AFTER THE GREAT WAR

John Heartfield: The Social Critic

One might ask, if there was a Third Reich, when were the first two Reichs and where does the Weimar Republic fit in? It’s an interesting question because in answering it, one comes to realize that the Republic is an odd, and perhaps, doomed interval, wedged in between centuries of absolutist regimes. The First Reich, which was never called the “First Reich,” only the Reich or the kingdom, was the revived Holy Roman Empire, brought back to life first by Charlemagne in 800, according to some. But other historians date the beginning of the First Reich by Otto I. By the middle of the tenth century, Otto had managed to bring much of northern Europe under his control. His military might and territorial domination meant that Otto was the temporal equal to Pope John XII, who needed the King’s protection. In return for the mutually beneficial partnership, the Pope crowned Otto the new Emperor of the now “Holy” Roman Empire in 962. At its peak, Otto’s Empire stretched north to south, from the North Sea, reaching down to absorb all of Italy, with the exception of the Papal States. Setting a precedent that would last for centuries, Otto I was strong enough to later depose John, install his chosen Pope, and take over the “holy” aspect of the Empire by controlling the Papacy. Otto II and Otto III, the son and grandson of the first emperor, used the title “Emperor” and their successors carried on the tradition of deciding who should be Pope for hundreds of years.

The title passed from family to family, through advantageous marriages: the Hohenstaufen and the Habsburg families ruled until modern times. For a thousand years, this Reich, which officially became “German” in 1452 and called the Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation. Under this new designation, the Empire continued for four more centuries, only to finally be dissolved during the Napoléonic Wars in 1806. By that time, the capital of the Reich, a shell of its former self, was located south and east of the Germanic states, in Vienna; and out of this dissolution, the embryonic modern Germany began to emerge. It was Napoléon who divided the Germans from the Austrians and turned the Germans into the Confederation of the Rhine, a geographic and governmental creation, later ratified by the congress of Vienna. Emerging from the shards of the long-dead Empire, this Confederation consisted of a cluster of thirty-five monarchies and four free cities. The Deutscher Bund or German Confederation was dominated by Austria and Prussia, and the two powers vied with one another for power well into the nineteenth century. The prolonged struggle between two German-speaking cultures held back both the modernization and the consolidation of both sides. While England and France were building overseas Empires and significant navies, the Germanic factions wrestled with each other, intent on establishing internal European “empires,” to dominate north-eastern Europe. The Seven Weeks War of the mid-1860s ended with Prussia, under the leadership of Otto von Bismarck, vanquishing Austria. Prussia rose out of a long power struggle as threateningly militaristic and ambitious to expand, anxious to catch up with the nations seen as its new rivals. In less than ten years, Prussia subdued France, ending the Napoléon III’s Second Empire with the French surrender in 1871. In an act designed to humiliate France, Germany, the modern state, the Second Reich, was declared in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, the former palace and home of the French kings.

George Grosz. The Engineer Heartfield ()

A united Germany, seeking “living room,” was a danger to Europe and the older powers kept wary eyes on this possible adversary. These mutual animosities almost certainly led to the disastrous Great War, a war into which Russia, Italy, France, and England fell, pulled down by the gravity of German desire to rule. The Second Reich ended when German finally recognized it could fight the Great War no longer and surrendered to the Allies. The Armistice in 1918 and the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm in November was the final and complete end to a short and ill-fated empire. A full thousand years under some form of autocracy and absolute rule had passed and suddenly, by Treaty, Germany was transformed into a Socialist Democratic Republic, an utterly alien political condition for the German people. The Weimar Republic lasted less than two decades and was wiped away by the Third Reich under Adolf Hitler who was “elected” in 1933. Hitler’s dream of another “Thousand Year Reich” was a mirror image of the First Reich, started by Otto I. It is also interesting to note that, less than a century after the Seven Weeks War, an Austrian once again ruled the German speaking people.

The Weimar Republic, a coalition government, was threatened from within and destabilized by the Allied powers from the very beginning. Unused to self-governance, the German people were locked into left-wing and right-wing power struggles politically, while the Treaty of Versailles saddled the nation with crippling reparations that had to be paid back. While the new nation fought to survive frequent incursions from the vengeful French, the sudden freedom from a repressive Empire allowed a surge of creativity in the arts. Under the most unlikely of circumstances, a new and modern cultural blossomed under what was surely a pale and baleful light. Minds now liberated from censorship, lives that had once been stunted by social disapproval enjoyed free reign, as Berlin became the European capital of sexual freedom, open to all tastes and needs and proclivities. Artists were allowed a certain level of freedom of expression, but the insecure Weimar Republic kept a wary eye on restive artists who dared to be too critical. And the most critical artists, whose sharp eyes and cynical minds, honed by a Dada sensibility, were the old friends John Heartfield (1891-1968) and George Grosz (1893-1959). They could not have foreseen the future, a period when the political unrest would prove to be the proving ground for a dangerous group of thugs, who would style themselves in elegant uniforms as “Nazis.” They attacked what was in front of them, not knowing that what lay ahead was much worse. As Patrizia C. McBride explained, the main weapon of Dada art with critical intent, photomontage, took on a different sensibility in Berlin:

While in a German context the initial inspiration for experimentation with visual and verbal collage may well have come from cubism’s “pasted-paper revolution,” it is significant that terms like Klebebilder and geklebte Bilder (pasted images) were soon supplanted by the generic term montage. To the radical artists associated with Dada and Constructivism, montage appeared preferable to the clumsy translations of the French collage because it directly evoked the world of machines, industrial production, and mass consumption, thus emphasizing the constructed quality of artifacts and their reliance on found materials and ready-made parts. The iconoclasm and antiestablishment streak of interwar montage practices have long been associated with an all-out assault on traditional notions of representation and narrative. In undermining the integrity of the artistic object, montage challenges the idealist premises that governed aesthetic dis- course in the nineteenth century, first and foremost the requirement that the artwork display a character of unity and organicity and thus allow for a hermeneuticc mode of reception based on the congruence between the whole and its component parts. Montage hinges on yanking elements out of their trusted environments and inserting them into new contexts.

In her article, “Weimar-Era Montage. Perception, Expression, Storytelling,” McBride stressed the formal impact of photomontage, but, when one is discussing Heartfield especially, it is equally important to establish the political context. The Weimar Republic was rent with competing factions that kept the government from effectively gaining control, and Heartfield was an unrelenting gadfly, stabbing at the heart of the new democratic Germany. During the 1920s, the Weimar Republic seemed a sinking ship run by fools and incompetents and their critical art was aimed towards the government and the favored and corrupt few who were prospering while the rest of the nation could not get out from under the animosity of the victors, especially France. In his book on The Weimar Republic, Stephen J. Lee explained the internal weakness within the government which prevented it from heading off fascism. The SPD was the most powerful of the coalition parties, but deliberately kept its interests narrow, directed to the working class, refusing to expand its appeal to the middle class. According to Lee, the Center Party (Zentrum or Z), mainly a Catholic party was uninterested in a Protestant constituency and would move to the hard right in the 1930s. The liberal parties, the DDP (Democratic party) and the DNVP (German Nationalist Party or the DVP), were “fundamentally divided between its progressive and conservative wings,” but were also not interested in the middle class. As Lee pointed out, “..after 1928, the DDP and DVP lost almost all their electoral support from the Nazis.”

Obviously, the government consisted of a variety of interests, none of which would seek support from the broad middle and build a support system for the Republic, leaving the vast unallied voters open for a hostile takeover. The fact that the Nazis moved into this vacuum of power was perhaps less a factor of political parties that pulled apart instead of pulling together and more about the nation’s lack of experience with self-governance. John Heartfield (once Helmut Hertzfeld) was a bitter opponent of the SPD and much of his work during the 1920s was directed against the Socialists. Like many adherents of the hard-left, he blamed the SPD for betraying the Left by lending a hand in crushing the Revolution in 1919. As a result of what seemed to be a failure of political nerve, Heartfield, along with most artists and intellectuals in the Republic were either sympathizers of or members of the German Communist Party. Lee explained the position of the party of Heartfield, the KPD (Kommunistisch Partei Deutschlands), in relation to the Weimar Republic:

The far left also had a role in the destruction of the Weimar Republic. In the crucial period after 1931, they refused to collaborate with the moderate parties to save the Republic; there was, in other words, no coalition of the left and center to hold back the advancing right. Why did this not happen?..the KPD had strong reasons for not doing this. In addition to their bitter memories of 1919, they had an ideological perception of the future which could not include the Weimar Republic. Stalin instructed the KPD not to collaborate in any way with the rest of the left, regarding the SPD as ‘social fascists,’ who gained ‘the trust of the masses through fraud and treachery.’ In the case of Thälmann, the leader of the KPD, saw Nazism as a catalyst for the eventual triumph of Communism. It would shake up bourgeois capitalism before collapsing in its turn–having cleared the way for a Communist revolution. According to this logic, it made no sense to help prolong the Republic..the KPD were therefore indirectly, but knowingly, involved in the rise of Hitler by 1933.

Heartfield claimed, incorrectly, that he joined the Communist party in 1918 during the founding congress but that congress did not take place until the end of December 1918 and the first of January in 1919. The assertion was one of emphasis–he was a strong and loyal member of the KPD from the start and identified so thoroughly with the working class that he wore overalls, styling himself as a Monteuranzug, an engineer or someone who assembles. As one of the first members of Berlin Dada, Heartfield and Grosz separated themselves and their art from the other members in their insistence that art had to be not only revolutionary as art but revolutionary as political art. The artists Raoul Haussmann and Richard Huelsenbeck and Hannah Höch, according to Dawn Ades in Dada and Surrealism, were more apolitical, focusing on an artistic revolution and steering clear of confrontation. Heartfield and Grosz, in contrast, put their art in the service of Communism and supported the working class and its struggles against the ruling powers.

Rudolf E. Kuenzli’s article, “John Heartfield and the Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung,” noted that “the new photojournalism of illustrated magazines with circulations of up to two million copies greatly determined the interpretation of social reality in Weimar Germany. Although the use of photo-essays was a powerful innovation, it served the interests of the middle and upper classes by never questioning the social and political structures of the Weimar Republic.” In other words, because photography had a claim on the “truth,” that is what the camera’s eye captured, the public would never question the authenticity of the photograph itself. However, this very public, even after decades of manipulation by the Second Reich, still did not understand that the photograph constructed a “reality” that could be completely disconnected from the truth. Coupled with explanatory text, the photo-essay was a powerful new discursive weapon.

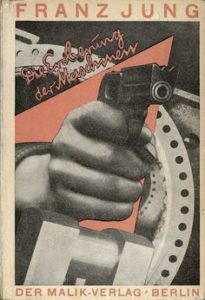

Heartfield and his younger brother, Wieland Hertzfelde (the “e” was added when he was an adult) set up a radical press Malik Verlag, which published left-wing literature. They published, for example, the German translations of the novels of American writer Upton Sinclair, another champion of the workers and of the truth from the perspective of socialism. With Heartfield designing the book covers, the press set new standards for artistic designs that not only caught the viewer’s eye but also sent out a political message, even to those who were just passing by a bookseller’s stall on a German street. Even more innovative these book covers were meant to be removed from the book so that the owner could see how the message–words and images–flowed beyond the front cover to the back cover.

John Heartfield. Der 9. Januar (1926)

Once opened flat, a complete picture or message was revealed on the dust jacket. The purpose of these publications, as Kuenzli noted, was to provide a counter-narrative to the mainstream flow of “information.” To that end, many of these covers had an apparently three-dimensional effect. The flat silhouette of George Grosz on the cover of Gesellschaft, Künstler und Kommunismus (1921) by Wieland Herzfelde was unusual. Heartfield turned the rather staid design of paper covers into an art form in their own right in which text played with picture and photography was sliced and diced and redeployed to jolt the passive reader.

In fact, the Weimar Republic was a golden age for book cover design. The back-to-front innovation was used by other artists and strong eye-catching or Blickfang work was not uncommon. However, the cover designs by Heartfield were, for the most part, far more complex and contained a great deal of information, as the artist wasted no opportunity to communicate. Although other designers also used photography, the use of the photograph, cut up and severed from its original context, was hostile and subversive to the status quo. By combining apparently “truthful” segments into a new assemblage (the artist as an engineer), Heartfield literally under-cut the meaning of the photograph by demonstrating just how easily and effectively the “truth” can be manipulated.

John Heartfield. Cover for Franz Jung’s Die Eroberung der Maschinen (1925)

After his early experiments with photomontage for Berlin Dada, Heartfield took his new political weapon, photomontage, and dedicated it to the promotion of the Communist Party and socialist ideals, an unwavering quest that divided his oeuvre during the Republic into two main bodies, one design oriented and the other politically directed. His book covers for Malik were works of layout and design, and although he also created montages for The Red Flag, a communist newspaper, his magazine covers for AIZ, also a communist publication, are more well-known. The next post will discuss Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung in relation to the mainstream photo essay and the work of pioneering editors such as Stefan Lorant and the power of illustrated news.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.