The E. 1027 House

The Architect as a Woman

The story of this building, innocently named E.1027, reads like a novel–with heroes, villains, vandalism, and victims. The beginning of this saga was ordinary enough, a famous designer decided to design and built a home. The extraordinary element was not the desire to have a home on the Mediterranean coast but the fact that the architect was a woman. Even in the early twentieth century, the term “woman architect” was not just a pejorative term but was also a contradiction in terms. The woman in question–to add insult to injury–was untrained in the field of architecture. To make matters worse, this house, identified by a letter and four numbers, was astonishingly brilliant..for a woman who was not even an architect. The fact that an extraordinary home had been designed by a woman, furnished by this woman with her original furniture designs, and that the structure presumed to rise up on a hill and look down upon the blue sea perhaps sealed its fate.

From the start, the provenance of this home was muddled. By 1929, Eileen Gray was fifty-one and was a well-established designer. Located on the Mediterranean shore at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, the house has no apparent access from either above or below and it tiered white structure sits alone, overlooking the Mediterranean Sea from a high vantage point, nearly invisible from those looking up from below. E.1027 would be the first of three houses she had designed. The house and the overall modernist design was probably the shared vision of Gray and her lover at that time, Jean Badovici, a Romanian architect. The name of the house marks out the collaboration: E for Eileen and 10 for J the tenth letter of the alphabet, 2 for B the second letter of the alphabet and 7 for G, combining the names of the architects. Even though both designers wanted a house in a modern, rather than the traditional Mediterranean style, the work bears the trademarks of Gray. She built E. 1027 for Badovici. Gray bought and paid for the land and the house, putting everything in his name. She followed his suggestion to erect the home on columns and to give it a flat roof, by now the standard vocabulary of modernist domestic housing. otherwise, it was she who camped out on the site for three years and monitored every aspect of its design and its construction. The original idea was for the two of them to live in the house but as many couples find out, building a house together often leads to a breakup and, in the end, Badovici occupied the home with a new girlfriend, while Gray went on to build her own home. She would feel the pain of the loss of this project for the rest of her life.

E-1027 Villa in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France

But E. 1027, even in its apparently romantic setting, was far more down to earth and much more personal than the typical home inspired by modern design. When the villa was completed in 1929, the pair had produced what amounted to a discourse on architectural design, based, not upon theory per se, but upon how people lived in a home and how the various rooms of the dwelling were used. As Gray explained, “Entering a house should be like the sensation of entering a mouth which will close behind you.” Their joint article in L’Architecture Vivante, which devoted a special issue to explaining this remarkable building. For example, in the article titled “Maison en Bord de Mer,” the architects explained that the doors to each room were placed outside of the sight lines so that each room appeared to be free and alone; inspired by the traditional architecture of the region and by the habits of the traditional women on the coast, the kitchen was separated from the house proper, the entrance experience was ambiguous with an atrium for the entry but upon entering the covered space, the visitor faced a blank wall and was forced to seek the entrance. The couple described the furnishings in detail including the use of a cork sheet on the glass-topped tea table so that the placement of cups and saucers would be silent. One of the more interesting words they used in describing the home was “considerate.”

Here, in E. 1027, a guest or permanent resident could find physical comfort, something that was often lacking in Bauhaus houses, and privacy and psychic peace were prized over open public spaces. One of the architects–it is disputed which one–designed doors and windows that could be opened, closed or adjusted according to the changeable climate on the Mediterranean Seaside. It is in the interior decor that Gray’s presence was most clearly felt. On the floors were her distinctive rugs, color blocked with abstract shapes, scattered in the rooms near her signature furnishings, the now famous Bibendum chairs, and familiar side tables next to beds and sofas. Throughout the home, from room to room, there is comfort and convenience and a meticulous attention to detail everywhere–Gray’s trademarks of mindfulness. Each piece of furniture was approached with an understanding not just of its customary and received function but also of the possibilities for facility and use. She created a small four drawer cabinet so that each drawer could swivel outward at a different angle, an innovation that meant that all drawers could be open and their contents accessed at the same time. A new chair, called the “Transat,” short for transatlantic, designed in 1925, appeared in E. 1027. Gray produced only twelve of these chairs, and nine still exist today: four were built in sycamore wood and the other five are lacquered. An homage to the deck chair on a transatlantic ocean liner, the sling seat was produced with canvas or pony skin or leather. This prototype chaise longue was ideal for relaxing with its low-slung design but also upgraded to elegance–if the occasion called for it–by shifting from humble canvas to more formal animal hide.

Perhaps because Eileen Gray’s furniture was not designed for mass manufacture but was elevated be extreme handwork or by a design that an unexpected turn, each of her designs was precious and unique. She probably never had a general audience in mind and certainly appealing to the larger public was not her goal. Gray had a tendency of think and create within a narrow intellectual band or certain artistic circles compared to her male modernist colleagues who wanted to reform the world. In many ways, the name of the house, E.1027, was, like her creative furniture, an inside joke of metamorphosis. The Michelin Man became a comfortable chair and the wooden deck chair, a rugged fixture on a ship, became cool and comfortable for life at the beach. As distinctive as her designs were, a work by Gray could be astonishingly flexible. For example, the most famous iteration of the Transat chair was part of a commission of 1931 for the Maharaja of Indore.

Bernard Boutet de Monvel. Portrait of the Maharaja of Indore (1934)

Maharajadhiraj Raj Rajeshwar Sawai Shri Yeshwant Rao II Holkar XIV Bahadur (1908-1961) arrived in Paris to ask prominent artists and designers and architects to design furnishings for his new modern palace in India, named the Garden of Rubies. Educated in England, the Prince went on a shopping spree, ordering from a diverse group, including the famed furniture maker, the traditionalist Jacques-Emile Ruhlmann, the modernist Le Corbusier, who was his opposite number and Eileen Gray who forged her own path. This remarkable collection of furnishings designed by the most famous artists of the era disappeared to Asia and was forgotten until the 1970s. The particular Transat chair commissioned by the Maharaja consisted of a black lacquer frame tipped in chrome details and a lounging sling of horizontal sections of brown leather. The top element for the head and shoulders is separate and attached so that it could be adjusted for comfort. This version of the Transat was that of a bedroom chair designed for relaxing or napping, rather than taking the sun on a beach house veranda or watching the ocean on rolling ship’s deck. In 2014, this version of the now famous chair sold for $1.5 million dollars.

The Transat Chair in the bedroom of the Maharaja

E. 1027 had its version of the Transat chair which was also placed in the bedroom, paired with the Bibendum. The original photographs show the chairs, which faced the low double bed, poised on a series of overlapping Gray designed rugs. The importance of looking at E. 1027 in its original state as recorded in black and white photographs is stressed because it can be clearly seen that behind the bed and to the right of the bed are plain white walls.

The Bibendum Chair (left) and the Transat Chair (right)

As is true of modern architects, Gray was comfortable with blank white walls as is seen when the back of the house is viewed. In contrast to the front of the house, which faced the sea, the of the sides and back of the home are plain blank solid walls, broken by a slice of narrow vertical windows.

The front of E. 1027 is designed with an awareness that it was seen by observers from above. E. 1027 rose on tall columns a full story above the ground with only a quarter of the structure—the entry—set on the foundation. Most of the exterior is broken up by a series of balconies and verandas, protected by canvas curtains, and all is open to the Sea. And again, even in the front, large segments of solid unbroken white surface sit comfortably. The exterior stair cases and the cantilevered elements speak for themselves, important contrasts to the stretches of white walls. But the spare design and open walls would be defaced, because once Gray moved out in the early 1930s, the house fell into the wrong hands. These harmful hands were those of Le Corbusier, who, for some reason, apparently became obsessed with a home he could not possess. His actions are hard to fathom. Le Corbusier and Gray knew each other and admired each other’s work, but something went very wrong. Unfortunately, in 1938 and in 1939, Badovici invited Le Corbusier to stay in this home. The architect was rumored to be jealous of Gray’s architectural achievement. Her design philosophy was directly opposed to his and to that of the other modern architects. “The poverty of modern architecture stems from the atrophy of sensuality,” Gray said in an interview in 1929 for L’Architecture Vivante. She stated that she was opposed to what she called “this intellectual coldness.” In addition, Gray remarked that “the machine aesthetic is not everything..” adding that “their intense intellectualism wants to suppress that which is marvelous in life.”

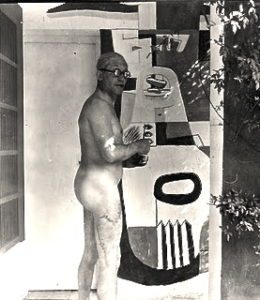

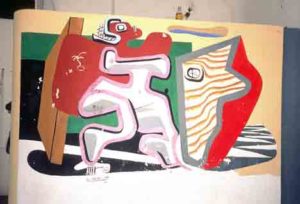

Nevertheless, Le Corbusier did not seem to take Gray’s assessment personally and when he first visited E. 1027 in 1937, he wrote to her saying, “I am so happy to tell you how much those few days spent in your house have made me appreciate the rare spirit which dictates all the organisation inside and outside. A rare spirit which has given the modern furniture and installations such a dignified, charming, and witty shape.” But in his next visit in 1938, as if to attack her work, Le Corbusier proceeded to paint a series of murals over every blank interior space he could find. Even in his best days, when he was still Charles Jeanneret, the architect was a mediocre painter and, in the 1930s, his style of painting was a truly uninspired pastiche of Picasso crossed with Surrealism in a mashup of garish colors. He settled into E. 1927 for a long and destructive visit and executed eight badly painted murals on every blank wall he could find on the inside of the home. In a 2014 article, Alastair Gordon wrote, “Between 1934 to 1956, Badovici had the house to himself and frequently invited Le Corbusier and his wife to visit. This is when the imposition, the so-called “rape” of the house began. There’s a group of grainy photographs, recently uncovered, that shows Le Corbusier lounging around the house in his underwear, or naked, or in pajamas. The snapshots must have been taken some time before World War II and there’s something vaguely pornographic and onanistic about the way he’s lying on the divan in the living room, touching himself, drawing something on a table while his foot is propped on a stool, or posing in front of one of the murals, further indicting himself.”

Certainly, it is true that Badovici, who owned the house, gave permission to the architect to paint the murals and presumably valued the results because, rather than painting the out, he preserved them during his lifetime. Gray was furious. How is one to judge such an act? The fate of many carefully designed buildings, created by famous architects, has ranged from unsympathetic remodelings to outright destruction, but there is something particularly unpleasant about the actions of Le Corbusier. First, the question could be asked—was what Le Corbusier did a deliberately sexist act? And this question can be answered with another question: is there another case in which one male architect painted over the work of another male architect? And, second these questions might solve a problem long puzzling historians, where did Badovici’s contributions end and Gray’s vision begin? Would Badovici have allowed Le Corbusier to vandalize his own work? One can suggest that, given the extent of the vandalism, which was all over the house, Badovici was not the principle author of E. 1027. To his credit, he did admonish Le Corbusier but did nothing to stop him or to remedy the situation.

The issue of sexism has been pursued even further because the murals by Le Corbusier were salacious, that is sexual in nature, and because he painted them in the nude. But the indignities that the house was to endure were only beginning. Two years later, the Germans occupied France and their allies, the Italians, moved into the home and enjoyed rowdy drinking on the verandas. Then the Nazis moved into E. 1027 and used Le Corbusier’s murals for target practice. After the War, Le Corbusier continued to stalk the house, writing Eileen Gray out of history by spreading the false information that it was Badovici who was the true builder. He insisted on living near E. 1027 and even built his own small structure nearby. When Badovici died in 1956, Eileen Gray loyally buried him, but when the Union des Artistes Moderne honored him, the organization excluded her from the credit for E. 1927.

Meanwhile Le Corbusier arranged for the home to be sold to a woman described as “wealthy” “Swiss” and a “woman.” The house had been empty for four years and Le Corbusier instructed her to keep the house as it was, murals and all. Unhappy with the rundown condition of the home, she turned it over a drug addicted doctor, who sold off Gray’s valuable furniture. Gray herself was forbidden to enter her own former home and her own work of art. Le Corbusier watched over the house he never owned and in 1965, fate caught up with him. Now in old age, he was an overweight alcoholic, ill-suited to athletic pastimes. While swimming in the Mediterranean Sea in front of the white house high on the hill, he had a heart attack, dragged himself to the shore and died. In 1956, the drug addicted doctor, who gave wild parties, was murdered by vagrants on the premises. As would happen when in the hands of an addict, the house was in a state of disrepair and was abandoned after his death. For years, off and on, squatters were the main residents of E. 1927. Finally, in 1975, because of the murals by Le Corbusier, the house was considered worthy of preservation by the French government. A year later in 1976, Eileen Gray died. She did not live to see the beautiful restoration of her masterpiece, murals and all in 2015, nor did she live to see the name “Eileen Gray” resurrected and respected.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.