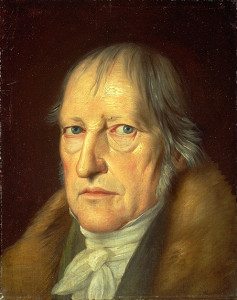

GEORG WILHELM FRIEDRICH HEGEL (1770-1831)

Hegel and his Impact on Art and Aesthetics

Like any aesthetician, G. W. F. Hegel does not get involved in any particular movement or style or work of art, but, that said, he was very definite about the kind of art where Beauty could be found. Like Emmanuel Kant, Hegel brings art and freedom together and anticipates the idea of art-for-art’s sake. For Hegel, the Idea is always opposed to Nature. The mind is contrasted to the mindlessness of matter or nature. The mind creates art, which gives an idea to nature. This idea is the unity of the externality or objectivity of nature and the subjectivity or personal vision of the artist. As with Kant, the spectator of the work of art is as important as the art maker for Hegel. Beauty in art is the emanation of the Absolute or Truth through an object. Beauty can be shown only in a sensuous form called the Ideal, which transcends the Idea to become a special form. Like all of Hegel’s triads, nothing is lost: nature and idea are the Other to one another but together they create an organism, the work of art.

The contemplative mind strives to see the Absolute. In order to see Beauty, this detached mind must transcend nature. By freeing itself, the mind perceives the spiritual content of the work of art, which must also be free in order to be Beautiful. Kant insisted that the higher form of beauty had to be free and independent and Hegel followed suit.Hegel insisted that, to manifest Beauty, art must expel all that is external or contiguous or unnecessary. Remember, in Hegel’s system, each part of the triad must be “pure” and can contain only its dialectical opposite. For art to reveal Beauty is to reveal Truth, which can only be pure. This is why art can never imitate nature, which is, mindless and irrational. Nature must be reversed with its antithesis, the idea, which brings about the inner unity necessary for spiritual content: nature, idea, spirit = art. If art must be free, then art should show, not just Beauty and Truth, but Freedom itself, which is the property of the free mind. Hegel, true to his age, is a child of Neoclassicism and, like many Germans, was looking back to a Golden Age when human beings were free. Part of being “modern” is being un-free. Society has demands, which are placed upon people who have lost their sense of wholeness and self-actualization. Thinking along the same lines as Friedrich Schiller’s “alienation,” Hegel felt that his own age was a diminished one. Therefore, the artist should take subject matter from the past, a heroic age populated by characters that were free of the social restrictions so prevalent of the industrial age.

Ancient peoples, Hegel assumed could determine their own destinies and could make their own lives on their own terms. While the current times were particular to the modern period, the primeval era could manifest life in its universal and essential form. By stripping the process of living down to its basics, one is nearing the first cause of life, the logic of existence in which one is in the process of becoming. One can “become” only if one is free, linking the rational with the free to the universal. Hegel explained art’s predilection for the depiction of the high-born because those individuals are free, assuming that the lower classes are unsuited to being represented because, being subservient to their masters, they can never be free and therefore, never universal. Stripping away the elitist assumptions that princes are preferential to peasants as subject matter in art, it is possible to note that Hegel was insisting that the artist attempt to reach the universal through art. But Hegel was a also creature of history. The idea of “princes” should not be taken so literally in the modern era, an era badly suited to the classical art of the past. Hegel understood that the antique forms were indissolubly linked to their own time. Greek and Roman sculpture expressed the ideal in universal poses of repose, rather than with active poses linked to a particular action. But in the modern age, the new society did not lend itself to rest and repose, which could be found only in the spirit of the artist or in his personality. The modern age has come to realize that any hope of freedom or infinity is impossible and the human mind has no escape, except into itself. The new subjectivity of the spirit produces a new kind of art in which the artist imprints him or herself upon the art. the result is Romantic art which is the art of modern Europe. Unlike ancient art which needs the sensuous manifestation of the classical statue, Romantic art gives rise to an independent spirituality or mind which leaves behind its traces as sensuous remnants. It then logically follows that sculpture is not the appropriate receptacle for the spirit of the Romantic artist. Clearly, Hegel could not conceive of a form of sculpture that was allowed to transcend its traditional role of starting with and then transcending nature into idealism. Sculpture was, despite its attempt at perfection of form, too bound to the “real.”

Painting, in its two-dimensional flatness, is the most suitable manifestation for the spirit, mind, and personality of the artist. Painting is appearance, rather than actuality or matter and, as a mental process of the artist, is subjective. The external world is allowed to enter into the subjective world of art because concrete reality is transformed through art. Hegel allows for the ugly, the grotesque, suffering and evil in Romantic art as the other necessary element in his dialectic. Beauty must contain ugliness, just as Truth conceals Lie, and for reconciliation to take place beauty and ugliness must be reconciled into a concrete unity that is a higher form of Beauty, which is also Truth. Although Hegel’s ideas on art and aesthetics were inspiration for those who believed in “art-for-art’s-sake” or the avant-garde, his deterministic philosophy was politically very retrograde and repressive. There is another way to view Hegel’s “princes.” As with his colleague at the University of Berlin, Johann Gottleib Fichte, Hegel believed that Germany’s destiny was to become the dominant power in Europe, due to the forces of history, which had passed England and France and had progressed to Germany. A snob and a social climber, the consummate academic ego, Hegel was enamored of power and, during the French occupation of Germany, was thrilled by Napoléon. Like Fichte, he believed that Germany was a chosen nation and that it had the moral right to pursue its hegemonic dominance ruthlessly with “absolute privileges over all others. It should behave as the spirit willed it and will be dominant in the world…” With Hegel, war and dominance as historical tools of historical progress entered into European thought. Because his philosophy was based in history, Hegelian aesthetics also impacted upon art history and art criticism. The basic structure of art history has followed his model of successive and contrasting movements.

The history of art has been told as a succession of conflicting styles by Heinrich Wölfflin and as a tale of successive and contrasting movements by history based upon formalist models. The ancient produced the modern, the universal produced the particular, the timeless produced the contingent and modern art is the synthesis of these conflicting forces. As a synthesis, Romantic art must be independent and begins to exist on its own. Hegel’s aesthetics inspire the theory of the avant-garde: thesis, antithesis, synthesis—Neoclassicism, Romanticism, Realism, and so on. One avant-garde movement, assigned the positive position, opposed another avant-garde movement, the negative or counter position, resulted in a dialectic, which pushed art ever forward and towards an absolute of purity. The result of the influence of Hegel, art criticism, especially under the American art writer, Clement Greenberg, was model of artistic progression from representation towards abstraction. By using the avant-garde and its oppositional stance as the engine of change, art history in the Twentieth Century has been Hegelian in structure. However, Hegel’s rigid structures were as artificial as those of Kant. He may have thought of his method as being dynamic and his dialectics as showing history moving and changing, but the model itself was also architectonic. Just as Kant thought in terms of antinomies, Hegel through in terms of triads: thesis/antithesis/synthesis–to use modern terms, but these formations had distorting effects when applied to actual history itself. Indeed art history has inherited these distortions which in effect force out historical art movements that do not “fit” the model. An excellent example would be that of Heinrich Wölfflin’s Principles of Art History (also known as Fundamental Concepts of Art History), written one hundred years after Hegel’s lectures and published in 1915, during the Great War. It was finally translated in to English in 1932.

Wölfflin actually materialized Hegel in his lectures in Berlin where he projected dual images side by side, a compare and contrast technique of discussion he pioneered. His speciality was the comparison of Renaissance and Baroque art and his fame and influence rested upon his notion of pairs, or units of style. The Renaissance was preceded by an early or “primitive” archaic style which had no particular artistic form. But because art is never “finished” these early stages “developed” into a final or higher form, the High Renaissance, where all the forms come to fruition. In the schema of Wölfflin, the Renaissance which recaptured the perfection and the grandeur of the ancients, was followed by its opposite, the Baroque. This contrast was expressed by the art historian in terms of famous pairs, linearly and painterly, plane and recession, closed and open form, unity and multiplicity, absolute and relative clarity. However, embedded in these pairs (thesis/antithesis) are value judgments which plague art history to this day. The Baroque is considered a “falling off” or a lesser style, lacking the perfection of the Renaissance, and, in addition, Wölfflin removed the phase of Mannerism which is a transition between the Renaissance and the Baroque. Wölfflin tended to concentrate on Italy and pay less attention to local variations of the Baroque, such as Dutch art, for example, where the pairs might not work as well. Clement Greenberg’s famous essay of 1961, “Modernist Painting” (to be discussed at greater length in another post) is a prime example of an art critic assuming that art “progressed” from a low form to a high form or climax from which it must fall. Greenberg began with Manet as the thesis and began a linear progression with the Impressionists coming out of the master and the Post-Impressionists coming from their predecessors in turn. For Greenberg, inspired by Hegel, art was progressing, moving towards, striving towards a perfection in which it had to shed all elements that were impure, such as dimension and representation, until it (art) evolved into pure abstraction. From that high point of perfection, which might have been post painterly abstraction or hard edged painting, art suddenly fell into an alien and lesser form of low art, called Pop art. Greenberg was stymied by the appearance of Pop art and its vernacular origins. Hegel, as was noted, had, like Greenberg, a strict notion of what comprised “art” and it was high art or what the art critic termed “significant’ art. The problem is that what Hegel created was a theory of art and aesthetic that defined art, but what Wölfflin was writing was a history of art–something very different. The aesthetics developed by Hegel allowed him to elucidate a theory of art evolving over time but he never intended his philosophy to be thought of as history. Instead his work was an accounting for the artistic impulse, again something very different from the history of art. When his aesthetics are carried over into specific historical periods problems immediately arise but the thesis/antithesis formula was so very convenient that it became a framework through which art was taught.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.