HIPPOLYTE BAYARD (1801-1887)

Another Inventor, Another Process

The First Fake Photograph

Among the many oddities of the history of the invention of photography is that not only was photography invented by so many people at the same time, but also that few of these individuals made a career in photography itself. The fact that the attentions of Louis Jacque Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851) and William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) wandered from photography and towards other interests indicates that the invention of photography was something stumbled upon and not well understood as to its future purposes or applications either by its originators. In some ways Daguerre and Talbot were like the early developers of the computer, who had an amazing machine with little initial idea of what to do with it. It would be up to the next generation of photographers to turn it into a commercial enterprise that would sweep the world, moving with lightening speed from continent to continent, and then into an artistic endeavor. Although establishing photography as an art or a photograph as a work of art would take nearly a century, the last major inventor of photography, Hippolyte Bayard (1801-1887), was the first to truly explore the artistic possibilities of an image captured on paper. He was the only inventor to sustain a career as a photographer. Bayard was also, it should be noted, the first person to understand that a photograph did not always tell the truth, in demonstrating that a photograph could be a lie.

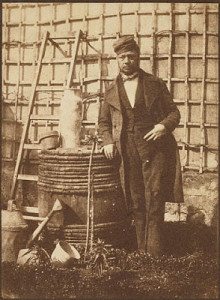

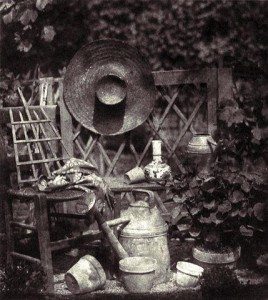

Hippolyte Bayard. Self-Portrait in the Garden (1847)

Although Bayard, a civil servant working in Paris, had been experimenting with photography for years, he was the dupe of political favoritism on the part of François Jean Dominique Agaro (1786-1843), who wanted to support Daguerre and sideline Bayard. Bayard’s experiments had led him to create a number of unique positive images on paper and, in fact, he had actually held a small exhibit of his work before Daguerre “announced” or gave his own process to the French public. By this time, the terms coined by John Herschel–“photography,” “positive,” “negative,” and so on, were well known and were becoming, as Herschel would have wished, universal. It is perhaps a small point, but a “photograph” is not a “Daguerrotype,” but the distinction made no difference for the fate of Bayard’s reputation. The cards were stacked against him. After Daguerre’s bombastic disclosure in January of 1839 the public’s interest focused on the silvered plates:

The discovery I am announcing to the public is of that small number which, in principle, results, and potential influences extraordinary inventions. It consists in the spontaneous reproduction of the images of nature received in the camera obscura–not with their colors, but with the great delicacy of tonal gradations..Daguerre went on to note that “With this process, without any notion of drawing, without any knowledge of chemistry, or physics, it will be possible to take, in a few minutes, the most detailed views of the most picturesque sites..The Daguerrotype is not an instrument to be used to draw nature, but a chemical and physical process which gives her the ability to reproduce herself.

This announcement in itself is interesting, because it stresses the passivity of the operator and, indeed, the ignorance of the photographer, who is merely in the service of nature. The stress on the active effects of science, as noted in Daguerre’s use of perspective in his dioramas, perhaps underlines his support and the reasons for his support in the scientific community, the intellectuals who were behind the push to place Daguerre in the forefront. His benefactors were distinguished members of the Académie des Sciences, François Arago, the famous physicist, astronomer, director of the Paris observatory, secretary to the Académie in perpetuity, a member of parliament, and Jean-Baptiste Boit, a physicist, and Alexander von Humboldt, the famous explorer. In addition, Daguerre immediately embarked on a scheme to pair the selling of how-to instruction manuals with the appropriate cameras made by his partner, Alphonse Giroux, which were ready to be purchased at the time of the official August announcement. Giroux would become the leading manufacturer of cameras fitted expressly for making Daguerrotypes. Against such a panoply of validators, special equipment, and commercial promotions, Bayard had no chance. Although it seems that Bayard’s method of capturing “nature” was a combination of that used by Daguerre and Talbot and he properly presented his findings to the Academy in February, no description of Bayard’s photographic work was ever published at the time.

Few of Bayard’s early photographs survived but it is know that at least thirty had been displayed at the 1839 Paris exhibition along with paintings, prints, sculptures, apparently under the category of “curiosities,” or, to put it another way, clearly placed in the category of art, not science. Like Talbot, Bayard made photograms, but produced his positives from a recipe of his own devising. His photographs of the windmills of Montmartre were taken on an ordinary sheet of writing paper–stationary. The paper was then dipped into two different baths of his silver solutions and placed in the sunlight. Then the sheet was covered with a uniform covering of black elemental silver, dipped into yet another bath and placed, still wet, into the back of the camera, which was pointed in the direction of the windmills. After an hour exposure, the blackened silver was etched away and bleached to various shades of gray. Then the paper was placed in a final stabilizing bath.

Unique Positive Print on Paper. Windmills of Montmartre (1839)

Seven months after Daguerre’s announcement (not the explanation of the Daguerreotype process), Bayard made another attempt to make himself known on Bastille Day of 1839. He showed a number of images at an exhibition for the benefit of earthquake victims in Martinique. With his displays, Bayard was the first photographer to show his work in public. These images were seen by François Wey who wrote,

They resembled nothing I had ever seen..One contemplates these direct positives as if through a fine curtain of myth. Very finished and accomplished, they unite the impression of reality with the fantasy of dreams: light grazes and shadow caresses them.

Bayard tried hard to bring attention to himself but neither the exhibition nor the good critical notices could stand in the way of the great weight and prestige of science leaning towards Daguerre. There seems to be a split in the mind of the government officials between art and science, and Bayard, as an artist, was probably put in second place. As a public employee confronting a powerful politician and a daunting array of scientists, Bayard naturally accepted a small sum of money for further research in return for allowing Daguerre to take the credit for an invention that was also his. Perhaps Bayard did not grasp the significance of his sacrifice until after the announcement which cause such excitement in August 1839. Humiliated by the snub, Bayard retaliated by posing as a victim of a “drowning” and wrote on the back of the fake death notice:

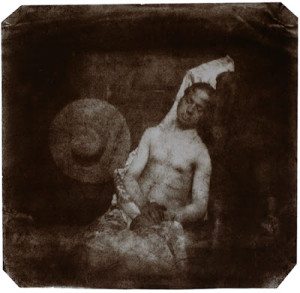

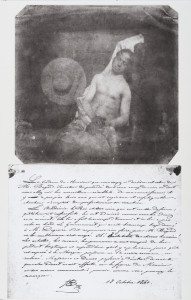

The corpse which you see here is that of M. Bayard, inventor of the process that has just been shown to you. As far as I know this indefatigable experimenter has been occupied for about three years with his discovery. The Government which has been only too generous to Monsieur Daguerre, has said it can do nothing for Monsieur Bayard, and the poor wretch has drowned himself. Oh the vagaries of human life….! … He has been at the morgue for several days, and no-one has recognized or claimed him. Ladies and gentlemen, you’d better pass along for fear of offending your sense of smell, for as you can observe, the face and hands of the gentleman are beginning to decay.

Portrait of the Artist as a Drowned Man (1840)

Jacques-Louis David’s

As part of a group of artists and actors, Bayard was unusually self-reflective and self-dramatizing in his work, producing works of interpretive self-portraits–himself in despair and himself as a rather well-to-do middle class male snug in his own garden yet well dressed in a respectable suit, himself as a man of leisure contentedly working with his gardening tools. He obviously had an understanding that the role of photography could be both the conveyor of truth and the inventor of fiction. The Drowned Man belonged to the tradition of theater or painting and resembled nude studies employed by academic artists and was clearly a work of fiction and narrative. Clearly this half-nude pose would have been one of the first, if not the first nude study in photography and it is in the tradition of Jacques-Louis David’s (1728-1825)

Despite the theatrics and the dramatics, what is interesting about Bayard is his subsequent career. His method had less usefulness to the public or to other artists, because the unique positive did not allow for reproduction nor did his use of paper offer the clarity and detail of the Daguerrotypes. But he seemed to have been dedicated to paper and by 1842, Bayard switched to Talbot’s superior method of positive-negative and became one of France’s leaders in the art of the Calotype. In the early 1840s, he studied his garden, not for its foliage but for its objects, sometimes placing himself in this setting, with posts and pitchers nicely grouped for compositional effects, turning a record of a place into a formal study of shapes and textures.

His studio work with his collection of forty sculptures showed a Talbot-like penchant for still life arrangements and Bayard even included himself in a very early positive print.

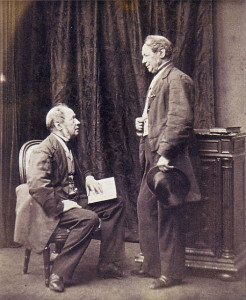

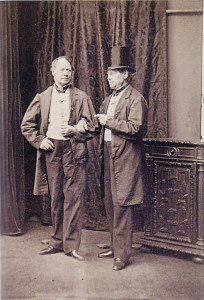

Bayard was indeed unusual in the insertion of himself as an actor in his own staged scenes. These images might have been a bit of a self-advertisement, for in 1857 Bayard set himself up as a professional photographer in Port Mahon. Late in his career, when he was still experimenting he indulged in some trickery and created a series of double self-portraits in 1860-61.

Daguerre was awarded honors from the King Louis-Philippe, made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor and was then further elevated to an “Officer” of the Legion itself. It was a good time to retire to the small town of Bry-sur-Marne at the age of fifty-two, living on a government pension. Advances and improvements in photography would be carried on by others like Bayard. After the struggle to claim his right as one of the inventors of photography, Bayard experimented with Daguerreotypes, documenting old chateaux in the Loire Valley. Although these images are extant, there may have been others commissioned by the government but, if so, no record of them exists. That said, the government clearly had its eye on Bayard and the numerous self-portraits and the quiet private garden studies, however, were not the future of Hippolyte Bayard–he would become a documentarian after all. In a way, his restrained silence on the occasion of Daguerre’s investiture was rewarded, and Bayard was among the photographers appointed in 1851 to the government’s project to record and photograph the ancient buildings of France, the famous Mission Héliographique.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.