Building a Concept

The Horseless Carriage

How did the 19th century automobile become the contemporary car? Manufacturer Henry Ford may have produced the first affordable car, available for the masses, but the Model T did not “look like” a car, it retained the characteristics of the carriage which had been drawn by a horse. Therefore, its progeny, or the first car, was called the “horseless carriage.” It would take decades for the automobile to acquire its modern appearance, which would define the look of a “car.” Designers searched for and found the form that followed its function. The “car” as we know its shape today was the result of a slowly developing effort on the part of numerous designers in several nations. Writing in a journal The Horseless Age: The Automobile Trade Magazine, in 1902, Robin Damon, described his journey to New York to see the newest “horseless carriages:”

Considerable interest appeared to be shown in the electric department, and especially by men who had been through the mill with either steam or gasoline or both. With increased knowledge of the properties of electric carriages more confidence is felt in their operation, provided the scope is not extended beyond well defined limits. One thing at least in favor of the electric vehicle is that the makers try to tell the truth about them. All acknowledge that they will not go at fast speed, and that the batteries must be taken care of to get results, while there did not appear to be any disposition to magnify the distance that could be accomplished on a single charge of the battery..A new thing in an engine to run with kerosene, used more like gasoline, was shown, and the engine certainly did revolve. This carriage was the only real departure from accepted styles in the automobile world..As to gasoline engines, I saw several new ones, and it may be just that I am prejudiced, but it struck me that the makers had not taken advantage of their opportunities, for instead of correcting the evils found in the old styles they had introduced new ones of their own invention.

The author was a witness to the new art and craft of inventing the horseless carriage, an innovative form of transportation barely twenty years old. Some of the same issues faced today over a century later were introduced by the author–how to propel the machine, gas or electricity? making a well-crafted “carriage.” He remarked at the end of the article that he had tried to warn prospective buyers that a horseless carriage was a difficult mechanical contraption but that the consumers could not fathom the difference between taking care of a horse and taking care of a car. He wrote, “..I heard many say there would be no trouble form anything. Buyers are apt to think that horseless carriage dealers are closely related to sellers of real horses when truth is considered. I am still watching for the carriage capable of carrying four people that can be used in all weathers and seasons. There are no indications that their carriage will appear this year.”

In the beginning, the automobile was a substitute for the horse and human locomotion. The new invention was noisy, smelly, a social menace, a novelty, an unnecessary addition to a world that had been getting along quite well by walking if you were poor or riding a horse if you were rich. the rudimentary roads, accustomed to horses and people and wagons, were deadly to the fragile wheels and flat tires were constant. Breakdowns were just as frequent and every driver had to be a mechanic. Who would want such an unpromising contraption when the horse was so ubiquitous and so reliable? Who could have imagined that a hundred years later, the horse would be relegated to the ranch and best seen at the races? But the vision of the horseless carriage was just the first step to the “car.” In his book, The Metallurgic Age: The Victorian Flowering of Invention and Industrial Science, Quentin R. Skrabec, Jr. began with a few well-conceived historical observations.

The automobile or horseless carriage, was the final product of the great Victorian engineers. It has been estimated that more than 100,000 patents combined to create the modern automobile. The history of the horseless carriage is one of definitions much as one of technology. It is a history of eliminating mammalian power for locomotion..The slowness of the automobile’s development was not from complexity, but more from lack of a vision or direction..The story of the horseless carriage begins in 1778 with the work of French military engineer Nicholas Joseph Cugnot. To Cugnot is given the honor of the first steam-driven carriage..One day in Paris, Cugnot lost control, and the resulting explosion led it to be banned from the streets.

What is interesting about this account by Skrabec is the point he made earlier–the definition of “horseless carriage.” In the eighteenth century, steam was the means of moving machines and it was natural that it would be applied to the new “carriage.” With hindsight, it is clear that the future of fuel could not be steam, but in for over a hundred years, the eclipse of steam was not foreseen. Even science fiction writers, such as Jules Verne, as Skrabec pointed out, assumed steam was the propulsion of the future. The author also recounted the early struggles with simply coming up with the best name for the new invention, writing about an 1895 contest with a prize of $500 offered by the Chicago Times-Herald. The winner was the New York Telephone Company which proposed “motorcycle,” which won over the word “automobile.” There was an actual race attached to this contest, including Benz inventions. “The day of the race there were only six vehicles, two of which were electrics. Of the four gasoline engines, three were Benz cars, and the other was a Duryea..The Duryea triumphed that day. The official report read, Three and one-half gallons of gasoline, and nineteen gallons of water were consumed. No power outside of the vehicle was used..Our correct time was seven hours and fifty-three minutes. We covered a distance of 54.36 miles–averaging a little more than seven miles per year.“

The First Automobile: Benz Patent Motor Car: The first automobile (1885–1886)

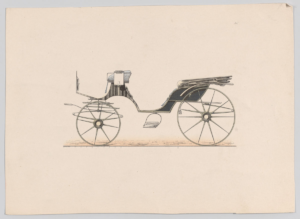

Horses and some version of a wagon were everywhere. The rural community was accustomed to hitching a ride on horse drawn carts and wagons. In the urban areas, the wealthy young men flaunted their horse drawn carriages. There was the “barouche,” an open summer conveyance which had a protective top which could be folded down and out of the way. Then there was the cabriolet, which unlike the four-wheeled barouche, had only two wheels. The landau was also open but had a two part folding hood, as these covers were called. Notice that some of these terms associated with carriages carried over to modern times. We now lift the “hood” of the car which is driven by “horsepower,” and there were cars named “cabriolet.”

French Design for Cabriolet Carriage (1880)

The new automobile was always thought of in terms of a substitute for a horse and the first cars were merely carriages sans horse. The early cars were small, compared to carriages, were vertical and open, lacking a windscreen or a protective covering for the face. Even with the precedent of the carriages and their hoods, its was a decade before the traveler, who was exposed to the elements, had even minimal protection. The early convertible top was folded down in pleats and rested at the back of the car and could be drawn forward when it rained, but was hardly convenient to operate. Unlike carriages which usually had coachmen to take care of the passengers, automobile drivers were on their own. Gradually more coverings, such as a stationary top, front and side windows, were added on to the automobiles which began to stretch out horizontally, sporting front and back seats. In the section “Phenography of the Automobile Form,” in the book, Designing Motion: Automotive Designers 1890 to 1990, Markus Caspers discussed the problem of form and shape of the “horseless carriage.”

Its provenance from the (horse-drawn) coach was an aesthetic problem for the automobile right from the beginning. By around 1900, the coach had become “old technology;” by contrast, the large-scale technologies needed for ships and aircraft were new and forward-looking. Even the bicycle with its socketed steel tubes and balloon tires represented a more trendy means of transport at the time of then Art Nouveau style..Faster, bigger, further–the Blue Riband for the fastest cruisers, the most luxurious steamers–these all inspired people’s fantasy at the time. Aircraft at this time were still clunky, scarcely clad skeletons, but they soon replaced ships as the icons of technology. This also affected automotive design. From the point of view of formal aesthetics and material technology, the motor car initially took its cues from the boat, because people could not conceive if as having its own form; however the shape was inverted–the pointed bow of the boat became the boat tail, that is the pointed end of the auto body. The change of form until Mercedes Benz had the idea, in 1913, to kink the radiator/its housing and thereby place it dynamically more beneficially to face the airflow. For more than half a century, the automobile’s underlying technology concept relied upon “borrowed identities..”The shape of ships was investigated scientifically; laboratory-based research into fluid mechanics started. But it took quite some time until contemporaries recognized that a car too has to overcome air resistance, and that the function of the body shell is not just to protect the passengers and luggage against the effects of the weather, as as the case with the horse-drawn coach.

Packard Motor Car Company Automobile 1910

In 1916 a man named Victor Page, who had owned a Ford Motor car for four years, wrote an instruction manual for owners who would have to fix and repair and otherwise care for their vehicles entitled, The Model T Ford Car, Its Construction, Operation and Repair. But sadly is innovative book would be superseded when Henry Ford the inventor of the idea of an “affordable car” that everyone could own and drive, decided upon a final design: The Model T, which had been a work in progress for years. From 1909, the Model T had been manufactured and became a hit with the American consumer. As historian Lindsay Brooke pointed out, one would have to wait a year before receiving a Carmine Red or a Brewster Green or the gray Runabout. There was a ton car and a landaulet to add to the open body Touring car. For a number of years, Ford experimented in various models, learning along the way until in 1922, he wrote that “Buyers are learning how to buy.” He felt that those who purchased cars were seeking quality. Ford continued that the manufacturer should produce “the very highest quality and sellout the very lowest price, you will be meeting a demand which is so large that it may be called universal.” The author of Ford Model T: The Car That Put the World on Wheels continued,

So, on that spring day, the self-taught practical engineer and commonsense businessman set in stone his visionary plan for the ‘universal car’ that would soon transform personal mobility and, with it, modern society. As he later recalled “I announced one morning, without any pervious warning that in the future, we were going to build only one model was going to be the Model T, and that the chassis would be exactly the same for all cars.” Unquestionably from that point on the Model T, offered in multiple body styles, would be the company’s only product..none of the men with Ford that day..could imagine that 18 years would pass before Ford introduced an all-new model!

Henry Ford’s mass produced Model T cars rolled off the new assembly line, pumping out new transportation that everyone could afford. The car followed the basic design established by the carriage–it was vertical and black, but the sheer numbers that were manufactured began to pressure society to respond to the presence of more and more automobiles in its midst. Everything from roads to tires to public safety needed to be rethought and through decades of adjustment, the world finally gave way to the demands of the automobile. One of the interesting consequences of Henry Ford’s revolution in the mass manufacture of automobiles was a concept called “Fordism.” “Fordism” was somewhat like “Taylorism” the invention of Frederick Taylor who broke down the motions of a worker into small units. Taylor sought to make the worker’s process more “rational,” one of the key words of the early twentieth century, and therefore more efficient. Ford, however, introduced the assembly line, or the breaking down of the object itself into multiple units which were then put together by a team of workers on the line. Part of Fordism was the teamwork among the employees who were well paid by their boss, who wanted them to purchase the product itself. Hardly a friend to labor, Ford, nevertheless, knew how to create descendants were the cars of the people of America. But there was an altogether different type of vehicle sharing the road with the familiar black Ford, something we might think of as the High End version of Ford’s little car.

As with the fancy carriages, such as the barouche, automobiles were for the wealthy. They were relatively rare, too expensive for the middle and lower classes, but as the century progress, their numbers continued to climb and more thought began to be poured into the design. At first, design was a matter of ostentation–the automobile as an advertisement of wealth and privilege. The vehicles of the 1920s were festooned with embellishments, such as running boards, a spare tire near the front fender, multiple headlamps and so on. The automobiles were still horseless carriages in concept–they were simply stretched out and lowered. It would take four decades for cultural thinking to re-think the automobile as a unique vehicle in its own right with its own destiny and its own needs and its own definition. The post war Rolls-Royce was an elegant car, deliberately designed for the very few and the very wealthy. Henry Royce who was responsible for the design wrote of the very special role of the Rolls-Royce: “It is difficult to see the position of the luxury car after the war. One has the impression that there will be somewhat limited use for such a car, probably more limited than before the war.” The company was challenged by the mass manufacturing from America after the war. In fact, in the book Rolls-Royce: The Years of Endeavour, Ian Lloyd wrote, “..the industry was relatively quick to respond to one important misjudgment of the market. In the 1919 Pairs Show there was a preponderance of large and costly cars most of which showed very little change from pre-war practice..By the 1921 Olympia Show this preponderance had vanished completely. At this Show there were a large number of very small cars. This was no doubt due both to the depressed economic climate and extensive imports of low-priced, quantity-produced vehicles from the United States in 1920 after import restrictions imposed during the war had been raised.”

It was in the post-war period that it can be said that there were enough automobiles and enough drivers for certain expectations to have emerged. Consumers understood the intent and limitations of the Ford products and they would expect more of expensive models such as the Rolls-Royce. The post-war Rolls was style heavy and performance light and the company knew that drivers disliked being overtaken by cheaper cars. As Peter Pugh wrote in his book, Rolls-Royce. The Magic of a Name. The First Forty Years of Britain’s Most prestigious Company 1904-1944, “..in 1922 the directors took the decision to invest in a new car..Sales slumped in 1921 and 1922..In 1922 only 430 were sold, less than a quarter overseas..By 1925, the New Phantom (retrospectively called Phantom I when Phantom II was introduced in 1929) was ready. it replaced the Silver Ghost beating its performance and re-establishing Roll-Royce’s lead as the manufacturer of luxury cars..The new model had been prepared with great secrecy, and during its development had been codenamed EAC (Eastern Armoured Car).” The code name referred to an actual Rolls-Royce armoured car manufactured during the Great War and used in the Middle East. This new car impressed Detroit with its ability to run a track at 80 miles per hour. By 1929, there was a new Phantom II with a completely new chassis.

It was the plan of the Rolls-Royce company to set itself apart from the mainstream American companies that mass-produced cars for the average customer. “The name Rolls-Royce had become synonymous with superior engineering design and the highest possible quality. Henry Royce believed that a large mass-market-oriented firm could not have achieved the same results as Rolls-Royce, in which the work was carried out by small teas of creative, highly skilled and motivated employees. Thus, the way for Rolls-Royce to compete in the age of mass production was to place even more emphasis on quality while also working to cut costs. Royce believe that design engineering was the function that added the most value to Rolls-Royce’s products..Royce’s strategy was profoundly different from that of contemporaries such as Alfred Sloan at GM, because it involved using a minimum of capital rather than the maximum that could be utilized efficiently. There was one area, however, where Royce was determined to spend as much as possible: research and development.” In the book on Creating Modern Capitalism. How Entrepreneurs, Companies, and Countries Triumphed in Three Industrial Revolutions, Peter Botticelli, continued noting that the accomplishments and strategies of Rolls-Royce were possible only in England. He quoted Royce as saying, “..in England, with our small output, our only chance is that our production must stand out by all-around perfection, rather than price..”

By the 1930s, there were clearly demarcated arenas of automotive production: mass production for the ordinary customer and luxury production, deliberately limited and carefully crafted, for a small group of privileged people. The design, however, remained stubbornly fixated upon the “horseless carriage.” Changing the look of the the automobile and re-imagining it into the modern “car,” did not happen in England or America, rather the next changes took place in the East, especially in Germany. What happened in Germany was two-fold, building roads for cheap mass produced cars to drive on and redesigning the cars to recognize the need for an aerodynamic shape. Re-imagining the automobile was a thought process of the 1930s, when everything, every conceivable object, became streamlined. Inspired by the increasing speed of transportation—the fast trains, the fast airplanes, the fast ships, designers began to re-think the car, eliminating the horse at last, and re-imagining in terms of flight. But how did the slow moving car–slow in relation to trains and airplanes–come to be thought of in terms of speed? When I use the word “speed,” I want to make a distinction between the idea of an automobile being faster than a horse and a car that felt like it was flying, zooming through the air, streaking across the countryside. The roads of the 1920s did not allow such driving. Based upon existing paths, the first roads often retraced trails carved out by animals pulling wagons or, in the case of Atlanta, Georgia, followed the paths of cows meandering towards their various barns. These early streets were narrow and crooked, rutted and often unpaved, cluttered with a mixture of vehicles, from wagons to cars, horses and pedestrians. For most people, driving fast was more of a fantasy than a reality, but in Weimar Germany the government decided to build an Autobahn–no horses, no carts, just fast cars. The next post will discuss the invention of the modern car: a dream that would not come true for twenty more years.