Inevitable Design

Becoming Modern

Art and design define our lives for us, teach us how to function in the world, and, from time to time, produce an object, whether human or inanimate, that is so fulfilling that it become unnecessary to alter the blueprint. Since the 1920s, short skirts for women have been as timeless as the trebuchet or siege engine. We may make art but we are made by design. An apparently simple object such as a bow and arrow, took centuries to prefect as countless nameless designers searched for a shape that would be both efficient and effective. In response to the new weapon, the human body had to be trained to move reacting to the demands of bending the bow and the needs of the taut string that needed to be pulled away from the bow and stretched for the length of the archer’s arm. Thus the body in turn had to be redesigned: one arm had to be held out, stiff and still and unmoving, the hand gripping the bow. The other hand had to grip the thin string, strain its flexibility by drawing the twine towards the face of the archer who must also somehow balance an arrow on his bow hand and pull the shaft back with the string. And the length of the arrow and the length of the string must be perfectly calculated to the body of the archer. The bow and arrow was so necessary to human survival that most cultures around the world invented this hunting weapon and all cultures came to the same conclusions, creating a universally satisfying way of sending a shaft fast and hard through the air and into the body of an animal. But excellent design does not suddenly manifest itself. Design is a time based process and designers can take years or even generations to work their way towards a final design that would be truly satisfying and seemingly inevitable. We cannot calculate how many generations it took to perfect the bow and arrow but we can be sure that evolving knowledge was passed from maker to maker until the ages of experimentation, trial and error were over and the age of perfecting the weapon began.

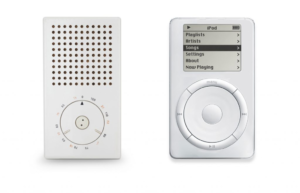

“Good design is as little design as possible,” said a young German designer. One of the most important designers of the late twentieth century, Dieter Rams (1932-), is best know for his distinctive signature Braun products. He also considered the “unspectacular” elements of design to be the most important. In other words, Rams was advocating a design stripped down, shorn of all non-essentials.If the design evolves towards this kind of satisfaction, it is a design that will last. “I always strive for things to be sustainable. By that I mean, the development of long-lasting products–products that don’t age prematurely, which won’t become out of style. Products that remain neutral, that you can live with longer,” he explained. In the 1960s, when he was quite young, Rams, a visionary, pushed design out of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century, making this important step forward by looking back several decades to the Bauhaus of the 1920s. What Rams took from the Bauhaus was the clean simple shapes, stripped down to the essence of their forms. His 1958 design for a transistor radio, a new invention, was a masterful understatement of basic geometry. But the Dieter Rams idea for the transistor radio design did not originate with him, the iconic design began in Texas via Holland.

The inventor of the transistor radio was Dr. Heinz De Koster who was born in Germany and educated in the Netherlands during the Second World War. Little is written of him other than the fact that he was the inventor of the transistor radio, in terms of technology. But the transistor itself was an invention of what Winston Churchill called the “Wizard War” and its technologies, such as radar which led to the invention of the transistor in 1947. The engineers at Bell Labs in New Jersey, John Bardeen, Walter Brattain and William Shockly were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1956. According to Cari Romm writing for the Smithsonian Magazine, reported that in 1951, “..two companies teamed up to begin researching a new idea: a small, portable radio. Texas Instruments supplied the transistors to Idea Inc., who designed, produced, and—three years later—finally debuted the Regency TR-1 in November 1954, just in time for the holiday-shopping season.” As can be seen, the first transistor radio was bright and glittering, its strong colors hiding its technology, holding its own modernity at bay. Small and portable, it allowed the new consumer group, the teenagers, to listen to their music, rock ‘n’ roll, in privacy safe from the scorn of their parents. Although the Regency TR-1 was the beginning of a revolution in music, it did not look the part. Making the modern radio modern was the task of Dieter Rams.

:focal(505x224:506x225)/https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/fa/ad/faad3116-d869-4962-8be9-c5ac7f5849c6/2008-14085web.jpg)

Rams is famous for saying, “weniger aber besser,” or “less is better.” His apparently simple designs are no so simple, they are in fact the result of complex thinking and eliminating all but the most necessary elements for the user. To come to a holistic simplicity, Rams had to think in terms of even the smallest factor. As he said, “My heart belongs to the details. I actually always found them to be more important than the big picture. Nothing works without details. They are everything, the baseline of quality.” After designing for twenty years, Rams published his famous Ten Principles, which are as simple and as straightforward as his designs and as timeless as his products. “I didn’t intend these 10 points to be set in stone forever. They were actually meant to mutate with time and to change. But apparently things have not changed greatly in the past 50 years. So even nowadays, they are still accepted,” he said, and, in fact, these Principles are often referred to as the Ten Commandments. One of his principles states in the words of Rams: “Good design emphasizes the usefulness of a product whilst disregarding anything that could possibly detract from it.” “Only well-executed objects can be beautiful,” he asserted, maintaining that good design is aesthetic, meaning that the design which is well executed is also its intrinsic purpose. To express that purpose, a good design has to be unobtrusive, rejecting decoration and deliberate artfulness. “Their design should therefore be both neutral and restrained, to leave room for the user’s self-expression,” Rams noted. When he said that design is “self-explanatory,” one immediately remembers that, as Rams explained, good design is timeless and honest.

Comparison between Rams on the left and Ive on the right

The difficulty of improving upon the design of Dieter Rams did not become obvious for fifty years. Other inventions made the transistor radio almost obsolete until in October 2001 when Apple introduced the new iPod, a portable music player–not a radio. Although its operation was different, the iPod, designed by Jonathan Ive, was based on the Dieter Rams principle “less is better,” and uses a rectangular shape with an inset circle (the dial or “click wheel”) and an inset square (the display screen). Not one superficial element intrudes. There is no need for a speaker for the user wears ear buds or personal speakers that are inserted in the ears. Following in the footsteps of Rams, Ive stated, “We wanted to get rid of anything other than what was absolutely essential, but you don’t see that effort. We kept going back to the beginning again and again. Do we need that part? Can we get it to perform the function of the other four parts?” For Rams and Ive, good design is not so much aesthetics–if the design is good, aesthetics will follow–as much is how it works–from the consumer’s perspective. In other words if the user cannot figure out the product then the design and the designer has failed. No instructions should be necessary. Ives remarked, “It became an exercise to reduce and reduce, but it makes it easier to build, and easier for people to work with.” In a 2015 article in The New Yorker, Ive explained, “I can’t emphasize enough: I think there’s something really very special about how practical we are. And you could, depending on your vantage point, describe it perhaps as old-school and traditional, or you could describe it as very effective.”

For his part, Dieter Rams has been very flattered at being thought of as the alpha of twenty-first century design, especially for Apple’s head designer Jonathan Ive. Both designers understand that the appearance of the design becomes the “brand” or the image of the entire company. The look of design must become one and the same with the corporation so that when one thought “Braun,” the image of the transistor radio would flash into the mind or when one said “Apple” in 2001, the memory of the iPod would be conjured up. Rams recently explained the significance of this identification: “Without doubt there are few companies in the world that genuinely understand and practise the power of good design in their products and their businesses. Probably the first example was Peter Behrens and his work for the German company AEG, in the early part of the 20th century. He might be considered to be the founder of corporate identity. Adriano Olivetti was close behind as he transformed his father’s Italian company, Olivetti.” For Rams, the term design is too closely allied to the idea of “beauty” or “aesthetic,” which is not his starting point. To stress the role of functionality in his work, the artist prefers using the German term, “Gestalt-Ingenieur.” Louis Sullivan would explain Rams’ philosophy and that of Jonathan Ive as “Form ever follows function.”

Therefore, it can be said, that design evolves but also advances, changing how we live, work, think and move. In a fast-moving contemporary world, design changes take decades and not centuries, but at a certain point the pattern is paused. A satisfaction point has been reached. This cessation takes place when the design seems “inevitable.” The potato chip chair of Charles and Ray Eames is, in its own fashion, perfect. This chair which has a rather more formal name, LCW (Low Chair Wood), was designed by the famous designer couple in 1946. The LCW has a simple curved seat set on simple arched legs, straddled wide for a supportive stance. The comfortable tilt back of the set delivers the sitter into the embracing back. Both scooped segments are plain bent plywood, an innovation perfected by the famous design couple. The two “chips” are the essence of “chair,” you sit and you lean back, you are supported and you are comfortable, you are satisfied with the bare but well crafted, thoughtfully designed and ergonomically considered, essential chair. There was no need to develop this piece of furniture further. Psychology is important to design; the designer and consumer reach that point together, a place where aesthetics and function and form merge and a universal configuration is achieved and a certain visual peace descends. At least until the next designer thinks of something entirely new. Today we live in a world created by new forms made during the opening years of twentieth century, when art and design were tasked with creating unprecedented objects for an unprecedented epoch. Many of these designs are still with us to this day. So, the question is when did the “modern” begin?

This series starts with the modern event that ended the long and lingering nineteenth century and initiated the twentieth century. The Great War of 1914 to 1918 changed the landscape of Europe and the mindset of all those who participated in it, from England to Germany to Russia to Turkey to America. Out of this war came, not just new ways of thinking about technology but also iconic new objects that demanded new designs, such as the first mobile phone. In other words, the Great War, as it was known at the time, was a line drawn in the sand; there was no going back to the old ways and the only path forward was to remake and redesign what was clearly a new world. The next twenty years were decades in which designers gave society its modern appearance, from clothing to kitchens to furniture—little was left unchanged. This surge of innovation was ended by the Second World War. The Interregnum was over, the Modern was defined by 1940 but the War would interrupt the further development of modernity and that year is when this series reaches its end-point.