American wilderness with a new future before her. The son of a corn merchant, a corn handler, named Edward James Muggeridge could christen himself “Eadward,” after two English kings, Eadward the Elder, Eadweard the Martyr, and “Muybridge,” acknowledging the fact that “muy,” as Hollis Frampton reminds us, was a measure of dry grain. But this charming an homage to one’s English town of origins, Kingston (king’s town), site of the Coronation Stone for Saxon kings, the elaborate name change was a mere prelude for a photographer, who got away with murder, because one could do that sort of thing then.

It is very rare for art history to spend much time writing about an artist who is also a murderer, but the career of Eadweard Muybridge is a exception to expectations. Like many European men stranded in small towns without much future, Muybridge sought his fortune in America and reinvented himself in San Francisco where he entered the quiet trade of selling books, a trade that was an indication that a town made famous and rowdy by the Gold Rush was becoming civilized. But this relatively quiet new beginning was interrupted when the young business man was involved in a stagecoach accident in Texas, when the coach in which he was a passenger plunged down a mountainside. According to Arthur P. Shimamura in “Muybridge in Motion:Travels in Art, Psychology and Neurology,” this 1860 incident was a severe one:

Prior to his accident Muybridge was a good businessman, genial and pleasant in nature; but after the accident he was irritable, eccentric, a risk-taker and subject to emotional outbursts. The emotional changes that followed Muybridge’s head injury are familiar to neurologists. Damage to the anterior part of the frontal lobe, known as the orbitofrontal cortex, disrupts the control and regulation of emotions. In modern times, damage to this region is a common consequence of severe automobile accidents.

After recuperating in Arkansas and consulting doctors in New York, Muybridge concluded that the accident that he could not remember was bad enough that he had to return to England where he spend the next five years in convalescence. It is assumed that the bookseller studied photography, because, when he returned to the West, Muybridge became a professional photographer. It is also quite possible that while in San Francisco for the first few years of his immigration, he had noticed the growing population of the sophisticated new city and the national appetite for photographs of the fabled frontier where “wild Indians” “savagely” attacked the well-meaning settlers and fought against the encroaching railroads. This West of the dime novels and the source of the fertile imagination of the authors of pulp fictions absorbed a slightly psychotic English photographer who set out to Yosemite to follow in the footsteps of Carleton Watkins and Charles Weed, adding a third voice to the trio of pioneer image makers who lugged the heavy tools of their trade into the wilderness.

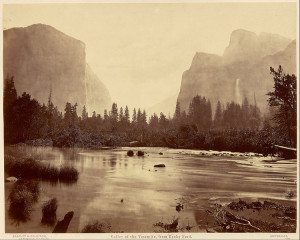

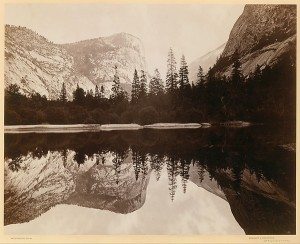

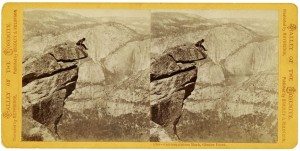

It is at this point in time when the final reincarnation of the photographer took place: Muggeridge became Muggridge, which became Muygridge, finally wrestled itself into its final spelling “Muybtidge.” But the name change did not end there, for “Edward Muybridge,” after painstakings tryouts, also had an alter ego, because as a professional photographer, he practiced under the name, “Helios.” By 1867, he was in Yosemite, conscious of his precursors, and photographing some of the same sites. What is not known is how he developed him unique style, for the vantage point favored by Muybridge often allowed the composition to be divided horizontally in the middle. At first glance, it seems that the photographs were simple Claudian structures, adapting the classical paintings of Claude Lorraine, a sliver of a foreground, a generous middle ground and an open Baroque expanse into the open background which melted into the sky. But Muybridge had a penchant for reflections and turned Claude’s seascapes into mirrored landscapes that bifolded themselves and then reflected themselves and then doubled themselves, as if for emphasis.

Eadweard Muybridge. Valley of the Yosemite, from Rocky Ford (1872)

Although Muybridge invented a sun shade to help reflect the glare on the camera, the skies are, at this stage of photographic invention, blank and act as a visual relief to the complex detail of the site itself. Twenty of these original photographs appeared in 1868 in Yosemite: Its Wonders and Its Beauties, perhaps the first guide book to the national park, written by John Hittell. The title page proclaimed in great detail on the title page: “With Information Adapted to the Wants of Tourists About to Visit the Valley…Illustrated with Twenty Photographic Views Taken by “Helios,” [Edweard J. Muybridge] and a Map of the Valley.” Hittell commissioned Muybridge to photograph the views, because, as he explained,

“The sublimity, the variety, and the unparalleled greatness of the scenery of Yosemite, render it worthy of illustration by pen and picture. The people of California feel a general interest in the valley, which is one of the most remarkable natural features of their wonderful State. Many have visited the grand chasm, and want something to recall by association the adventures of their trip and the pleasures of their stay. Others intend going, and wish advise in regard to the most impressive views and the best method of traveling. And all desire to be familiar with the general appearance of that world-famous collection of cliffs, cataracts, domes and dells. This book is published to supply the want. It is small so that it can be used as a guidebook; it is cheap so as to be within the reach of all; it is illustrated so that the reader can see the mirror held up to nature; and the illustrations are photographs, because no engravings could do justice to the scenes, or convey perfect confidence in the accuracy of the drawings of such immense elevations as those of Tutucanala and Tissayac.”

The twenty photographs were originals, mounted onto the pages. Over time, they would buckle somewhat, which was to be expected. But the guidebook laconically elides an ugly history which is the seizure of this beautiful land from the inhabitants who had lived in the Valley for thousands of years, first in 1851 by the state of California and then in 1864 by the federal government. The photographs of Muybridge are frozen and still, as though time does not exist and fleeting moments simply stand still and gaze in awe at the soaring peaks of steep mountains. No humans penetrate this Edenic beauty, apparently known only to God and the intrepid photographer. Each perfect image gives the viewer the impression that these sites were untouched and that perhaps Muybridge himself was discovering these dramatic landscapes. And yet the guide book invited tourists, both armchair and actual travelers to visit and experience the awe for themselves. Of course, Yosemite was already a tourist site, with its own hotel, a decade before Muybridge arrived, the the Hutchings House, operated by James and Elvira Hutchings from 1864.

Image by Muybridge in Guide Book

Muybridge stayed at the Hutchings Hotel and made it his headquarters for this season of photography and, going beyond the vistas established by Watkins and Weed, he returned with some seventy-two mammoth plates and one hundred The pristine state of a national park owes its protected state to the discovery of gold in California in the late 1840s. By 1848, the discovery of gold started the internationally famous Gold Rush, which lured even Chinese adventurers to the “gold mountain.” Although the Native Americans naturally joined in the hunt for gold on what was, after all, their land, even inventing the sluice box for panning, they were soon driven off by white authorities. Stories of Stanislaus by Sol P. Eilas provides a sympathetic portrayal of the fate of the Native Americans, as the author stated bluntly, “After the discovery of gold, the Indian was treated as an intruder in his own ancient habitat and as a common enemy by the whites. In many instances he was shot down with as little compunction as was a deer or the antelope..” The native women were seized by male settlers and miners for sexual slavery, the native children were sold into slavery as workers, and in an attempt to restore order, the Congress ordered federal agents to negotiate some eighteen “peace and freedom” treaties that gave the tribes of California ten reservations on some eight and a half million acres. The white settlers received the state of California in return. In such a huge state even millions of acres is a pittance but the Native Americans did not receive even this paltry bit of territory–after all, this land held gold, none of which, not one nugget, should fall into the hands of its original owners. The eighteen treaties were mysteriously “lost,” perhaps at the behest of someone in a Congress, nervous that the natives might enrich themselves.

The typical attitudes of the day towards Native Americans echoed the attitudes towards African Americans and other peoples of color in white America. Elisa quoted F. W. Rice, junior editor of the Courier, as saying,

“Previous to the gold discovery these Indians lived on acorns and clover, occasionally catching a few fish. Now they get a little meat and occasionally bread with the money they gather by rocking the cradle for the miners, or for the small amount of gold dust which they muster industry enough once in a while to dig themselves. The gold diggings are right in front of the encampment and the few Americans who are working them, get them five to eight dollars per day, now that the river is low. There are few of these Indians who wear clothing, after the fashion of the miners, and who seem to have a little pride in red shirts and gaudy cotton handkerchiefs; but the mass of them have no such ambition.”

The displaced population was ordered out of California by the Assembly of that state and told to go “beyond the limits of the state in which they are found with all practicable dispatch.” Some were shipped to Alcatraz, some were simply dumped into the Pacific Ocean, and, by 1900, when Yosemite became a national park, only 16,000 of indigenous Californians had survived the attempted exterminations. Following the march of the Mariposa Battalion into Yosemite Valley in 1851 under orders to remove the Ahwahneechee and the Yosemetes, the territory, now free of entanglements with strangely “lost” treaties, was granted by President Lincoln to the State of California in 1864. Indeed, the fate of California’s Native Americans, as Stephen Powers noted in in his 1877 book Tribes of California, was a tragic one:

They were once probably the most contented and happy race on the continent … and they have been more miserably corrupted and destroyed than any other tribes within the Union. They were certainly the most populous, and dwelt beneath the most genial heavens, amidst the most abundant natural productions, and they were swept away with the most swift and cruel extermination.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.