FREDERIC JAMESON (1934-)

Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1984)

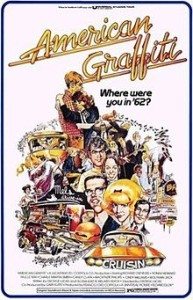

Two In Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1984) Frederic Jameson (1934-) examined film and architecture as forms of postmodernist culture that displayed the marks of the “waning” that was the Postmodern. Examples of this “early” postmodernism, that is, postmodernism avant la lettre, can be found in films made by Hollywood in the early 1970s and early 1980s. As a neo-Marxist theoretician, Jameson termed these films “nostalgia films” created out of collages of drifting memories of past times and of past films which were then pasted together into a pastiche of other films, half remembered. It is important to pause and take note of the collective ages of the Baby Boomers for whom these so-called “nostalgia” films were made and marketed. The age of the viewers would have been thirties and forties and it is their knowledge of popular culture that is put into play. Depending heavily upon the adult audience’s cultural memory of Hollywood, movies, such as Star Wars (1977), Grease (1978), Chinatown (1974), and Body Heat (1981), became the leading examples of a trend of cinematic intertexuality that would become the foundation of later works, also based upon intertextuality, such as, Pulp Fiction (1994) and L. A. Confidential (1997). Jameson referred to a phenomenon he called the “waning effect,” or the impact of the commodification of objects in which movie stars are commodified into their own images, a condition that Andy Warhol understood quite well, displaying Troy Donahue with the same indifference he lined up cans of soup. Postmodern works, whether early predictions of the breakdown of Modernism suggested by the works of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, or later manifestations of actual Postmodernism, such as the referential photography of Jeff Wall, are all conceptual examinations of what makes a work of art see-able and recognizable to an audience with a rich collective memory of both high and popular culture. In the process of exploring a trail of quotations of earlier works, these artists made the familiar unfamiliar and uncanny, by revealing the means of the making of “art” as a concept. Jameson understood that (postmodern) “theory” had become a new kind of (nostalgic) discourse and that Postmodernism is marked by a sense of an end of philosophy and as Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man (1992). In redeploying Marxism as the new neo-Marxism of Theodor Adorno (1903-1969), Jameson straddled the divide between the Cold War and the Fall of the Berlin Wall, where, as Fukuyama put it, history ended. Therefore in the essays, “Postmodernism and Consumer Society” and “The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism,” Jameson defined Postmodernism in Neo-Marxist terms. For Jameson, Postmodernism is not a style but a periodizing concept that is correlated with the emergence of a new kind of social life and a new kind of economic order: modernization in a post-industrial consumer society. Following the Frankfurt School, Jameson combined philosophy with political science and sociology and literary criticism and, as were Adorno and Walter Benjamin (1892-1940), also concerned with the society of the media and the spectacle in an age of multinational capitalism. Most observers would agree with Jameson that the 1960s was the critical period, the break with Modernism, which ushered in two new and significant features in mass media: pastiche and schizophrenia. American Graffiti (1973) an early nostalgia film by George Lucas Pastiche is compared with parody, which is possible only when the artist can play off a prevailing style in order to mock the original and to ridicule its mannerisms. Parody is based in a belief in a norm, such as Andy Warhol’s parody of the pretensions of Abstract Expressionism. But when there is no belief in “normal language,” as in Postmodernism, art becomes fragmented and privatized with each group of artists speaking in a private language called “theory” of art or art commenting upon art. For example, in the art world, Pluralism followed upon the demise of the “last official style,” which was mid-1960s Minimalism, and it was the seventies that ushered in an age of pastiche. In this era of stylistic diversity and heterogeneity, pastiche appeared as an imitation of a particular and unique style but wore a stylistic mask. Pastiche speaks in a dead language and is supposedly neutral. One could return to Friederich Schiller (1759-1805) and revisit his concept of satire, which was one of the tools of Schiller’s “sentimental artist,” who is always detached and alienated (like the Postmodern artist). Pastiche is blank parody and blank irony, without a sense of humor (unless the humor is black, as in Pulp Fiction). Art is about itself but in a new way. This is not “art for art’s sake” but a sign of failure of art as an aesthetic of the new. Art can no longer be defined as an aesthetic of the new. Within Postmodernism, stylistic innovation is no longer possible. All that is left to do is to imitate dead styles and to speak in dead languages. Schizophrenia is a reflection of the radical break in time and space between Modernism and Postmodernism. Classical Modernism was an oppositional art–opposed the established art forms or opposed to the prevailing ideology that could be both a scandal and offensive to the public as with Dada. Today, the provocative challenge of Modernism to reality is taken for granted by the art institutions and the art public and all subversion is co-opted by the established order. Contemporary art has shifted its position and is now fundamentally in and part of our culture and can no longer exist outside of the system, as art becomes a commodity production linked to styling changes. With no future “shock” to move towards (because everything and anything “new” is immediately commodified), then art can only recycle, reuse and repurpose. Time folds back upon itself. Without a sense of past and present and future, the sense of history disappears and there is a loss of capacity to retain our “own” past as life that is lived in the perpetual present. Perpetual change obliterates traditions and transforms reality into images and time is fragmented into a series of perpetual presents in the plural. In this existential present, the past becomes a referent and an opportunity for formal inventiveness. As Jameson remarked, Edvard Munch’s painting The Scream is, of course, a canonical expression of the great modernist thematics of alienation, anomie, solitude, social fragmentation, and isolation, a virtually programmatic emblem of what used to be called the age of anxiety. It will here be read as an embodiment not merely of the expressionism of that kind of affect but, even more, as a virtual deconstruction of the very aesthetic of expression itself, which seems to have dominated much of what we call high modernism but to have vanished away–for both practical and theoretical reasons–in the world of the postmodern. The very concept of expression presupposes indeed some separation within the subject, and along with that a whole metaphysics of the inside and outside, of the wordless pain within the monad and the moment in which, often cathartically, that “emotion” is then projected out and externalized as gesture.. The past can be approached only through stylistic connotation of “pastness” or glossy qualities of image-as-fashion. The intertextuality of Postmodern art is deliberate and built into an artificial “aesthetic effect.” The result is a “history of aesthetic styles” that replaces the “real history” of art. The aesthetic then becomes a sign and these signs program the spectator to recognize the appropriate “nostalgic mode of reception.” This pastiche of a past that has been stereotyped causes a “crisis” in historicity because the subject has lost the ability to recognize or to organize past and present into a coherent experience. Schizophrenia is a breakdown in the signifying chain, creating a rubble of distinct and unrelated signifiers: a linguistic malfunction. This schizophrenic disjunction is a form of écriture–writing–or a cultural style. Therefore, Postmodernism cannot be a style and can only be a cultural dominant that is oppositional to Modernism and confronts the modern movement as a set of dead classics. The familiar depth model of Modernism is replaced by textual play and multiple surfaces, meaning that the cultural language is now dominated by categories of flat space, rather than categories of time or history, chronological or temporal categories. With the disappearance of the individual and the consequent unavailability of personal style, pastiche reigns as a dead language, an imitation of dead styles. Postmodern pastiche is speech through masks or voices culled from the imaginary museum of global culture. Pastiche foregrounds practice and orchestrates the primacy of historicism as a random cannibalism of the styles of the past recycled into “neo” or a “simulacrum,” as Jean Baudrillard said, an identical copy for which no original as ever existed. The “Neo-Noir” film is a simulacrum of “Noir” movies, which were highly artificial and stylized morality tales from the American film industry of the 1940s and 1950s. The black and white image of Noir was recycled into the “Neo-Noir” film in color and is an image of an image and, according to Jameson, is the final form of commodity reification. It was the French, starved of American films during the Second World War, who discovered these crime movies, considered B movies and named them “noir” films and created them as a particular genre. The French noticed the return of the Le mode rétro, or nostalgic film, as a restructuring of a pastiche of films made decades ago, a time long gone by, the time of the parents of the Baby Boomers. These nostalgia films were projected into the collective and social level in an attempt to appropriate a missing past of an era lost in time. Follow the discussion in Parts One and Three. If you have found this material useful,please give credit to Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.Part