GERMAN ARTISTS AT WAR

The Good Soldier, Part Two

A battlefield is not an artist’s natural habitat. Fighting in combat is not an artist’s métier. But Franz Marc (1880-1916) wrote very militant and martial tracts for the Blue Rider Almanac. In 1912 he said stridently and forcefully:

In this time of the great struggle for a new art we fight like disorganized “savages” against an old, established power. The battle seems to be unequal, but spiritual matters are never decided by numbers, only by the power of ideas. The dreaded weapons of the `savages” are their new ideas. New ideas kill better than steel and destroy what was thought to be indestructible. Who are these “savages” in Germany? For the most part they are both well known and widely disparaged: the Brücke in Dresden, the Neue Sezession in Berlin, and the Neue Vereinigung in Munich.

His short essay was bristling with militaristic language and his images were borrowed from the barricades. Marc imagined the young artists with new ideas as “savages,” attacking the hills of old ideas guarded by the older generations, presumably the Munich Secession. The language of the Blue Rider artist, the images he conveyed can be seen as part of a phenomenon, on view mostly in Germany, which could be called portents of a coming war. The most famous writing on the necessity of a cleansing war, of course, came from the Futurist leader and poet, Filippo Tomasso Marinetti, but the Italian desire for a modern war was different from the many paintings that emerged in Germany, picturing a total war, a cultural apocalypse that would leave a wasteland in its wake. The most famous of these visionary artists was Ludwig Meidner, but Franz Marc also seemed to be envisioning the future to come with his 1913 painting, The Unfortunate Land of Tyrol.

Franz Marc. The Unfortunate Land of Tyrol (1913)

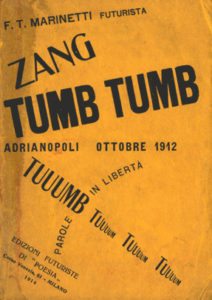

Unlike Meidner’s many end-of-the-world paintings, the painting by Marc referenced the war in the Balkans, a skirmish in an uneasy part of Europe that acted like a tinderbox, predicting conflagrations to come. The horses, Marc’s beloved animals, are black and in the middle ground, a red-hilled cemetery is studded with black crosses that will be sprouting across the Western Front in a year. During these pre-war years, with Europe seemingly edging closer and closer to plunging into war, artists veered between metaphorical images and literal responses to actual events. Marinetti also reacted the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913 with the poem, Zang Tumb Tumb, recounting in onomatopoeic words the sounds of the Siege of Adrianople during the first phase of these wars. While the Balkan conflicts were troubling, they predicted not so much a European war but were symptoms of the weakness of the Ottoman Empire which was losing pieces as territories were pulling away, seeking independence.

On the home front, in Germany, the nation was rattling sabers, imperial cavalry in full dress marched daily in Berlin, and the threat level seemed to be rising. In retrospect, Marc, like many artists, sensed the coming danger in his painting The Fate of Animals. But only in retrospect. In 1976, Frederick S. Levine investigated the origins of this work, dating it to May 1913, part of a larger group of animal paintings that the artist described as “utterly divergent pictures.” “They reveal nothing, but perhaps they will amuse you,” he wrote to his friend and fellow artist, August Macke. In addition to the reaction to the Balkans war on the Tyrol region, he was discussing The Tower of Blue Horses, The First Animals, The World Cow, and Wolves: Balkan War. The original title of The Fate of Animals was both extreme and poetic: The Trees Show Their Rings, The Animals Their Veins (Die Bäume zeigten ihre Ringe, die Tiere ihre Adern) and on the back of the canvas of a painting that Marc had declared would “reveal nothing,” he wrote, “And All Being is Flaming Suffering” (“Und alles Sein ist flammend Leid“). This complicated verbiage was distilled, on the advice of Paul Klee to Fate of the Animals (Tierschicksale), a more coherent title. The “fate” of animals in a burning forest is that of doom and death. They cannot outrun the flames that slash through the trees; the animals can only stand and wait or fruitlessly run for their lives. Certainly being caught in a blazing wood and being helpless would, in the near future, mirror the fate of the soldiers trapped in a war that would mow them down as ruthlessly as the flames would end the lives of the animals that stand in waiting for their “fate.” The painting was first shown in the Berlin gallery Der Sturm later that year, and its subsequent destiny or fate–of which more will be said later–was as eerie as that painting was as moving and prophetic.

Franz Marc. Fate of the Animals (May 1913)

The intense clashing diagonals and strong and fearless colors that envelop the stalwart beasts are painterly echoes of the writing of the artist penned a year earlier:

The first works of a new era are tremendously difficult to define. Who can see clearly what their aim is and what is to come; But just the fact that they do exist and appear in many places today, sometimes independently of each other, and that they possess inner truth, makes us certain that they are the first signs of the coming new epoch—they are the signal fires for the pathfinders. The hour is unique. Is it too daring to call attention to the small, unique signs of the time?

The question of the meanings of these “signs of the time,” was taken up by Milton A. Cohen in his article “Fatal Symbiosis: Modernism and the First World War.” He wrote,

As anticipations of the First World War, these images of war have been typically treated either as instances of artistic naivety (in glorifying a horror that artists could scarcely imagine) or as artistic prescience in sensing the blood that was already “in the air.” Yet such clichés miss the complexity of modernism’s relations to the First World War..Modernist artists had been at war long before they were mobilized in August 1914. Their primary enemies were the forces of artistic reaction: the hostile press, the conservative academies, the reactionary critics, the smug, self-satisfied bourgeoisie..By the early 1910s, however, as modernist innovation intensified, so did its struggle against reaction, and increasingly, modernists turned to war and violence for the vocabulary to depict it.

The author suggested that these paintings, like the language that accompanied them, were metaphorical and more directed to a desiccated art world than towards an imagined clash in the future. And yet, Marc depicted himself, riding a horse, in full dress uniform, in a 1913 painting that would prove to be a sad prediction of his own death.

Franz Marc. St. Julian the Hospitaler ( St. Julien l’Hospitalier ) (1913)

In another book Movement, Manifesto, Melee: The Modernist Group, 1910-1914, Cohen described the end of all of the bellicose images and manifestos once the War began in August of 1914. Instantaneously, artists flocked to war, acting as patriots for their nations, and ending the international sharing of artistic ideas that had characterized the two decades before the War. Faced with the enormity of actual war, normal artistic life ground to a halt and the militant words of Franz Marc would quickly seem naïve in the face of real battle. Cohen quoted French artist Albert Gleizes, who observed, “The present conflict throws into anarchy all the intellectual paths of the pre-war period, and the reasons are simple; the leaders are in the army and the generation of thirty-year-olds is sparse.” He ended sadly by stating a commonly held sentiment, “The past is finished.”

Franz Marc. Fighting Forms (1913)

To imagine Marc at war was to imagine an apparently gentle and spiritually inclined artist in alien territory, the battlefield. For years he had celebrated animals, considering them to be uncorrupted and closer to the spiritual in the world than humans, who were hopelessly compromised and unable to redeem themselves. The artist imagined nature itself as living and breathing according to hidden mystical laws that people, bent upon disturbing the forests and the fields, could no longer sense. He used color to bring symbolic meaning to his spiritual paintings, attempting to create a new language that would be redemptive for humans and at least bring a soothing balm to benighted beings.

Franz Marc. Animals in Landscape (Painting with Bulls II) (1914)

Marc’s language of colors echoed the ideas borrowed from Theosophy as put forward by his colleague Vassily Kandinsky in Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1911). Marc wrote that “Blue is the male principle, astringent and spiritual. Yellow is the female principle, gentle, gay and spiritual. Red is matter, brutal and heavy and always the colour to be opposed and overcome by the other two.” Writing in 2016, Eleni Gemtou noted that Marc projected human feelings of qualities, such as a lost spirituality, once the property of individuals, now found only in animals. In “Art and Science in Franz Marc’s Animal Iconography,” Gemtou discuss the empathy Marc felt for animals, imparting them with anthropomorphic qualities they probably did not possess. As the author explained,

Marc’s particular attitude towards animals must have been developed through many parameters and influences arrived at from both his own life experiences and the proceedings in contemporary science. He was familiar with animal iconography from his childhood up, as his father, Wilhelm Marc, was a professor at the Munich Academy specialized in animal and genre scenes. His approaches though were very different from those of his son, as he used to sentimentalize nature and anthropomorphize animal behavior in a more direct manner.

Despite this uplifting theme that drove his art, Marc, who came from a religious family, dreamed of a cleansing war that would bring about a new beginning. His last paintings of 1914 were marked by restless agitation on the part of animals who were instinctively sensing the dangers to come. In September 1914, the artist, filled with enthusiasm, volunteered and joined the calvary, a part of the military where he could ride a horse, but such units would soon become anachronistic. Romantic notions of a “cleansing” war quickly subsided in the face of reality. Marc’s close friend and fellow artist, August Macke died in October, very early in the war. Sadly, Macke’s wife, Lisbeth, had written, “And it’s wonderful to see how eager they all are to go.” Marc understood the magnitude of the loss of this man, his art and the future of his art. Correctly, Marc recognized the arbitrary nature of wartime death, writing of the “accident of the individual death which, with every fatal bullet, inexorably determines and alters the destiny of a race.” But he believed that this death would contribute to the greater good. “The blood sacrifice which turbrulent nature demands of nations in great wars they offer with tragic enthusiasm, without regret. The whole clasps loyal hands and bears the loss proudly under peals of victory.” Possibly through his own nationalism, Marc came to realize that any war ended globalism and watched the impulses towards a pan-European artistic network dissolve into an extreme nationalism. Instead of rising nobly and heroically to the great occasion, humans, faced with life of death circumstances, quickly descend to animal-like behavoir in order to survive. In his article, “A Murderous Carnival,” Richard Cork quoted Marc, writing in December of 1914, two months after the death of Macke, saying that “the most important lesson and irony of the Great War is certainly this: precisely the great triumph of our ‘technical warfare’ has forced us back into the most primitive age of the cavemen.”

Franz Marc. The Birds (1914)

In writing regularly to his wife and in asking her to make sure that the correspondence would be published, Franz Marc left posterity a remarkable record of a German soldier’s thinking and how his ideas evolved during the two years he served at the front. According to the analysis of Susanna Partsche in her book of his letters, Marc, the artist began with the belief that

Europe was sick and could only be purged through war. He spoke of an interntional blood sacrifice through which the world would be purified. He stricly rejected the view that economice interests had led to the War. He understood this War as a civil war, a “war against the inner, invisible enemy of the European spirit.On the other hand, he also believed that Germany would emerge strengthened from the War, and imagined a Europe under German hegemony. “Germanity will spill across every border after this war. If we want to stay healthy and strong and retain the fruits of our victory, we need..a life-force which penetrates all, without fear..of the unknown..which will bring us to our position of power in Europe..”

Like many artists, Marc tried to find the time to sketch the conflict, mostly in metaphorical rather than in documentary terms. For a brief shining moment, he was assigned to a camouflage unit where he painted “Kandinskys” on canvas, and he wrote of the new function of art in a modern war: “From now on, painting must make the picture that betrays our presence sufficiently blurred and distorted for the position to be unrecognizable. The division is going to provide us with a plane to experiment with some aerial photographs to see how it looks from the air. I’m very interested to see the effect of a Kandinsky from six thousand feet.”

But as the war dragged on, Marc became more and more disillusioned. In the beginning, the artist had believed that “There is something impressive and mystical about the artillery battles… I still do not think differently about the war. It simply seems to me feeble and lifeless to consider it vulgar and dumb. I dream of a new Europe, I … see in this war the healing, if also gruesome, path to our goals; it will purify Europe, and make it ready… Europe is doing the same things to her body France did to hers during the Revolution.” By 1916, he was yearning for an end to his service, and he wrote of the hopelessness of the War itself: “The world is richer by the bloodiest year of its many thousand year history. It is terrible to think of; and all for nothing, for a misunderstanding, for want of being able to make ourselves tolerably understood by our neighbors! And that in Europe!! We must unlearn, rethink absolutely everything in order to come to terms with the monstrous psychology of this deed and not only to hate, revile, deride and bewail it, but to understand its orgins and to form counterthoughts.”

In 1916, the Western Front was mired in the rain and in the endless Battle of Verdun and Franz Marc was but one of the thousands of men fated to meet senseless deaths during a campaign that lasted for months. After two years of being in constant danger, in 1916 he wrote, In this war, you can try it out on yourself- an opportunity life seldom offers one…nothing is more calming than the prospect of the peace of death…the one thing common to all. [it] leads us back into normal “being.” The space between birth and death is an exception, in which there is much to fear and suffer. The only true, constant, philosophical comfort is the awareness that this exceptional condition will pass and that “I-consciousness” which is always restless, always piquant, in all seriousness inaccessible, will again sink back into its wonderful peace before birth…whoever strives for purity and knowledge, to him death always comes as a savior. Marc was now thirty-six years old and, had war not come into his life; Marc would be at the peak of his creative powers, with a long and distinguished career ahead of him. But he was beginning to feel haunted and stalked by death. He wrote to his mother that “death avoided me, not I it; but that is long past. Today I greet it very sadly and bitterly, not out of fear and anxiety about it–nothing is more soothing than the prospect of the stillness of death–but because I have half-finished work to be done that, when completed, will convey the entirety of my feeling. The whole purpose of my life lies hidden in my unpainted pictures.” In 2013, Mark Dober, in his article, “Franz Marc: utopian hopes for art and the Great War,” of the great irony of the artist’s death. On March 2, 1916, Marc wrote to his wife Maria, “For days I have seen nothing but the most awful scenes that the human mind can imagine … Stay calm and don’t worry: I will come back to you – the war will end this year. I must stop; the transport of the wounded, which will take this letter along, is leaving. Stay well and calm as I do.” Then two days later he wrote what would be his final letter to her, saying, “Don’t worry, I will come through, and I’m also fine as far as my health goes. I feel well and watch myself.” According to Dober, Marc was dead two hours later.

Franz Marc. Broken Forms (1914)

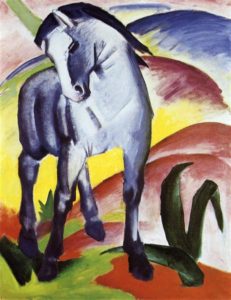

But the story is even more horrific than the final poignant letter. In the book, War, Violence, and the Modern Condition, Richard Cork quoted Marc’s commanding officer. The artist and his superior were on a reconnaissance mission, scouting territory during “a radiant early-spring afternoon..At the foot of the hill Marc mounted his horse, a tall chestnut bay, and as long-legged as himself..” The peaceful afternoon was violently interrupted by an exploding shell which burst open, spewing shrapnel. The shards hit the artist in the head so violently that he was nearly decapitated, instantly killing him. It is comforting to think of Franz Marc, living the last moments of his life in the radiant light, riding a horse that we hope was blue.

Franz Marc. Blue Horse I (1911)

In an odd postscript to the painting, Fate of the Animals was in storage at the storage unit for the Der Sturm Gallery, awaiting transport to a memorial exhibition in November. According to Levine’s The Iconography of Franz Marc’s Fate of the Animals, the storage area caught fire and the painting “..subtitled And All Being is Flaming Suffering, was itself consumed by fire. The immense task of restoration was immediately undertaken by Paul Klee who, with the help of Marc’s widow and the artist’s preliminary sketches, was able to reconstruct the structure of the original work..although the original structure remains intact, much of the continuity and much for the dynamism of Marc’s color scheme is gone from what..is one of the most vital sections of the entire work.” The restored ill-fated painting was purchased in a few years later for theMoritzburg Museum in Halle, but in 1936, Fate of the Animals was declared “degenerate art” by the Nazis, whereupon it vanished until 1939. As Levine explained, the painting was found and sent to the infamous Galerie Fischer in Lucerne, a money laundering operation performed by the Swiss for the benefit of the Nazis. The Fate of the Animals finally came to rest when it was purchased by the Basel Kunstmuseum.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.