Edward Wadsworth (1889-1949)

The Artist at War: The Dazzle Ships

If the Great War can be characterized by any one metaphor it would be that of the Closed Mind and a Determined Refusal to accept the mechanization of war. On land, strategy and tactics remained fixated on the Napoleonic tradition, and at sea, the approach to naval warfare was based upon steam power. In the nineteenth century, slow moving sailing ships would customarily cluster together, both for mutual support and protection and as an all-important part of battle tactics. The most famous example of warfare by convoy was the Spanish Armada. Therefore, in the time of sail, naval convoys were commonplace, but conventional wisdom decreed that the speed of steam made such protection obsolete..or so it was thought until the Germans redefined war at sea. Once a rarity or a novelty, submarines, especially those under German command, began to develop their own rules–“unrestricted” attacks on any and all vessels, even neutral nations, which attempted to supply the nations of the Entente Cordiale. But the idea of “unrestricted” can be expanded to an abandonment of the rules of wartime gallantry or courtesy to the foe. An enclosed tube with a small crew and even less interior space, a submarine could neither retrieve the surviving sailors of the ships it sunk, nor could it spare a submariner to pilot a captured ship. As as a result of practical necessity, the German submarines simply sank Allied boats and sailed away, allowing the crews to drown. As an early German account of a 1914 sinking stated, “In the periscope, a horrifying scene unfolded… We present in the conning tower, tried to suppress the terrible impression of drowning men, fighting for their lives in the wreckage, clinging on to capsized lifeboats…”

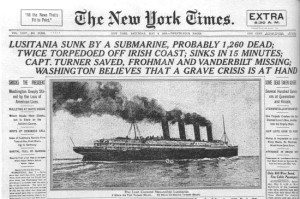

“Unrestricted” had yet another ramification–attacks on merchant ships, non-military vessels. Germany understood clearly that England was an island and that it depended upon its navy to protect its interests. To engage the Royal Navy on two fronts, fighting it at sea, ship to ship, and splitting its attention by sinking its life lines, merchant ships, with submarine warfare would be to divide and conquer. Unrestricted submarine warfare began in February of 1915, and, although the supposedly neutral vessels were, for the time being, afforded safe passage, in May of that year, the American ship, the Lusitania was sunk by U-20 under the command of Walther Schwinger. It would take nearly one hundred years for it to be confirmed that the Lusitania did indeed carry munitions, but at the time, the torpedoing of an American ship off the coast of Ireland was nothing short of a war crime against defenseless civilians. Schwinger wrote in his log, “It looks as if the ship will stay afloat only for a very short time. [I gave order to] dive to 25 metres and leave the area seawards. I couldn’t have fired another torpedo into this mass of humans desperately trying to save themselves.”

The use of submarines tipped the balance of power between the German and British navies. No one was prepared for the introduction of large numbers of submarines into naval warfare. Due to its superior size, the British Navy may have been slow to awaken to the dangers of the submarine and clung to their old habits of traditional warfare at sea. Meanwhile Germany took the unprecedented step of sinking civilian ships with no warning and no quarter. The submarine would stalk a targeted ship, and, when it was within range, the submerged vessel would surface and attack. For reasons that seem unclear today, during the Great War, the British government, its military branch, was loath to commit a sizable number of ships to a convoy system, which would convey a herd of ships safely to ports. Having been pulverized for three years by lethal attacks from German U-boats, the Royal Navy began to realize that “war at sea” in modern times meant dueling with submarines. By 1917, after huge losses to Allied shipping, especially the trans-Atlantic route, the British finally announced in May a revival of the convoy system. Only by going back in time, did the Royal Navy finally starch its bleeding and regain its dominance of the waves.

But the tale of the convoy was but part of the story. A new camouflage for ships was invented. As pointed out in a previous post, compared to a stationary site, a moving target is very hard to conceal, especially under the changeable circumstances at sea. However, early in the war, a British embryologist, Sir John Graham Kerr (1869-1957), who recognized that certain large animals, such as zebras, were both mobile and concealed (in herds or convoys). Kerr wrote to the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, making the case of confusion over concealment. He stated, “It is essential to break up the regularity of outline and this can be easily effected by strongly contrasting shades … a giraffe or zebra or jaguar looks extraordinarily conspicuous in a museum but in nature, especially when moving, is wonderfully difficult to pick up.” Churchill quickly ordered the adoption of “parti-coloring” and initially it was noted that such disruptive coloring made it difficult for enemy ships and submarines to find an accurate range. However, after the disastrous campaign in the Dardanelles, Churchill resigned and the Navy reverted back to the customary gray color.

The same year that the British, in desperation, reverted to the convoy system to protect its fleets, a marine artist, known for his picturesque seascapes, Norman Wilkinson (1878-1971) presented the Admiralty with a way, not just to protect ships but to also confuse the enemy that hunted them. “Dazzle camouflage” was a variation on “parti-coloring” but had the same intent. As Wilkinson explained in 1919:

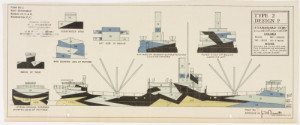

The primary object of this scheme was not so much to cause the enemy to miss his shot when actually in firing position, but to mislead him, when the ship was first sighted, as to the correct position to take up. Dazzle was a method to produce an effect by paint in such a way that all accepted forms of a ship are broken up by masses of strongly contrasted colour, consequently making it a matter of difficulty for a submarine to decide on the exact course of the vessel to be attacked..

The weak point of warfare at sea, particularly for submarines, was finding the “range.” Dazzle camouflage, as imagined by Wilkinson was geometric, not organic, a graphic design, rather than an imitation of nature itself. The extent to which the operator of the range finder could be confused depended upon the efficacy of the design that would be painted on the surface of all Allied ships. The Dazzle or Razzle Dazzle graphics made it quite difficult to determine whether the ship was heading east of west, moving fast or slow, riding high or low in the water. The zigs and zags made it a challenge to know where the center of the ship was. Dazzle camouflage was based upon the type of rangefinder used by the Royal Navy. This rangefinder was “co-incident,” meaning that two images had to be merged into one uniform image. This mode of finding the range–place and distance–was very accurate. Dazzle camouflage, as seen through the British rangefinder, was very effective. But apparently unknown to the British Navy, the German fleet used another kind of rangefinder, a stereoscopic system. Designed by the Zeiss Optical Company, the stereoscopic system has a double image but, unlike the British images, the German device, according to Peter Lienau, could not be fooled by the camouflage.

Nevertheless, Norman Wilkinson was put in charge of a Dazzle camouflage unit, which, for the last year of the War, painted four thousand merchant ships in various patterns of strips, designed by a corps of artists.

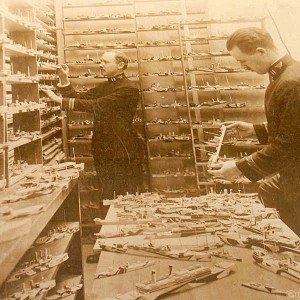

The secret naval unit was a seventeen member team, comprised of five male artists and eleven female art students and three model makers.

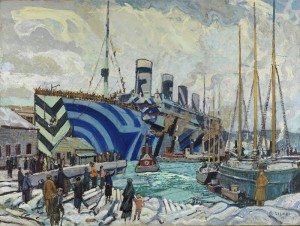

Eventually over four hundred British war ships were “dazzled,” starting with the HMS Alsatian in late summer of 1917, by a team of ten supervisors in the field. Former passenger lines, used as troops ships, were also disguised by graphics and one can only imagine the array of colors and patterns floating on the Atlantic Ocean, across the English Channel and over the Mediterranean, disembodied in the sifting lights and shadows.

Although dazzle camouflage was used through the Second World War, it seems to have been rejected by Hollywood historians and the idea that the navies of the Allies were camouflaged often comes as a surprise to those who learn history in movie theaters. But by the time the war ended over two thousand ships of the Great War had been painted and patterned in vivid colors that are blunted by old black and white photographs. The Dazzle designs were tested at the Dazzle Section at the Royal Academy of Arts in Burlington House in London on scale model ships. These painted models were then viewed through periscopes to determine the effectiveness of the proposed design. Once approved, the design would be applied to designated ships at their home docks. But there is something odd here that needs to be noted: for some reason, the information on Dazzle ships is riddled with a surprising number of errors from sources that appear to be reliable. Although there is no particular reason to think that the artists did not look at the models through a periscope, the question is why? The pertinent instrument that needed to be tested with the Dazzle design was the rangefinder itself, which was used to target the ship.

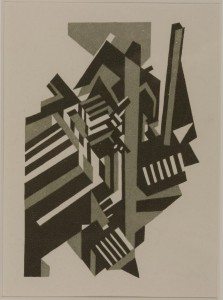

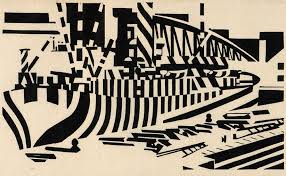

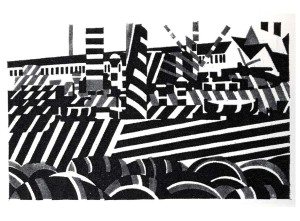

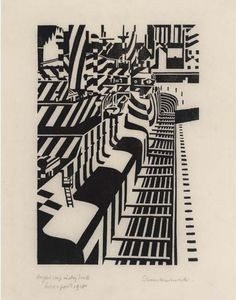

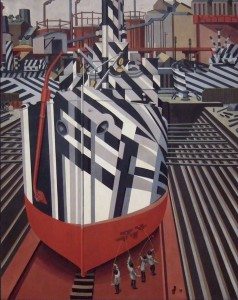

To expedite the painting, Wilkinson appointed dock officers, to oversee the jobs. One of his appointments was the Voricist artists, Edward Wadsworth, now a camoufleur. However, the relationship between Vorticism and Dazzle camouflage is unclear. Wilkinson was anything but avant-garde and the extent to which he might have learned anything from Vorticism is unclear. In addition, Wadsworth, Vorticist artist or not, was in the Navy and had to follow orders: he painted what he was told. However, one of the characteristics of Wadsworth’s Vorticist prints was mis-direction: one had to look carefully in order to determine the content or subject, much less the direction of his content. The woodcuts produced by the artist had, like his paintings, the look of an object crushed and turned in upon itself, twisting and convulsed.

Like Wilkinson, Wadsworth was a member of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, actively engaged in the War itself. Ironically, the artist is best known for his prints of the Dazzle ships he so carefully supervised and it is clear from this large body of work, Wadsworth was fascinated by the visual effects of these ships. The artist responded to the ships and their geometric designs with a series of woodcuts, limited to black and white. As with his prints from the Black Country, the viewer is challenged by Wadsworth’s novel perspectives. Although on one hand, his vantage points seem relatively straightforward, on the other hand, the views of the ships are totally imaginary. Moored to the docks, standing docilely while receiving the painted lines, the vessels were actually quite large, and the artist would have seen only a part of the hull at a time. Once he had completed the task, Wadsworth would have had to pull back a great distance to view the entire design. Notice that most of the images of Dazzle ships are photographs taken from some distance.

Wadsworth does not seem to have sought a dramatic perspective as much as he was interested in doing in his prints what the ships were supposed to do at sea: disappear. Compared to the intricate pre-War designs of Wadworth, the dazzle ships, in real life, are cleanly stripped and apparently legible. And yet, when Wadsworth places them into a graphic format, the ships vanish into a maze of lines and are absorbed into the vortex of modern war. The artist understood the designs, perhaps from the perspective of a Vorticist artist who reimagined the Machine as being intertwined with life and death itself. Wadsworth combined the role of graphic designer and fine artist in the post-Vorticist prints.

The flatness of the prints seemed to appeal to the artist who, by 1922, switched from oil to goache for a matte finish. Although Wadsworth became a Surrealist and a representational artist in the 1930s, he is best remembered for his visual graphics which echoed the very designs he painted on the Dazzle ships.

The ships themselves were considered by some to be avant-garde, so clear were their modern art affinities. Described as “floating Cubist paintings” and a “Futurist bad dream,” mostly by those who had only passing familiarity with either style, the array of ships in port resembled an art exhibition in a gallery. So famous and so effective an advertisement for “modern art,” the art of camouflage was celebrated at the 1919 Chelsea Arts Ball. According to James Fox in his 2015 book, British Art and the First World War, 1914–1924, the Ball “featured a vast dazzled ship painted by Norman Wilkinson himself..” Fox described the event as “an unprecedentedly bohemian affair, and is a plausible starting point for London’s roaring twenties..”

It seems that Wadworth both celebrated and placed a punctuation mark after his service to the Royal Navy with a huge painting, Dazzle-Ships in Drydock at Liverpool in 1919, now in a Canadian museum, the National Gallery of Canada at Ottawa. To commemorate this work, the Tate Liverpool commissioned the Venezuelan artist Carlos Cruz-Diez to dazzle paint a vessel of the War era, the Edmund Gardner for the Liverpool Biennial. Revealed to the startled eyes of those who were unaware of the sheer brilliance of colors used by the dazzle painters, the Edmund Gardner, shone brightly in the brilliant summer sun on the 14th of July in 2014, an unexpected homage to the artists of black and white, Edward Wadsworth.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.