PHOTOGRAPHING WATER AND SKY

Jean-Baptiste-Gustave Le Gray (1820-1884)

Whether he wanted to be or not, Gustave Le Gray was a child of his time, deeply engaged in creating a national heritage for France through his photographic practice. After the French Revolution, the nation needed to redefine itself, and in order to understand what it would be, the nation of France turned back to its own past to learn what it was. The construction of nationhood was not a project of the state alone–France had too many successive governments during the nineteenth century for any one government to launch a program–the rebuilding of a new self-image was the work of generations of writers, artists, politicians, scientists, and workers. However, the governments of France all shared the same task: to turn France into a unified nation, knitted together under a single language and set of traditions and aspirations.

It would be wrong to assume that by the nineteenth century that France was a modern “nation” in the same sense that England and America were modern nations. Instead France had been a nation under an absolutist monarchy and the goal was to rule territory rather than unite the various units politically and culturally. The French language was spoken all over the world but not over the entirety of France. The only language heard universally was Latin in the Catholic churches. Over most of the territory, a local patois was spoken and one of the first efforts of the post-Revolutionary regimes was to enforce the French language, the language of the Revolution, the language of Paris. Because there was no national educational system until the nineteenth century and due to local indifference or hostility to outside interference, this effort to make the French be French would take one hundred years.

As Adrian Hastings noted in his book The Construction of Nationhood: Ethnicity, Religion and Nationalism (1997), “As late as 1864 a government report on the État de l’instruction primarie would admit that throughout the south of France, ‘Despite all efforts the French language spreads itself only with difficulty.'” and Hastings quoted another French historian as saying “French is for us a language imposed by right of conquest.” The relative backwardness of France compared to England and the lack of unified national identity suggests the significance of a return to a past and the importance of history to constructing nationhood. The interest in the historical past was certainly part of the Romanticism, which was an international social expression of individualism, but, in France, a concern with history was tinged with nostalgia for a past where there was order and certainty under a monarchy blessed by God. It is in the context that the work of Gustave Le Gray can be understood.

In 1851 Frederick Scott Archer (1813-1857), who had been working with photography in England since 1847 invented a new photographic process based on the use of collodion. Iodized collodion was poured over a glass plate and when the plate dried a film was formed. The plate was usually exposed while still wet in the early years, producing a strong negative that could produce multiple positives. Archer announced his discovery in 1851 and, of course, William Henry Fox Talbot did what he always did—he claimed infringement on his patent for the Calotype. Sentiment against Talbot’s possessive attacks on photographers was rising and after vigorously defending himself, Archer, a mild man, wrote another article on the collodion process in 1854. Like Daguerre, he gave away his knowledge and his chemical formula, opening the door to mass media through the reproduction of photographs. The result of Archer’s efforts was that the new photographic process, vastly superior to the Calotype and the Daguerreotype, took over from the Daguerreotype and both older forms of photography were left by the wayside. Sadly, the inventor of the collodion process, Archer, died a few years later in obscurity.

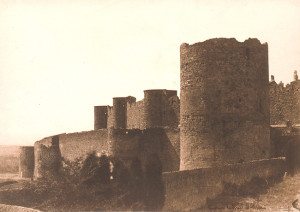

The collodion process allowed Le Gray to solve a a problem that could not be solved with existing technology–the blank sky. Due to the long exposure times necessary to take a photograph, the brightness of the sky would, during exposure, simply bleach out, leaving a blank space without the definition of clouds. The sky could be photographed by itself; the ground and its objects could also be photographed in their own right; but the two could not be photographed together with equality. Given that photography was indebted to painting for notions of appropriate subject matter and composition and framing, the undifferentiated expanse of white sky was an issue to these artistic photographers. An image from the Mission Héliographique, The Ramparts of Carcassone (1851) shows that Le Gray had a very interesting solution which actually utilized the sky as a dramatic backdrop for the striking silhouette of the ancient fortress.

Although there are existing exceptions, Édouard Baldus generally preferred a closer cropping, eliminating most of the sky which, for documentary photography, was a low information area. Clearly Le Gray was interested in the possibilities of the sky but was thwarted by the effects of the light itself. The background for the fortress takes up nearly half of the image, holding its own compositionally, as if making a promise. While photographing landscape was relatively unproblematic, photographing the sea was as difficult as photographing the sky. With the limitations of the emulsion of the day, the sea or water would often print out very dark and any movement of water, such as waterfalls or waves, would translate into a white smear.

Once Archer released the formula for the collodion process, Le Gary could approach the land-sky-sea problem from a different angle. With the film created by collodion, the negatives were now easier to work with. Unlike paper which was relatively thick, the film could be easily cut with some precision. It is difficult to appreciate how innovate it was for Le Gray to manipulate photography by using different negatives in combination to produce a positive that showed both sky and sea and land in one seamless picture.

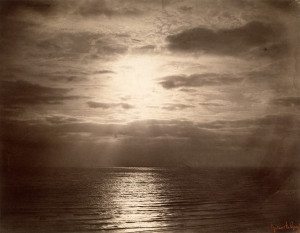

Gustave Le Gray. Solar Effects

There seem to be no extent statements by Le Gray on how he was inspired to use the revolutionary method of combination printing with multiple negatives, nor are there any instructions from him as to how he printed out the final image. It is possible that, aware of the competition among art photographers, he was prudently silent. Whatever his procedures, Le Gray’s seascapes, which combined separate shots of sky and sea in one stunning image, were considered a major if not astonishing development in his own time. The photograph of Solar Effects suggests that two photographs were taken at different times, one favoring the sea and one adjusted for the sky, put together along the horizon line into one new negative and printed as a positive.

With a new concept in mind, Le Gray gathered together skies and seas from the various French coasts. Although he apparently combined a Normandy sky with a Mediterranean sea or vice versa and although the cutting and pasting of negatives seems to have been known at the time, the technical tour de force overcame any qualms over authenticity. The Getty Museum quoted one contemporary critic as musing, “It is a difficult matter to condemn as utterly untrue pictures to which universal praise is given for truthfulness; but still the laws of nature, as interpreted by science, are unerring.”

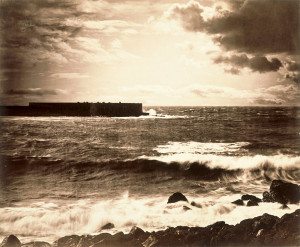

Some of Le Gray’s cloud studies, resembling those of Eugène Delacroix and John Constable, have survived and an expert can track the appearance and reappearance of a particular sky from one seascape to another. Among his most remarkable images is that of breaking waves, a very difficult motion—to freeze water—in a time when motion could not be stopped. Sète is on the Mediterranean coast and is often called “the Venice of Languedoc,” because it is the starting point of the Canal du Midi. An old port established under Louis XIV, Sète is, after Marsailles, the largest port in France, but it is interesting that Le Gray chose this site for his “great wave.” Guarded by the great fortress of Carcassone, this is “Cathar Country,” the Languedoc region where the language of Oc was spoken. The Cathars were a religious and regional group, which for centuries resisted the orthodox Church and the attempts of a central French authority to rule them. Their so-called “heretical” uprising against the Church and State was brutal on both sides and finally put down by the mid thirteenth century, ending in a mass immolation of the dissident Cathars of Languedoc. Although today, Sète is a favorite tourist destination, during Le Gray’s time, this was one of the territories historically resistant to nationhood, and today the native still refer proudly to their local ethnic heritage. For Le Gray, a native Parisian, to photographically “claim” Languedoc as part of the history of France was a powerfully nationalistic statement.

The Great Wave, Sète (1856–59)

In 1857-9 the artist brought out an album of seascapes called Vistas del Mar, called by Marc-Antoine Gaudin, a critic for the journal La Lumière,“the event of the year.” One of the surprising aspects of early photography on paper was how large the prints could be. Le Gray used a large plate of glass, measuring about 12 x 16 inches, a very generous size for a photograph even today. This ambitiousness suggests a Salon mentality on the part of Le Gray–the more imposing the image the more the public would be impressed, and the size alone would elevate the photograph to the level of art. It was at this time, apparently at the height of his fame, that Le Gray decided to go into business. In 1855, Le Gray opened his own studio on the Boulevard du Capucines and from contemporary accounts, it seems that he overspent from the very beginning. The Metropolitan Museum of Art quoted L’illustration, which in 1856 was marveling at the elegant quarters:

From the center of the foyer, whose walls are lined with Cordoba leather..rises a double staircase with spiral balusters, draped with red velvet and fringe, leading to the glassed-in studio and a chemistry laboratory. In the salon, lighted by a large bay window overlooking the boulevard, is a carved oak armoire in the Louis XIII style..Opposite over the mantelpiece, is a Louis-XIV-style mirror..(and) various ptgs arranged on the rich crimson velvet hanging that serves as backdrop..Lastly on a Venetian table of richly carved and gilded wood, in mingled confusion with Flemish plates of embossed copper and Chinese vases, are highly successful test proofs of the eminent personages who have passed before M. Le Gray’s lens..However, the principal merit of the establishment is the incomparable skill of the artist..

This account reads like a recipe for financial troubles, but there was no reason why the photographer should have not been successful: he was close to the Imperial family, having photographed the Empress, the newborn heir apparent to the throne and the French army itself. But Le Gray disappointed his backers and his creditors and his business venture failed. Apparently Le Gray had been a spoiled child and was happy to take from his backers without managing to turn a profit, despite doing the best work of his career. The contemporary French photographer Nadar seems to have correctly diagnosed Le Gray’s difficulties–he had no head for business. The collodion process made mass media possible and commercial photograph, especially portraiture, became extremely profitable. Le Gray’s clientele was always a small and elite one. There were simply too few patrons for his work, and Le Gray was forced to flee the country and his creditors, using the unlikely escape route of the yacht of the famous author Alexander Dumas (1802-1870).

Dumas was interested in visiting Italy during its struggles to become unified and, out of his admiration for Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882), the leader for nationhood, took Le Gray and the rest of his entourage to the battle lines. Although at first Le Gray produced some interesting work as a photojournalist, a mysterious falling out between Dumas and some of the members of his entourage, including Le Gray. The photographer, along with two other stunned passengers were abandoned on the island of Malta by the mercurial and imperious writer. For Le Gray it was the end of his career as a photographer. Having abandoned his wife and children, Le Gray was able to make his way to Egypt where he supported himself as a teacher and artist until his death in obscurity, remembered by a few good friends such as Nadar.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.