The End of the World: Ludwig Meidner and the Apocalyptic Paintings

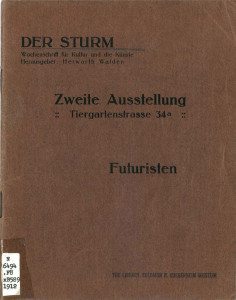

The avant-garde arrived late in Germany. Not only was modern art late, it also landed in the cities of Germany unchronologically, in bits and pieces, entirely lacking sequence, reft of developmental lines. The German artists, confronted with the smorgasbord of French, Dutch, Norwegian, and Italian artists, sampled and selected what they chose, repositioned the works for their own devices and reinterpreted their meaning for their own purposes. The muddled Modernism could not be helped. For all intents and purposes, avant-garde art had begun in Paris and spread east to great effect in Russia and Germany. Neither of the recipients, the artists of Moscow or the artists in Berlin, were disturbed over the disorder, and, it must be said, the French, being French were equally unperturbed. Selling to eastern patrons was a business conducted by their dealers and the French artists were happy with the proceeds. The Italian artists were also belated on the German scene/s. The year 1912 was the debut year of Italian Futurism as a visual art, with shows of Futurist artists traveling from Paris, where they were scorned, London, where they were reviled, and Berlin, where they were badly hung, mixed in with other “modern”artists whose work was totally incompatible with Futurist goals and aims. But the ideas of Futurist art was also uniquely suited to to Berlin.

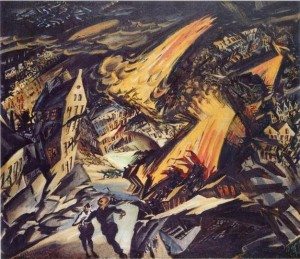

Ludwig Meidner. Apocalyptic Landscape (1912)

Like Italy, Germany was riven with regionalism, like Italy, Germany became a nation late in the game, and, like Italy, Germany industrialized decades after Great Britain. In The Visual Arts in Germany 1890-1937: Utopia and Despair (1988), Shearer West wrote that “Germany’s industrial revolution came later than that of some other European nations, but it was also quicker and more effective. Unlike Italy and France,where rural peasant traditions lingered long after urban modernization, Germany had become a wholly modern industrial nation by the First World War. Certainly many artists and writers were enthusiastic about the possibilities of a modern Germany, and particularly the growing metropolitan culture which seemed to open up possibilities for new ways of life. But the enthusiasm for the city that colored the rhetoric of such Futurist empathizers as Ludwig Meidner was the exception, rather than the rule.” As shall be seen, the term “enthusiasm” is perhaps not quite on the mark, for the German artists were, as a whole, more interested and concerned and critical of the metropolis, than excited. To mark a middle path, it would be fair to say that both the Germans and the Italians were fixated on the city, albeit for very different reasons.

Umberto Boccioni. The City Rises (1910)

For most of the nineteenth century, the French were behind the English in modernization, but France had, over time, begun to catch up. In contrast, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the Futurists were reacting to the sudden onset of modernity, accepting and glorying in all of its promises. The shared “future shock,” or what art writer Robert Hughes famously termed, “the shock of the new,” made Berlin a very compatible place for Futurist artists to exhibit. Futurist painting displayed anarchist themes and called for social uprising, delighting in the pace and speed of all things that mechanization had put in motion. The German artists, both visual and literary, responded to the underlying theme of Futurists, the sudden appearance of a new way of life. They shared, with the Futurists, a contempt for the bourgeois way of life and Bürger conventions and middle class conventions. Regardless of how well or badly Futurist art was displayed in its Berlin debut, the German artists of 1912 were prepared to be intrigued.

Wherever there was an exhibition of Futurist art, there would be a performance from the leader of the pack, Fillippo Tomasso Marinetti (1876–1944), the high energy impresario of renegade poetry and words running about in freedom. Unlike their receptions in Paris and London, the Futurists had a champion and support in Berlin: Herwarth Walden (1878– 1941), easily a match for Marinetti in energy. From the standpoint of artists and poets, Walden was in (1910-32) charge of the most visible game in town, the journal Der Stürm for the poets and the Galerie Der Stürm (1912-32) for the artists. Founded in 1910, the German literary journal was perhaps the successor to Marinetti’s magazine for medical poets, Poesia, founded in 1905 and, having become obsolete and old fashioned, folding in 1909. The journal, which published cutting edge “expressionist” poetry, also printed reproductions of avant-garde art, including international as well as German works. Walden supported the powerful critiques of the city of Berlin and Wilhelmine life from the poets of the Neue Club, again perhaps entering into the political phase of activist art, urged by Poesia, which published the Manifesto politico futurista (Futurist Political Manifesto) in the last issue. However close the intellectual concerns of the Futurist artists and writers were to their counterparts in Berlin, as can be seen, German Expressionist poetry preferred the old fashioned stanza approach, compared to Marinetti’s “words in freedom.”

God of the City (Der Gott der Stadt)

1910

Georg Heym

Upon a block of houses he sits wide.

The wind encamps all black around his brow.

Irate he stares, where in far solitude

Stray beyond the fields some last few houses.

At evening glows the ruddy gut of Baal,

The greatest cities kneel to him like choirs.

A monstrous heap of church bell after church bell

Up to him swells from dark a sea of spires.

The music drones a Corybante dance

Of millions ambling loudly through the streets.

The chimney smoke, the clouds of manufacture

Unto him cling, blue scent of incense sweet.

The weather smolders in his eyebrows twain.

The dark of evening unto night is dulled.

The storm winds flutter, like great vultures gazing

From out his great locks, in his wrath all horrid.

His butcher fist into the dark he soars.

He shakes it so. A sea of fire hunts

The length of one street. And the hot smoke roars

Consuming it, until the morning comes.

Heym’s poem coincides with the paintings of Ludwig Meidner (184-1966) and with the rising social and political discontent in the city of Berlin. As early as 1909 Hans Kampffmeyer wrote “The Garden City and its Cultural and Economic Significance,” warning about the sudden growth of the city: “There then emerged the vast range of problems that we summarize under the single heading of “The Social Problem”–none of which can be understood without its wider context..One of the greatest dangers of the modern city is the increasing alienation of its inhabitants from nature. Elevating its occupants four and more stories above the surface of Mother Earth, the tenement house takes them farther an farther away form the open countryside end sets up more and more rampart of masonry between them..Only an arduous railroad journey can take us into the open air..” Kampffmeyer’s concerns, not uncommon for that time, went unheeded. If the German state was inclined to put money anywhere in the years before the War, it would be towards the military not towards the poor. This is the context of the Futurist Exhibition in Berlin, where cross currents of nationalist preoccupations with violence, war, political uprisings and unrest coincided and collided.

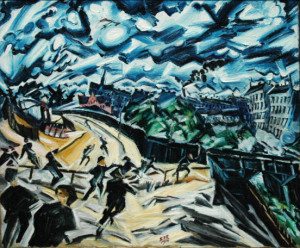

Ludwig Meidner. Apocalyptic Landscape (1913)

In conjunction with the 1912 Futurist exhibition at his Galerie at Tiergartenstrasse 34 a, Walden published Marinetti’s 1909 Futurist Manifesto in Der Stürm. The poetic manifesto, written with typical Marinetti excess, was psychologically in tune with the German mindset, with phrases like, “We will glorify war—the world’s only hygiene—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman,” echoing the extreme poetry of a Georg Heym. Marinetti’s writing, like that of the German Expressionist poets, echoed the rhythms of the nineteenth century American poet, the influential Walt Whitman: “We will sing of great crowds excited by work, by pleasure, and by riot; we will sing of the multicolored, polyphonic tides of revolution in the modern capitals; we will sing of the vibrant nightly fervor of arsenals and shipyards blazing with violent electric moons; greedy railway stations that devour smoke-plumed serpents; factories hung on clouds by the crooked lines of their smoke; bridges that stride the rivers like giant gymnasts, flashing in the sun with a glitter of knives; adventurous steamers that sniff the horizon; deep-chested locomotives whose wheels paw the tracks like the hooves of enormous steel horses bridled by tubing; and the sleek flight of planes whose propellers chatter in the wind like banners and seem to cheer like an enthusiastic crowd.”

More than any other artists in Berlin, Ludwig Meidner, was the visual counterpart of Futurism, both paintings and poetry, and German Expressionist poetry, acting out the prevailing mood of anxiety that was characteristic of the atmosphere of Berlin. In 1912, Meidner frequently contributed to the other outspoken journal of political critique, Die Aktion, founded in 1911 by Franz Pfemfert (1879-1954), who intensely disliked the machinations of unfettered capitalism. After the War, Pfemfert evolved into from a promoter of literary expressionism, abandoning aesthetics in order to become a supporter of radical democratic socialism, preferably by revolution. In the pre-war years, the journals, Die Aktion and Der Stürm, and the artists and poets featured in their pages, shared similar concerns. The rural themes of back to nature so relevant in the early Dresden years of Die Brücke disappeared when the artists moved to Berlin in 1911. Immediately the style radically metamorphomized–and this change can be best viewed in the paintings of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938), who abruptly abandoned his Gauguin-esque landscape works and appropriated the jagged shards of Cubism to respond to the shape of life in the city. For the Berlin artists and poets, the city itself was the all-absorbing theme, leading to a new genre of art, Großstadtlyrik (big city poetry). According to the article “Provocation and Parataxis” by Mark W. Roche in A New History of German Literature (2004),

“Poets drew on smells, sounds, modes of transportation, commerce, technology, and the bustle of city life for poetic themes. The city was portrayed as both daemonic and dynamic. As in painting, so in poetry, the modern metropolis was feared and criticized, but was no less a source of fascination. City life alienates and poisons; it is impersonal and materialistic, yet also vibrant and multifarious..Related to the theme of the metropolis is technology. While technology seems to carry a life of its own, the individual becomes increasingly an object, without life or soul.”

In understanding the social conditions in the city of Berlin and Meidner’s apocalyptic visions of the city, it is important to note that not only did this urban area explode in population but industry was also situated very close to the city’s edges to best capture the thousands of workers drawn to the new environment. Unlike London, where one could take a quick train ride to a bucolic suburb, Berlin was hemmed in. Meidner, who had migrated from Silesia to Berlin, would have watched the factories of Siemans, a firm to become notorious in the Second World War, expand in the Spandau suburb, wiping out the countryside. But more then the abrupt transformation of once quiet landscapes into vistas of chemical factories and mass housing, it was the possibility of an urban uprising, a revolt of the proletariat that aroused the interest of Meidner. Living in poverty and residing mass housing, he was very attuned to the political concerns of the lower classes. While his poet counterparts wrote about violence and rebellion, Meidner, who, unlike them, did not come from a privileged background, was impatient with middle class armchair critiques. He wandered the streets during the sweltering summer of 1912, the hot and heady summer of Futurism, walking among the misery of the poor. According to Jay Winter in Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in European Cultural History, Berliners wondered which could take place first, an international war or a rebellion against the Kaiser, who–incidentally–was perfectly willing to shoot all resisters. Although Winter questioned the extent to which Meidner’s paintings were prophetic of a coming war, he does note that there were several works that predict war and notes that Meidner was impacted by the poetry of Heym.

Like the poems of Heym, the paintings of Meidner were read “backwards” after the War as premonitions or predictions of the Apocalyptic end of the world, but Winter argued that “..the central conflict on the agenda in 1911-14 was the potential for class war, not the gigantic clash of European warriors..Berlin was teeming with tenements, or human barracks-Mietkasernen in German. Mender lived among them, in the belly of the whale..the environment of domestic political conflict, and in particular class conflict, was sufficiently overheated to supply these artists with more than enough ominous material for their eschatological explorations..” Explaining how to paint the modern city in his own words, in 1914, Meidner published “Anleitung zum Malen von Grossstadtbildern” or (“Instructions for Painting the Metropolis”) in Kunst and Künstler, a remarkably dry text that was literally what it said–instructions. There was little of the emotions or the expressions supposedly characteristic of these intense artists. But Meidner does talk about the formal or visual characteristics of the modern city with excitement:

“The angular lines of which we are speaking—principally applied as they arc in graphic art should not be confused with the lines traced upon a building plan with the aid of a mason’s triangle. Never believe that the straight line is something cold and rigid! You must simply draw it with enough excitement and properly observe its flow. It should be now thin, now thick, trembling gently with nervous excitement. When we look upon our cities, what do we see but battles of mathematics? See what triangles and circles and polygons assault us in the street. Rulers are flying off in all directions. We are pierced on every side by angularities. Even the moving people and animals appear like geometrical constructions.” Meidner then both acknowledged and refuted the debt owed to the Futurists by saying, “The manifestos of the Futurists—though not their actual foolish creations —have shown us where the problems are..” meaning that the Futurists celebrated the city and the Berlin artists understood it as a savage entity.

1912 Exhibition Catalogue

Regardless of how Meidner and Heym and other apocalyptic poets and artists are interpreted today–as social critics or as visionaries who foresaw a horrible future–what is clear is that the years just before the Great War in Germany were not as sweet as those of the Belle Epoch experienced by other nations. The nation was on a knife edge, and in perusing the social history and the political unrest present in the large cities, such as Berlin, immediately before the summer of 1914, it seems that Germany was particularly tense and that everyone was waiting to see what would break out first, a political rebellion or a world war. Meidner’s roiling and restless cityscapes, dark and unspeakable in their premonitions the horrors to come, spoke not just to the grim possibilities facing the German people and to the probable outcome–the end of the world.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.