AFTER THE GREAT WAR

Otto Dix and the Broken Soldiers

To understand the Treaty of Versailles, everyone should read Magaret MacMillian’s Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World. If reading a very long book on a treaty written one hundred years ago does not sound tempting, Paris 1919 is not so much about a century old past but about the future and the present. In 2007, MacMillian laid out a road map that explained how we got from there to here. A few years earlier, in 2000, historian David Fromkin published, A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East, which focused on the impact of the Treaty of Versailles and how the new world order came into being, and, for better or worse, created the Middle East we are grappling with to this day. In actions reminiscent of the “Scramble for Africa” in the previous century, France and England proceeded to carve the former Ottoman Empire like a great prostrate turkey between them like the practiced empire builder these nations were. The victors also began to slice off pieces of Germany, while hardly as large as the Middle East, was at least the size of a game bird, tracked down and brought to the kitchen table for dismemberment.

With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that the way in which the Paris Peace Conference mistreated Germany led to the Second World War. The victors, France and England, were in no mood for reason much less mercy; they sought revenge and vengeance. After all, Germany had started the War and after the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, victorious Prussia occupied France and forced it to pay reparations. The same fate was the least Germany deserved. The Great War was fought upon a deliberate German policy of bleeding the enemies–France and England–white, never realizing that that very strategy would also unleash a flow of casualties from its own body, which bleed its way to defeat. As MacMillian pointed out early in her book:

Millions of combatants— for the time of massive killing of civilians had not yet come— died in those four years: 1,800,000 Germans, 1,700,000 Russians, 1,384,000 French, 1,290,000 from Austria-Hungary, 743,000 British (and another 192,000 from the empire) and so on down the list to tiny Montenegro, with 3,000 men. Children lost fathers, wives husbands, young women the chance of marriage. And Europe lost those who might have been its scientists, its poets and its leaders, and the children who might have been born to them. But the tally of deaths does not include those who were left with one leg, one arm or one eye, or those whose lungs had been scarred by poison gas or whose nerves never recovered.

For the combatant nations, “recovery” meant that a generation needed to be replaced. For France and England, the loss of those expected to inherit and built upon the foundations of their parents was a devastating trauma. Revenge was not just about the past but about the lost future as well and in 1940 France preferred surrender to a new Germany rather than re-fight the Great War. But in 1919, France was eager to force Germany to pay reparations—132 billion gold marks–that would cripple the fledgling nation and to recover its “lost” territories of Alsace-Lorraine, the site of significant iron ore deposits. Other sections of Germany went to Poland. It should be noted that one nation was absent during this long Conference, Germany, which was confronted in May by the Treaty only when it was written. The nation reacted with shock over the so-called “War Guilt Clause” or clause 231: “The Allied and Associated Governments affirm and Germany accepts the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies.” The next clause, 232, demanded reparations which the Allies recognized in writing that the Germans did not have the resources to pay. These two sections alone, coupled with the Treaty’s insistence that Germany have only a small army and no air force, set the stage for the next war.

There are few heroes in this tangled tale, but the President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, might have had the best political instincts about how to conclude the Great War. Another prescient participant, the economist John Maynard Keynes, clearly foresaw the economic consequences. In his 2015 book, Britain, France and Germany and the Treaty of Versailles: The Failure of Long-Term Peace, Nick Shepley quoted Keynes, writing in 1920: “The Treaty includes no provision for the economic rehabilitation of Europe–nothing to make the defeated Central Powers into good neighbours, nothing to stabilize the new States of Europe, nothing to reclaim Russia..It is an extraordinary fact that the fundamental economic problem of a Europe starving and disintegrating before their eyes, was the one question in which it was impossible to arouse the interest of the Four. Reparation was their main excursion into the economic field, and they settled it from every point of view except that of economic future of the States whose destiny they were handling.”

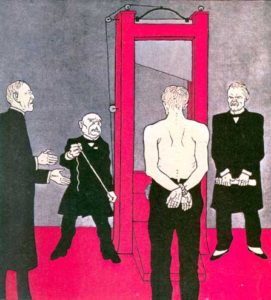

Simplissimus (June 3, 1919) This German cartoon was published a few weeks before the Treaty was signed.

We understand today that Woodrow Wilson, a Southern President, was a racist who resisted what was the first demand of the newly organized NAACP–block the release of The Birth of a Nation. Instead, Wilson, along with his friend, the director, D. W. Griffith, screened the film in the White House and endorsed the inflammatory movie. Once shown in theaters, The Birth of a Nation led to a revival of the Klu Klux Klan and allowed racism, never far below the surface, to rise up and bubble over. But, that said, Wilson, a former President of Princeton, was an intellectual visionary who arrived, as the leader of one of the victorious nations, in Paris with a dream of “self-determination.” There were vast territories unleashed when the Ottoman Empire and the Austro-Hungarian and the German Empires all fell, and Wilson commendably felt that these fledgling “nations” should have the right to determine their own destinies. However, he faced his allies which would have none of his idealism, took what they wanted, and left the remaining territories to their own devices. But Wilson did little to check the mood of vengeance towards Germany and said, a few weeks before the Treaty was signed, “I have always detested Germany. I have never gone there. But I have read many German books on law. They are so far from our views that they have inspired in me a feeling of aversion.” The League of Nations could be said to be Wilson’s consolation prize, but the American also rejected his hopes for a more peaceful future. The United States had never wanted to become entangled in the dark affairs of Europe and pulled back into isolation, leaving Germany to its fate, betraying Wilson’s Fourteen Principles, his proposal for a lasting peace. The world’s largest creditor nation had exited the global stage.

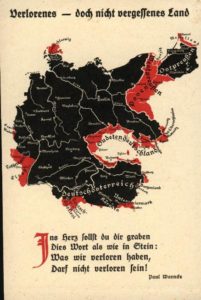

The postcard shows the territories pared away from Germany and Austria by the Treaty. The title of the card reads, “Lost but not forgotten land,” and the poem vows, “What we have lost/Will be regained!

The humiliation of Germany by the Allies was complete down to forcing the German delegation to sign the Treaty in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, paralleling the same shame inflicted upon France by the Germans in 1871. To the French people, which had been invaded, its lands wasted when they became the Western Front, these acts of vengeance were they least they could do to their ancient and prone enemy. To the German people, who had been lied to for four years, the surprise at losing the War was as great as the shock of being blamed for the War. They rejected Clause 231, which had established Germany as the aggressor and allowed the allies to demand land and reparations in return. There were reasons for the Germans to be surprised at their loss, for they had never been invaded. But it was the French command that decided that to invade Germany, as the American general John Pershing suggested, would result in needless loss of further French lives. After all, for all intents and purposes, Germany was soundly defeated, and a solution Wilson called “peace without victory” was more sensible. But from the German perspective, what tipped the scales towards surrender were mutinies in the military and political unrest at home. With the nation spiraling out of control and hurtling towards a Russian type revolution, the next move to conserve Germany was to end the war. The inexplicable surrender was never accepted by the German people, who were forced to accept this unexpected defeat and found themselves struggling to rebuild a nation deliberately disarmed and intentionally humiliated.

The Kaiser abdicated and fled to Holland where he would live long enough to see the rise of Hilter and another World War. A socialist Republic, teetering on warring factions that attempted to be a government, was founded with hopes of a democratic Germany. Psychologically wounded and financially destroyed, this new version of Germany made its way into the modern world. Given the unpromising beginnings of the post-War Republic, the Weimar years were marked by a blossoming of the arts in a nation that was in a constant state of turmoil until the Nazi party seized power and snuffed out the renaissance of creativity out of the ashes. Dada was an important Berlin expression of the collective anger and disgust of the intelligentsia with the German plunge into a destructive war, but, as a viable movement, Dada could not exist for long. Therefore, for the purposes of this series on post-War Germany, it is convenient to divide the post-War art into two parts: the immediate response to the aftermath of the War, Dada, and the art of the very soldiers who had witnessed its horrors; and then, some years later, the art that emerged, called “New Objectivity” or the artistic reaction to the culture of the Weimar Republic.

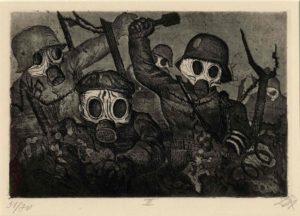

Stormtroopers during a gas attack, from Der Krieg (1924)

In his book, German Post-Expressionism: The Art of the Great Disorder 1918-1924, Dennis Crockett made something of the same case. There is a short period, coinciding with Dada, in which artists were using the pre-war style of Expressionism. Those Expressionists artists who returned from the War regrouped and, as with Cubism in France, Expressionism went from being a radical challenge to the establishment to a historical and accepted artistic style. Leading artists, Oskar Kokoschka, Otto Mueller, and others, became teachers in German academies and museums began collecting Expressionist works and filmmaker began incorporating the mood and feelings of the artists into their sets and stories. As Crockett noted,

Expressionism seemed to have become fashionable..The debate regarding the vitality of Expressionism reached its peak with the largest Expressionist exhibition to date during the summer of 1920. German Expressionism Darmstadt, arranged by the Darmstadt Secession, included 673 works by artists from all over Germany. In his lecture at the opening of the exhibition, president of the Secession, Kasimir Edschmid..condemned the superficial and commercial aspects of Expressionism: “What once seemed a daring gesture has today become ordinary. The advance of the day before yesterday became the mannerism of yesterday and the yawn of today..In a lecture delivered in Munich in October 1920, Wilhelm Worringer, one of the most distinguished Expressionist theorists before the war, added his voice to the eulogizing of Expressionism. He too criticized the many pseudo-Expressionists, “who know nothing about art.” But he observed a crisis of greater historical importance. According to Worringer, art had lost any sociological function it may have had before the modern era..Expressionism’s loss of vitality, its disintegration into “peaceful wall decorations,” represented for Worringer not only the death of Expressionist art, but the death of art itself.”

The question at the end of a war and the beginning of a peace was one of an appropriate language for the arts. On one hand, Expressionism was understood, quite rightly, to be part of a time that had come and gone. But on the other hand, Expressionism was, perhaps, for a brief time, the best style to explain the war and its consequences.

The constant bombing turned the landscape into lunar craters, from Der Krieg (1924)

One of those soldiers who returned haunted by what he had experienced was Otto Dix (1891-1969) and the series of prints he made of life in the trenches needed the excess that was such an important element of pre-war Expressionism. His memories of his time as a machine gunner during the four years of the war were turned into a Goya-esque sequence of fifty prints, titled The War (Der Krieg). This series is graphic and horrific, without color, drained of life, printed out in the black and white of engrained memory and dark dreams. Dix was an unimpeachable source and entitled to show to the German public that which the authorities were attempting to deny: he had been wounded five times and was awarded the Iron Cross in 1915. His was a voice that could neither be silenced nor denied.

Germany both invented gas warfare and launched the first attacks in 1916, but soon their soldiers also became victims, from Der Krieg (1924)

In writing A War of Images: Otto Dix and the Myth of the War Experience, Ann Murray wrote of how Dix defied the nationalistic ideals for the Germanic male, images that began to emerge as part of a propaganda effort to deny the outcome of the war. As she wrote,

Dix challenged the popular, romanticizing imagery of the heroic, militarized male, his pictures tracking attempts to nullify the mythologizing of the war experience that pervaded popular media..In 1924, Dix exhibited his cycle of etchings, The War, for the first time in Berlin. Based largely on the artist’s numerous wartime drawings..as a unit they form a pictorial record of the daily trials of the frontline soldier, recording the close contact and intimate knowledge of the subject that only one who had experienced war could hope to achieve. The catalogue produced for the launch of the series contained a foreword written by French pacifist writer and fellow veteran, Henri Barbusse, with whose novel, Under Fire (1916), Dix associated his etchings. The historical moment, the tenth anniversary of the outbreak of World War I, the so-called ‘anti-war’ year, when furious debates between Left and Right on social and political issues directly related to the consequences of the war reached a peak, was crucial to the exhibition’s message.

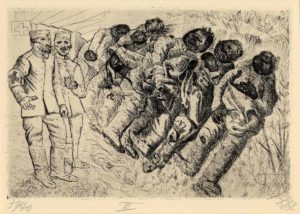

Corpses could not be buried and the dead and the living co-existed in the trenches, from Der Krieg (1924)

Given that Dix was a patriot who volunteered and fought bravely for four years, his series was not necessarily anti-war but it was definitely pro-reality when it came to the actual conditions of the War. As he explained in 1963, “I had to experience how someone beside me suddenly falls over and is dead and the bullet has hit him squarely. I had to experience that quite directly. I wanted it. I’m therefore not a pacifist at all – or am I? Perhaps I was an inquisitive person. I had to see all that myself. I’m such a realist, you know, that I have to see everything with my own eyes in order to confirm that it’s like that. I have to experience all the ghastly, bottomless depths of life for myself.”

An all too common sight made into a still life, from Der Krieg (1924)

War was a testimony of an eye witness, and the viewer should understand each image as the truth, based on sketches the artist had executed in the trenches. As shall be seen in the next post, Dix, a veteran, was disturbed by the way in which the wounded and maimed soldiers were treated in post-war Germany, where they lived, not as heroes, but as pathetic reminders of defeat. The public wanted to look the other way, and it was Dix who made them remember and, perhaps, feel some pity and responsibility. Even though Dix faced an audience increasingly reluctant to recognize the costs of the war and the sufferings of those who had fought, a decade later, these prints were still potent. It had been one hundred years since Goya’s Disasters of War, but in the time of Hitler, Dix’s War was confiscated and not viewed by the public again until 1983.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.