POSTMODERN THEORY

Introduction: Modernism and Post-Modernism

Deeply marked by the idealism of the Second World War, Americans woke slowly to the changed landscape where idealism was impossible. The era of endless fear and war without end had dawned. The only way it could be borne was that this war be fought somewhere else. The importance of importing Euro-American nationalistic antagonisms to the Asian and African continents cannot be overestimated, for the Cold War provided a theatrical drama for political posturing while the audiences could recover at their leisure from the wounds they had inflicted upon themselves. For Americans, these little disfiguring wars were played out on television, but for those who actually participated, the pain and death were quite real. Colonialism continued, empires lived on, relics of a bygone time. On one hand, the former colonialists could relish, with a certain sly malice, the post-colonial difficulties of heretofore stable governments–India and many African states–after colonial masters exited. But, on the other hand Euro-American economic interests could and had to be protected in the name of freedom and democracy in nations fortunately enough to be favored in terms of valuable natural resources.

After the misadventure of Viet Nam, America would not intervene unless the territory had something to offer. Otherwise the “Free World” would look the other way from genocide and massacres and famine and internecine wars. The rise of what Eisenhower called the “military-industrial complex” drew the Soviet Union into an economic race of guns and butter that the communist nation could not win. By 1989, the Cold War was over and the “Evil Empire” collapsed, the Berlin Wall fell and Eastern Europe fractured into ethnicities that attempted to exterminate each other in the wake of the Fall. Left behind were the weapons of the Cold War: countless nuclear weapons capable of Mutually Assured Destruction or MAD that spelled the end of rational modernism and the dissolution of the promise of the Enlightenment. It is interesting to note that the seemingly endless stand-off between good (capitalism) and evil (communism), strangely based in economic systems, masked with pseudo morality the larger moral failings of the Second World War.

Postmodernism is often considered to be a time of lost idealism, lost faith, and, most of all Loss of Mastery. This “post” period also coincides with the end of the old military industrial technology and the beginning of a cheap and seemingly unstoppable information technology. At best the new computer-based technology makes information available everywhere and makes present and future Iron Curtains useless in the long run, suggesting a future of human self-determination. At worst, the same technology promises to enlarge the gap between the rich and the poor, between developed and developing nations, between those who can afford the precious commodity of information and those who cannot. Information technology privileges the cultures that own and control it and that can thus spread it globally, at the expense of local ethnicities and identities. Information technology also privileges the mind and the talents of the intellect, suggesting that age-old requirements of race and gender will become irrelevant and that globalization will also mean human pluralism. The interesting question is how those in power will manipulate a volatile and unprecedented event–the Internet–to remain in power..and they will, setting the stage of another conflict between individual self-assertion and uncontrollable government control.

Within this historical context, Post-Modernism seemed to punctuate the end of yet another long century that was on the brink of the Information Age. Postmodernism was thought of as the contemplation of the end of the Industrial Era in economics, the end of Enlightenment in philosophy, the end of world empires in politics. From the perspective of a historian of art, these ends of centuries are often characterized by periods of sheer academicism and artistic ennui and a critical waiting for some kind of aesthetic Messiah, like Jacques Louis David or Vincent van Gogh. Post-Modernism, then, could have also been the End of Modernism, awaiting what’s next. Like the Post-Modernists, French aristocrats, indulged themselves in idle amusements at the end of another century, lived unwittingly just prior to an event, a state of mind, a way of life, that would be called the Modern or the Enlightenment. It is apt that it was the French Revolution which ended their century and their way of life began the Modern era, because this Revolution, like Modernism, sought to end all history, to erase the past, to efface all tradition, all heritage, and all values. As Ihab Hassen wrote in “Towards a Concept of Postmodernism” in 1987, “The word postmodernism sounds not only awkward, uncouth; it evokes what it wishes to surpass or suppress, modernism itself. The term thus contains its enemy within..”

Now that we are well into the 21st century, it is possible to view Postmodernism as a brief period, lasting about twenty years that is now best known as a changing of the guard in the visual arts. For the generation of Jackson Pollock, the canvas was an existential arena of self-creation and self-expression, a place where art–act–and the artist could become one in a transcendent moment of being and creation. For Pollock’s generation, the key words would be authenticity and personality. The work of art was unique because the personality and the touch of the artist was unique, his or her signature that authenticated the work itself. This high-minded hope, later called the “pathetic fallacy” (the notion that one can read the emotions of another emphatically through art is a fallacy), was swamped by the onslaught of pre-given, pre-digested, pre-created, and pre-conditioned media images. In his 1986 essay “Mass Culture as Woman: Modernism’s Other,” the postmodern theorist Andreas Hysseun stressed the importance of separating modernist art from “low culture:”

Modernist literature since Flaubert is a persistent exploration of and encounter with language. Modernist painting since Manet is an equally persistent elaboration of the medium itself: the flatness of the canvas, the structuring of notation, paint and brushwork, the problem of the frame. The major premise of the modernist art work is the rejection of all classical systems of representation, the effacement of “content,” the erasure of subjectivity and authorial voice, the repudiation of likeness and verisimilitude, the exorcism of any demand for realism of whatever kind. Only by fortifying its boundaries, by maintaining its purity and autonomy, and by avoiding any contamination with mass culture and with the signifying systems of everyday life can the art work maintain its adversary stance: adversary to the bourgeois culture of everyday life as well as adversary to mass culture and entertainment which are seen as the primary forms of bourgeois cultural articulation.

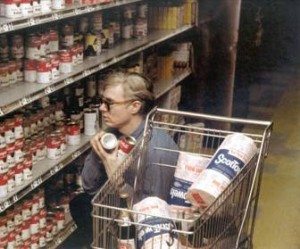

The fall of Modernist singularity and the rise of a self-referential culture starts with the coming of age of the Baby Boomers in the sixties. The star of Pop Art, Andy Warhol did not bother to create himself through the existential process of art making, instead he presented/displayed himself as an “art star,” as a cultural icon, as a media darling. Warhol, once the most successful commercial artists in America, understood the power of advertising and the significance of the image very well. He understood that art was a commodity to be bought and sold and that the commodity would be read as ‘art” if it was made by an “artist”. With some difficulty, Warhol remade himself in the image of his own time, created the aura of “artist” by fitting himself into the prevailing art movement, Pop Art. He crafted an image of the eccentric and colorful artist, a celebrity among celebrities. Warhol is an artist equally, if not more important, than Pollock, for like Pollock, he and his art came to exemplify his time. As Huyssen argued in “Mapping the Postmodern,”

..the revolt of the against that version of modernism which had been domesticated in the 1960s was never a rejection of modernism per se, but rather a revolt against that version of modernism which had been domesticated in the 1950s, become part of the liberal-conservative consensus of the times, and which had been been turned into a propaganda weapon in the cultural-political arsenal of Cold War anti-communism. The modernism against which artists rebelled was no longer opposed a dominant class and its world view, not has it maintained its programmatic purity from contamination by the culture industry. In other words, the revolt, the revolt sprang precisely from the success of modernism, from the fact that in the united States, as in West Germany and France, for that matter, modernism had been perverted into a form of affirmative culture.

Pollock may be the American artist who “broke through” the European hegemony of the arts, but he was also the last of his kind, an artist of the old school, concerned with craft, creation, process, and expression in the naïve belief that genuine creativity was possible. If Pollock was the Last Modernist, then Warhol is one of the first Postmodernists, for he frankly abandoned the pretense of originality and made a career out of appropriating the ready-made images already available commercial culture. The importance of Warhol lies, not in the fact that he introduced objects/signs from everyday life or popular culture into the art world, but that he did so in such a way as to both replicate the technology of multiplicity and to reproduce art “like a machine.” Warhol immersed himself in the media world and at the same time provided cogent if elusive commentary on his environment. His encyclopedic art seemed to assert that ee are all canned and packaged; and our role models and idols are all also canned and packaged.

Andy Warhol Shopping

Representation, after Warhol, could only mean re-presenation: to show again that which has already been manufactured according to pre-given specifications. And this re-presentation, therefore, can never be original. Re-presentation, because of the every-where-ness of media technology can only be an artistic re-action, never an existential act, only an artistic critique, never an artistic creation. That was the condition of the artist in a postmodern technological society in which images are provided for consumers. From the postmodern perspective, the artist can no longer create images, the artist can only respond–belatedly–or philosophize or ponder what it means to live in an image world. This realization that “originality” was but a myth is the foundation of Postmodernism. Postmodernism was built upon the un-building of the innocence of Modernism, and, like the art of Warhol, was entirely reflective of the disillusionment of the Sixties and Seventies in the face of revelations of racism and sexism in America and the involvement of the Land of the Free in a war that proved to be largely political—Vietnam—and the fall of Presidents into disgrace and national shame.

In the visual and performing arts, Modernism was also a Revolution, a new beginning and a new awareness of being in a new place that ironically always had to be re-placed by yet another new, another now, until regeneration could no longer take place and exhaustion–Post-Modernism–reigned. If the decade of the Sixties can be seen in retrospect as the dawn of the breakdown of the hegemony of Modernism, and the decade of the Seventies as the puritanical revolt against physical attraction in art, then the decade of the Eighties seemed to be at the end of all things. Painting was declared dead and was condemned to endlessly copy or comment upon itself. Sculpture had expanded beyond itself and had left the gallery only to return as installation. Photography became the leading Postmodern art form because of its inquisitive ability to both question and expose the limits and transgressions of Representation. The aspirations of Modernism, its high moral tone, its very spirituality was confined to art-dealer nostalgia and put to shame by Postmodern irony.

Art–now a commodity to be bought and sold like a stock or a bond–was reduced to desperate discourse, parading bravado shorn of originality. Art copied. Art replicated. Art looted–pillaged–plundered history, like a frantic army, devouring its own past in its ignorance of the future, scorching its own earth. Above all else, art, haunted by the economic boom and the economic bust, was relegated to the status of decoration in the name of tasteful investment that killed the painter Jean-Michel Basquiat in 1988. The death of Basquiat was a marker that suggested that the art world was no longer based upon its supposed “human values” but had, instead, entered into a global market where commodities circulated endlessly in an impersonal system of exchange. By the end of the eighties, Postmodernism was a global and Western phenomena: the European version of Postmodernism and the American version of Postmodernism had become absorbed into a larger culture, driven by the forces of capitalism. Cultural distinctions, like the use of elephant dung by the British artist, Chris Offili, could easily be taken over and become part of the mainstream and marketed to collectors as the latest “Sensation” in global art.

Although Postmodernism was a product of the times, the movement, when viewed in the simple terms of art world credos, was another look at the blind spots of Modernism. One of those lacunae was the art of Marcel Duchamp whose art co-existed with Modernist art and yet was its silent underground. More than a Dadaist “anti-art,” the postmodern portents of Duchamp were an anti-reading of Modernism. Known to day as the “Father of Postmodernism,” Duchamp undermined the foundations of Modernism: eliminating the independent and inventive artist who “made” unique “objects,” and subverted the doxa of “original” art made by a sanctified “creator.” His ideas were not understood in their own time and were mi-translated in the Postmodern period, but he predicted the unraveling of a system of art based upon the impossible and imaginary edifice of art elevated above the real world, floating pure and free of the market and financial interest. Whether one argues that Duchamp “fathered” postmodernism because he laid the groundwork for the revolt against Modernism or because his once-alien ideas fell on ground fertilized by Fluxus and other post-war impulses, it can be said today that Duchamp’s greatest success was in drawing the line between representation and concept. The arts of the Postmodern and the 21st century would fall on the side of the concept.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.