Edward Alexander Wadsworth (1889-1949)

In 1914, Wyndham Lewis (1882-1957) writer, pointer and leader of a band of English radical artists issued the Manifesto for a new avant-garde movement, Vorticism, designed to counter the exhortations of Futurism. In “Long Live the Vortex” he declared:

Our vortex is not afraid of the Past: it has forgotten it’s existence.

Our vortex regards the Future as as sentimental as the Past.

The Future is distant, like the Past, and therefore sentimental.

The mere element “Past” must be retained to sponge up and absorb our melancholy.

Everything absent, remote, requiring projection in the veiled weakness of the mind, is sentimental.

The Present can be intensely sentimental—especially if you exclude the mere element “Past.”

Our vortex does not deal in reactive Action only, nor identify the Present with numbing displays of vitality.

The new vortex plunges to the heart of the Present.

The chemistry of the Present is different to that of the Past. With this different chemistry we produce a New Living Abstraction.

The Rembrandt Vortex swamped the Netherlands with a flood of dreaming.

The Turner Vortex rushed at Europe with a wave of light.

We wish the Past and Future with us, the Past to mop up our melancholy, the Future to absorb our troublesome optimism.

With our Vortex the Present is the only active thing.

Life is the Past and the Future.

The Present is Art.

There is a great deal more where that came from, but Lewis, writing in the first (and second last) issue of BLAST, demanded that the artist live in the present. The Cubists lived in the past, honoring French traditions; the Futurists yearned for the future; only the Vorticist artists lived fully in the present, the now. In retrospect, this stance, emphasizing acting and being in the moment, gained a certain poignancy, with the Great War just weeks away, the now was all that many young men would have. In the very brief time, the few months before the Great War began, when a few rebellious English artists in London came together under the banner of Vorticism, Lewis was mainly concerned in making sure that the public understood what Vorticism was not. As his advertisement in The Spectator announced,

The Manifesto of the Vorticists. The English Parallel Movement to Cubism and Expressionism. Imagism in poetry. Death blow to Impressionism and Futurism, and all the refuse of naïf science.

The fact that mere months earlier the Vorticist artists had appeared in an exhibition combining Post-Impressionism with Futurism in the Doré Gallery made the explanation of the goals of Vorticism imperative. But the now-strange juxtaposition of the two movements, one of the nineteenth century and one of the twentieth century, colliding in an art exhibition, was a portrait of the English art scene.This was an art scene that, so far, had fail to spawn an English avant-garde movement, an art scene still in the grips of the previous century, and, when confronted with European art, one that was not particularly interested in Cubism. As the name indicates, the Doré Gallery had been established for the purpose of exhibiting and supporting the art of Gustave Doré, but its space was also available for other exhibitions. In 1913 the last year of its operation, the Gallery, commissioned Frank Rutter (1876-1937), an art writer to curate an exhibition, Post-Impressionist and Futurist Exhibition. Perhaps because Lucien Pissarro (1863-1944) had close connections to the London art world, Rutter began his version of avant-garde progression with Camille Pissarro, to counter the selection of Édouard Manet and Paul Cézanne provided by Roger Fry (1866-1934) in 1910. Rutter, who, in his spare time, was a leading voice in the Men’s Political Union, which supported women’s suffrage, had helped to publicize the term “post-impressionism” and sought to drag British art into the twentieth century. The Post-Impressionist and Futurist Exhibition exhibition was significant because it followed Fry’s attempts to construct a chronology of modern art, and Rutter included English artists in his time line. The catalogue for the show stated that

..this exhibitions an attempt to set forth in a coherent and so far as possible in a chronological order examples of various schools of painting which have made some noisier the world during the last quarter of a center.” He continued, “That ‘cubism’ and ‘futurism’ have already stirred English artists is shown by the contributions of Mr. Wyndham Lewis, Mr. Wadsworth, Mr. Nevinson and others.

The leader of what was the first and only English avant-garde movement, Vorticism, Wyndham Lewis, insisted that only the British artists could fully understand modern art and modern life, because it was in England that the Industrial Revolution began, stating, “The Modern World is due almost entirely to Anglo-Saxon genius.” In fact, being from the upper classes, most of the Vorticist artists had little experience with machines and industry. All except one artist. Hailing from the Industrial heartland of the British Isles, Edward Wadsworth was the best-educated and best-prepared to celebrate the industrial revolution and all that that social and political “event” had wrought. Like Wyndham Lewis, Wadsworth came from a wealthy family in Yorkshire, but he was educated in Munich to be an engineer. His father expected him to follow in the family business, E. Wadsworth & Sons, a worsted-spinning enterprise in Cleckheaton. The well-laid plans went awry and the decision to polish the son and heir in Munich proved to be a mistake. While improving his German, Wadsworth translated a small book by a Russian avant-garde artist, Vassily Kandinsky, currently working in the area. Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1912) inspired Wadsworth to become, not an industrialist, but an artist of industry.

John S. Currie, Some Later Primitives and Madame Discern (1910)

Left to right: Currie, Mark Gertler, C.R.W. Nevinson, Edward Wadsworth, Adrian Allinson and Madame Tisceron

With the intention being an artist, Wadsworth returned to England to attend the Bradford School of Art and the famous Slade School, from 1909 to 1912, where he met the future Vorticists. Perhaps the training that marked him most profoundly was that of restoring paintings by sixteenth century artist, Andrea Mantegna, under the tutelage of Roger Fry. Because the Renaissance artist had used egg tempera, Wadsworth had to learn how to master the laborious process, which, unlike oil was unforgiving. Wadsworth was trained to have a sure hand, one well suited to producing works of art dedicated to industry. Unlike the personalized painting styles of the Impressionists and post-Impressionists, Wadsworth pioneered in a neutral mechanistic style of drawing in flawless outlines and filling in shapes and designs with flat uninflected paint. The result was the abolition of the “hand” or the unique touch of the artist himself in favor of depersonalized application of materials within a design that was inspired by the Vorticist mash-up of Cubism and Futurism.

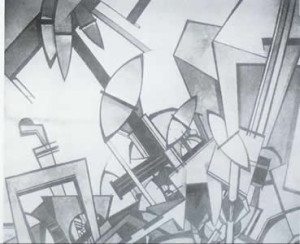

Edward Wadsworth. Cape of Good Hope (1914) (lost)

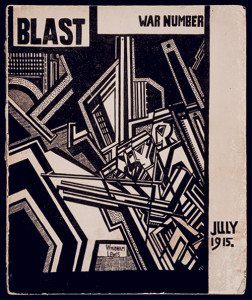

Along with the other London artists, such as Jacob Epstein and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Wadsworth became involved with the Vorticists, an association which meant pulling away from his mentor Roger Fry and siding, as it were, with ringleader Wyndham Lewis, a Canadian, and his associate Ezra Pound (1885-1972), an American, who suggested the name “Vorticism.” Lewis and Pound promoted Vorticism and the artists of the movement through BLAST, and the work of Wadsworth appeared on the cover of the second and last issue.

The breakaway artists formed another group, the Rebel Art Centre in order “to familiarize those, who are interested, with the ideas of the great modern revolution.” According to art historian Timothy Materer, the Vorticists looked to the machine and the city, artificial creations of the Industrial Revolution, as their source of inspiration. Eschewing the natural, Vorticist art was composed of “the forms of machinery, factories, new and vaster buildings, bridges and works” of the dehumanized “iron jungle.” A year after the establishment of the Centre, the first Vorticist exhibition was held in June 1915 at the hospitable Doré Gallery, included the official “Vorticist artists,” Jessica Dismorr, Frederick Etchells, Helen Saunders, William Roberts, and Edward Wadsworth, and sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzesk, and some related artist, such as Canadian artist, David Bomberg, British artist Duncan Grant and the English Futurist, Christopher Nevinson. The news of the death of Gaudier-Brzesk on the battlefield overlaid the exhibition, the first and last in which the Vorticist artists were together. Sadly, for our understanding of many of these artists, these early but seminal works have been lost.

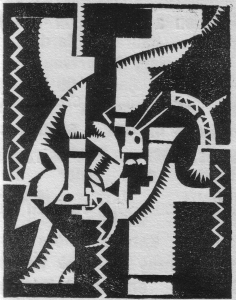

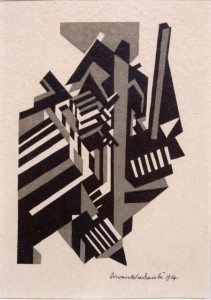

Edward Wadsworth. Newcastle (1914)

Although Wadsworth did some paintings (mostly missing), by 1914, he was already making woodcuts, the medium of choice for the next decade. There is letter that Gaudier-Brzesk wrote to Wadsworth on November 18th in 1914, very early in the War, thanking him for the woodcuts. “I have your letter with the woodcuts; it’s a relief to touch civilization in its tender moods now and then.” The sculptor mentions Flushing and preferred the print, Rotterdam, which along with the other works he had received were “quite new to me.”

Edward Wadsworth. Rotterdam (1914)

In the following year, the Vorticist artists were discussed by Lewis in BLAST in March 1915, a write up that included Wadsworth.

Mr. Edward Wadsworth’s Blackpool appears to me as one of the finest paintings he has done. It’s striped ascending blocks are the elements of a seaside scene, condensed into the simplest form possible for the retaining to its vitality. It’s theme is that of five variegated cliffs. The striped swings of Cafés and shapes the stripes of bathing tents, the stripes of bathing machines, of toy trumpets, of dresses, are marshaled into a dense essence of the scene.The harsh jarring and sunny yellows, yellow-greens are especially well used, with the series of commercial blues. One quality this painting as which I will draw special attention to. Much more than any work exhibited in the last year or so by any English painter of Cubist or Futurist tendencies it has a quality of life..To synthesize this quality of life with the significance or spiritual weight that is the ark of all the greatest art, should be, from one angle, the work of the Vorticists. (Note that Lewis did not know how to use “its”or “it’s,” which he used incorrectly on both occasions.)

What makes the inclusion of Wadsworth interesting is that he used his unimpeachable credentials as the heir to a huge industrial production in Yorkshire to produce images of twentieth century industrialization in the ancient modes of tempera and woodcut, media worth of a Renaissance artist. What we know of his lost paintings can be found through the extant woodcuts based on the paintings.

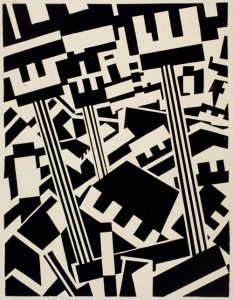

Edward Wadsworth. View of a Town (1914)

The avant-garde tradition in all Western nations would be marred by great losses, particularly after 1930, when much of the art fell under the power of hostile totalitarian regimes, but the missing work of the English Vorticist artists were the first to disappear, usually by the hands of the artists themselves.

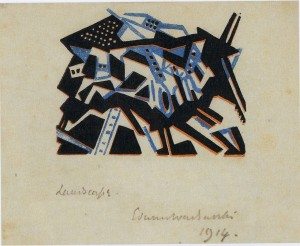

Edward Wadsworth. Landscape (1914)

Wadsworth was separated from his colleagues by the War. As shall be seen in the next post, he joined the Navy where he produced his most famous and characteristic works. The last great avant-garde body of work produced by Wadsworth was a series of woodcuts on the Black Country, the dark heart of the industrial heartland of Great Britain. The rest of the work of Wadsworth, the bulk of his production, was a renunciation of Vorticism and all that it stood for. In his sudden conversion to conservatism in art, Wadsworth was typical of the post-war generation, heeding the call to “return to order.” But there was one last and extraordinary body of work to come from Wadsworth that epitomized modernity, his War work, discussed in the next post.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.