Eileen Gray (1878-1956)

Art Deco Furniture Design

If Cassandre gave the Jazz Age its distinctive graphic style, then it was a woman, an architect and a designer who gave the decade its most memorable piece of furniture, still in production today. The E. 1027 side table, designed in 1927, is one of the few objects from Art Deco that is ageless and timeless and transcends its period and is still sold as “modern” furniture. The chrome frame does an efficient double duty–the lower level, an almost-closed circle, and the upper circle, elevated by a verticle slide that allows the height to be adjusted, is filled in with glass. The design is simple geometry–two circles and two straight lines–elegance in and of itself. The ingenuity of the operation, cleverly concealed and modestly articulated along the verticles, allows the table to be raised or lowered according to the height of the accompanying piece of furniture. This bent tubular steel table dates from 1925, coinciding with similar work by Mies van der Rohr and Marcel Breuer. Like Gray’s Bibendum chair, the table is made of circles, one at the top, a circle of bent steel topped with glass and at the bottom there is a broken circle as the base of an adjustable table that could be slide under a bed or pushed near a chair. The two circles are held together by an elegant long thin rectangle. The height could be adjusted with an elegant chain attached to a pin which can be slotted into the desired hole so that one could use it as a side table or as an over the bed table for having breakfast or an afternoon tea. The famous side table is one of those rare products that has never been altered. Indeed, in her own right, Eileen Gray was a rare individual in those days—a woman who became successful in fields that were owned by males: art, design, and architecture. The entrance of a woman into the field of architecture during the early decades of the twentieth century would be considered an effrontery to her male peers, but perhaps because she was an outsider, Eileen Gray simply walked into the discipline without any formal training and designed one of the most famous houses of the twentieth century, the E1027, after which her famous table is named.

E. 1027 Adjustable Side Table

Eileen Gray lived in multiple worlds, shifting with ease between the domain of the arts and the terrain of the wealthy, the class to which she was born. During the Jazz Age, Paris was one of the cultural centers where lesbians were allowed to live openly and productively, contributing to society with literature and art. As a member of the group of creative women, Gray was wealthy enough to accessorize her Garçonne look with elegant coats designed by Paul Poiret and stylish hats by Jeanne Lanvin that covered her short bob. The fashionable designer roared around Paris in a fancy car, accompanied by one of her lovers, the singer, Marie-Louise Damin, known as “Damien.” Damien owned a pet panther, who rode in the back of the car.

One of the modern artists of lacquer, the Irish artist learned of lacquer while she was a student at the Slade School in London. In 1900, according to her biographers, Jennifer Goff, Gray found a display of lacquer first at the Victoria and Albert Museum and later at the shops in SoHo, where she found a restoration shop on Dean Street. The owner Dean Charles took her on as a pupil. Two years later in 1905 Gray, resumed her education with the restorer. Discussing the 1688 book, A Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing, Goff wrote that “Gray would eventually import all of her pigments from China. The colors which were popular in the manual included ivory black, lampblack, verdigris, umber, indigo or yellow ochre. The manual advocated the use of only the best varnish which also could be used for varnishing light colors such as white, yellow, green, sky red, silver or gilded. A black ground was advocated, through grounds could also be, though rarely, white, which in the seventeenth century imitated porcelain.” This last sentence was interesting in its reference to the color white and the rarity of its use as a ground color, for some of Gray’s most famous work of the 1920s would be in white. From London, Gray traveled to Paris to continue her training in the difficult and labor-intensive craft of lacquer working.

Using her early work as an introduction, Gray apprenticed herself to the Japanese lacquer artist, Seizo Sugawara, a man as young as she was. Thanks to this specialized training, she was part of a modern revival of this ancient art form. For years, partnering with Sugawara, Gray perfected the demanding methods of producing perfect lacquer pieces. As Goff pointed out, as early as the turn of the century, France had been involved in an arts contest with Germany, which was especially strong in crafts and design. Thanks to the government’s interest in competing with an old foe, designers felt emboldened to form a Société Nationale des Artistes Décorateurs to promote themselves and their art. In this pre-war period, the Sociéte was a precursor of the Bauhaus in its concern with industrial design. After the Great War, France resumed the competition with other nations in the world of modern design and it was in the year of the famous exhibition, the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in 1925 that Gray joined the Société. The moment of modern Art Deco design had arrived, and, although the design achievements of this period discussed in traditional art history texts tend to be limited, the twenties was a golden age of design innovation. In a nation that used lacquer only for conservation purposes, this resurgence of an ancient craft attracted the attention of well-heeled clients and Gray herself became an established designer who specialized in the painstaking craft of lacquer which she transformed into a stunning art form. As the Phillips auction house noted, “Gray was devoted to Asian lacquer, which she first encountered in 1900 as an art student at London’s Slade while wandering the halls of what is now the Victoria and Albert Museum. From 1908 she worked in the medium with mentor Sugawara, originally a maker of Buddhist lacquer shrines. Whereas her modernist peers advocated a rejection of timeworn methods, Gray embraced those traditions, lacquer paramount among them: it grounded her high-flying experiments in form.”

In the years just before the Great War, Gray, now well known for her unusual art, acquired the French designer and art collector, Jacques Doucet, as one of her new clients. Doucet was at a turning point in his life and he suddenly decided, in 1912, to sell off the 18th-century contents of his 18th-century apartment and to become avant-garde. The story of the Doucet about-face is one of the legends of stylistic change. In 2014 Louis Bofferding wrote for Architectural Digest that “Eighteenth-century French antiques defined the taste of the Belle Epoque, and Doucet joined the throng. He commissioned society architect Louis Parent to build an 18th century-style mansion, completed in 1907, on rue Spontini in the 16th arrondissement. With the aid of Georges Hoentschel, the influential decorator-dealer, Doucet then conjured interiors replete with exquisite treasures.” In fact, Doucet had been collecting eighteenth-century furnishings for decades and this home was expressly built to display his treasures. And then something remarkable happened. A mere five years later, Doucet suddenly put his entire collection on the auction block, and, in a four-day extravaganza, the buying frenzy made him the equivalent of seventy-five million of today’s dollars. The auction was apparently an act of mourning on the part of the famous dress designer, grieving over the death of a woman he planned to marry. However, Doucet recovered and purchased a new home on the avenue Foch. Turning his back on the past, he hired the most trendy designers from Paul Iribe to Eileen Gray to design the furnishings. Apparently inspired by this new start in modern Jazz Age surroundings, Doucet married a younger–much younger–woman.

But it was his librarian future Surrealist André Breton who persuaded him to purchase Picasso’s painting, Les Demoiselles d”Avignon (1907). This painting had spent most of its life rolled up under the bed of the artist and had been shown publically only once, in a 1916 exhibition during the Great War. In 1924, Doucet purchased the now famous painting, which was eventually installed at his wife’s home. In 2004, Les Demoiselles, now at the Museum of Modern Art, was cleaned. According to The New Yorker,

John Elderfield thinks that Doucet’s restorer may have varnished “Demoiselles,” whose installation, on a landing at the top of a grand staircase in Doucet’s apartment in Neuilly-sur-Seine, left it somewhat vulnerable to bibulous dinner guests. There is no doubt that it was varnished, or revarnished, in 1950, by a conservator at moma, which had acquired the painting in 1939. “I do think it was done with preservation in mind.” James Coddington, the Museum’s chief conservator, said tactfully, “but in fact that doesn’t necessarily preserve it. This is a classic, robust, straightforward oil painting. Picasso used really high-quality paint, and he was very good in his craft. To remove a varnish does expose the picture to potential hazards.”

Much more compelling and modern, however, was his commission of an unusual work by Marcel Duchamp in 1924. The Rotative Demisphère, is one of his machines, a revolving disc inscribed with a spiral, which, once set in motion, gives an art viewer something to look at. “Olfactory art,” as Duchamp termed traditional art, was merely attractive, an act of good taste that nourished the senses and not the mind. Therefore, Duchamp argued one might as well look at a spinning line for all the intellectual nourishment “art” gives.

Sadly, Doucet had little time to enjoy his acquisitions. Just a few months after the apartment was completed, Doucet died in 1929. It has been said that his wife tired of the relentless gazes of the implacable five nudes, Les Demoiselles, glowering from the top of the stairs and sold the painting to the Museum in 1939.

Les Demoiselles d”Avignon (1907) at the top of the stairs

at 33 rue Saint-James, Neuilly-sur-Seine

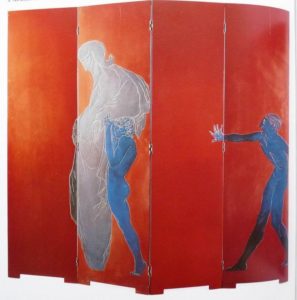

An Irishwoman in Paris, Gray was a successful businesswoman, creating products for an aristocratic clientele and group of collectors. Part of running a business meant advertising her wares, which, in that period, would be done discretely in sites such as the 1913 Salon des Artistes Décorateurs, where Jacques Doucet saw her screens. During this period, Gray went beyond mere pattern or decoration and created narratives with mythological and mystical themes played across her screens. Competing in the heady company of Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Amedeo Modigliani, and Picasso, Eileen Gray contributed several pieces for the new décor for Doucet’s new decorative project, including a remarkable example of what was, at that time, her signature work, a red four panel lacquered screen, Le Destin. Doucet also commissioned several of her most famous earlier works for his new home. The Table modèle bilboquet is usually dated between 1915 and 1917. This premodern work is an early version of the E.1027 table in that it also is composed of two circles, one at the top and one at the bottom, both supported by four squared off legs, made of an ensemble of multiple wooden squares. The bilboquet in question is a simple game for children. The skill involved consists of a ball attached to the stick with a cord. The handle has a cup at the top and the ball is released from its perch, still on its leash, and is caught by the cup. The game is illustrated on the edge of the black lacquered top in red and silver, at the client’s request.

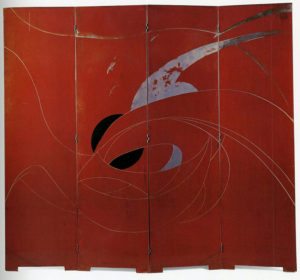

When Doucet came to Gray’s studio, she was working on a symbolic theme, Le Destin, which the collector understood to be a work of art and demanded that she sign the screen as a painter would sign a painting. Gray and Doucet came together at the height of the pre-war surge in design in which artists were stretching beyond Art Nouveau and searching for new modes of expression. Many examples of Gray’s work that were displayed at the Doucet homes were from the pre-war period or were made during the War itself. Le Destin, completed in 1914, the brilliant red folding screen, sold to Doucet, showed two silver and blue men, drawn in the style of a Greek vase on the front, while the back was a swirl of sharp cut curves, with some arcs filled in with slices of black and silver.

Gray, who was widely read, found inspiration as much from literature as from works of art. While this pre-war period of her early work can be described as the end-point of Art Nouveau because each piece of furniture was a unique exquisite work of art, the beautiful Lotus Table, also made for Doucet, was obviously inspired by Egyptian sources. Moreover, this unique green lacquered table with its golden lotus legs was distinguished by four hanging black cords ending in green tassels, topped by red beads, was designed over a decade before the discovery of the tomb of King Tut in 1925. The red lacquer Charioteer Table, which dates to the same year as the red screen, stood in the entrance foyer of the Doucet home at the bottom of the stairs. A floor above, Les Demoiselles loomed.

During the pre-war period, Gray custom-made, with her own hands, each and every piece of furniture for wealthy clients, giving herself unsparingly to perfection, no matter how long it took. This artist-crafted quality meant that each piece of her furniture is a work of art that was exclusive, non-replicable and non-repeatable, adding to the exquisiteness of her products. Sadly, few of these remarkable works of art are extant. During World War II, much of what she had made was warehoused in Toulon but the site was bombed and the art was destroyed. The Doucet collection is not only all the more precious because of this loss but also because the Great War interrupted the artwork of Eileen Gray. Gray returned to England in 1915, taking Sugawara with her, and even drove an ambulance as her contribution to the war effort. In London Gray would be exposed to a new form of Cubism or its antithesis, Vorticism. The further discussion of her artistic development will be discussed in the next post.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.