The Coming Apocalypse: Ludwig Meidner and the Poets

In the winter of 1912, the German poet Georg Heym fell through a hole in the ice and drowned. The strange death of the twenty-four year of poet was surrounded by an odd mixture of conjecture and fact. It was thought that on January 16th, he was attempting to rescue his friend, Ernst Balcke, also a poet, who had plunged into the icy waters of the river. This assumption was based upon the apparent fact that Heym was able to hang on to the edge of the ice and shout for help, his cries reaching foresters working at the banks of the Havel. For some reason, the woodsmen were unwilling to lend their ropes or ladders to help one of the poetic geniuses of twentieth century poetry. Eventually Heym’s fingers slipped off the ice and he sank to his death. When the two bodies were recovered two days later, it was unclear whether Blaeke and Heym, two poets on a skating trip, died from drowning or hypothermia. In his 1971 article,”Ogling through Ice: The Sullen Lyricism of Georg Heym,” one of Heym’s English translators, Peter Viereck reported that when his friends saw Heym in his coffin, he was still frozen enough for his features to have retained “The bitter expression of his lips, twisted by the horror of fifteen minutes of continuous screaming for help to onlookers.” What makes the death of Heym even more eerie is that he dreamed that he would die by falling through the ice and in 1910 wrote down his dream, a dream that horribly came true, but without the happy ending:

I found myself standing on the banks of a great lake which seemed to be covered with a type of stone coating. It struck me as a sort of frozen water. On occasion it seemed to be like the sort of skin that forms on top of milk. Some people were moving on the lake, people with bags or baskets, perhaps they were going to market. I ventured a couple of steps, and the plates held. I felt that they were very thin, since as I stepped upon them they swayed back and forth. I had gone for some time and then a woman encountered me, who cautioned me to turn back, the plates would soon break. But I persisted. And suddenly I felt that the plates were dissolving beneath me, but I did not fall. I proceeded further, walking upon the water. Then the thought occurred to me that I might fall. In that moment, I sank into green, slimy, kelp-infested waters. Still, I did not feel lost, I began to swim. As though by a miracle, the shore, though first distant, drew closer and closer, and with a few strokes I landed in a sandy, sunny harbor.

Georg Heym (1887-1912) wasn’t the only prophet who was having dreams. A year later, Carl Jung (1875-1961) also had a prophetic dream, one he dreamed three times. In October 1913, a year after the death of Heym, Jung reported in his book, Memories, Dreams, Reflections,

..while I was alone on a journey, I was suddenly seized by an overpowering vision: I saw a monstrous flood covering all the northern and low-lying lands between the North Sea and the Alps. When it came up to Switzerland I saw that the mountains grew higher and higher to protect our country. I realized that a frightful catastrophe was in progress. I saw the mighty yellow waves, the floating rubble of civilization, and the drowned bodies of uncounted thousands. Then the whole sea turned to blood. This vision last about one hour. I was perplexed and nauseated, and ashamed of my weakness.

Two weeks passed; then the vision recurred, under the same conditions, even more vividly than before, and the blood was more emphasized. An inner voice spoke. “Look at it well; it is wholly real and it will be so. You cannot doubt it.” That winter someone asked me what I thought were the political prospects of the world in the near future. I replied that I had no thoughts on the matter, but that I saw rivers of blood.

I asked myself whether these visions pointed to a revolution, but could not really imagine anything of the sort. And so I drew the conclusion that they had to do with me myself, and decided that I was menaced by a psychosis. The idea of war did not occur to me at all.

Soon afterward, in the spring and early summer of 1914, I had a thrice-repeated dream that in the middle of summer an Arctic cold wave descended and froze the land to ice. I saw, for example, the whole of Lorraine and its canals frozen and the entire region totally deserted by human beings. All living green things were killed by frost. This dream came in April and May, and for the last time in June, 1914.

In the third dream frightful cold had again descended from out of the cosmos. This dream, however, had an unexpected end. There stood a leaf-bearing tree, but without fruit (my tree of life, I thought), whose leaves had been transformed by the effects of the frost into sweet grapes full of healing juices. I plucked the grapes and gave them to a large, waiting crowd…

On August 1 the world war broke out.

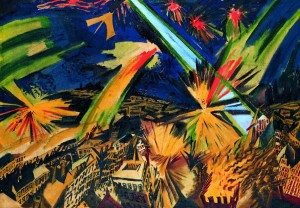

Ludwig Meidner. Apocalyptic Landscape (1913)

The coming of the war, known later as the “Great War,” had been foretold by astrology, Biblical prophecies, individual dreams, art and poetry. Georg Heym wrote his best poetry in the year of his death and these poems of a few months reflected the apocalyptic mood that had descended over Germany just before the Great War. He was part of a group of like-minded young poets, seething with rebellion and disgust for the bourgeois life in the “miserable Prussian shitstate.” He longed, as did many of his generation for a war, complaining, “If only someone would start a war, it needn’t even be a just one.” He was part of the loosely organized group of Expressionists who drifted in and out of Berlin, writers, poets and artists, all of whom were questioning the stultifying Wilhemine society in the famous Neue Club, a quarrelsome group of new poets who met at the avant-garde gathering place, Café des Westens. The 2012 article, “Apocalypse Then: Georg Heym & the Art of Cultural Divination,” noted that Heym was one of an even smaller and more radical splinter of the Club that broke and became part of Neopathetische Cabaret, more or less organized by Jakob Van Hoddis (1887-1942). Heym, fascinated with the doomed French Revolutionaries, Robespierre and Danton, was remembered by Dada artist, Emmy Hennings as “half bandit… half angel.” The poet Alfred Lichenstein (1889-1914) was also a member of this loosely composed group of Expressionists, transfixed by a somewhat undigested stew of Nietzsche, Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch, Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud, and even the writings of Sigmund Freud, all overseen by the overarching patronage of Herwarth Walden’s gallery and journal, Der Stürm. Heym, Van Hoddis and Lichtenstein all wrote poems, half-mad with tormented dreams of disaster, and all came to tragic ends. Lichenstein died in the second month of the First World War he had foreseen, Van Hoddis, a friend of the artist, Ludwig Meidner, went mad, was placed in a Jewish care home, from which he and his fellow inmates were taken and put to death by the Nazis at Sobibor in 1942, and Heym was quite forgotten until someone one noticed, after the Second World War, that he may have predicted the carpet bombing of cities.

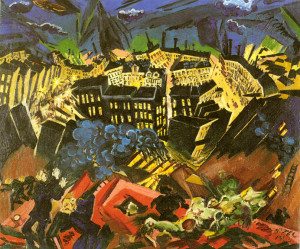

Ludwig Meidner. Burning City (reverse) (1913)

One of the problems of translation–whether of poems or paintings–is interpretation. Choosing the right words or the precise turn of phrase to create a consistency of meaning between languages is one thing, but understanding the work of art in its own context is yet another necessary element in comprehending its original meaning. The apocalyptic paintings of Ludwig Meidner (1884-1966) imagined the destruction of the city, probably the city of Berlin, where he lived..uneasily. His works precisely parallel the poems of the poets who mingled freely with the artists at Café des Westens. It is no coincidence that he formed the counterpoint of the poets’ Neopathetische Cabaret, Die Pathetiker, for visual artists. What makes these two linked and distinct bodies of art particularly complex is that their meanings were historically divided. Before the war, the paintings of Meidner were commentaries on the rapidly changing city of Berlin, newly modern and oppressively modern. After the “Great War,” such works became retroactively apocalyptic, predictive of things to come, of events that arrived. During the same years as Heym, Van Hoddis and Litchenstein were writing their apocalyptic poems, Meidner was painting his apocalyptic landscapes. Van Hoddis’ poem End of the World (1911) is often credited with setting off a series of powerful and extremely visual poems, but what did they mean? Imagining the destruction of what–the cramped middle class world the poets protested against–the newly crowded and modern Berlin–the aging civilization of the Belle Epoch, the lingering decadence of the nineteenth century? In its eight lines, Weltende called for an end, a deluge, a destruction of anything and everything.

World’s End

1911

Whisked from the Bourgeois’ pointy head hat flies,

Throughout the heavens, reverberating screams,

Down tumble roofers, shattered ‘cross roof beams

And on the coast – one reads – floodwaters rise.

The storm is here, rough seas come merrily skipping

Upon the land, thick dams to rudely crush.

Most people suffer colds, their noses dripping

While railroad trains from bridges headlong rush.

Translated by Richard John Ascárate

Written two years later, Litchenstein’s Prophecy, a bit longer and no less violent, appeared. The young poet would be killed a year later, early in the war, as his poem seems to predict. Ironically he died on a piece of land that would be retaken by British troops, a company which included the poet Wilfred Owen, fighting for the soil where Litchenstein had fallen. What is clear, in reading these foretelling poems, is the difference between Expressionism in Berlin and that of Murnau, where Vassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) and Franz Marc (1880-1916) were exploring a very different version of this broad movement. Kandinsky and Marc both painted the end of the world and even wrote poetry about the end of time, but their end is more of a spiritual apocalypse, a collapse of a psychological state of yearning for a better world. Their paintings, rendered on the verge of a conflict, reflected the social uneasiness and cultural impetus towards an event or events that would end the ordered world of international exchange among the artistic fraternity. In Berlin, the dis-ease was more related to the social, cultural and political changes rippling across the capital. The “apocalypse” in all of these poems was material and real, just as Meidner’s landscapes were illustrative and representative of imagined horrors to come–the destruction of cities (Berlin) and perhaps the future to come.

Prophecy

1913

Alfred Litchtenstein

Some day – I have signs – a mortal storm

Is coming from the far north.

Everywhere is the smell of corpses.

The great killing begins.

The lump of sky grows dark,

Storm-death lifts its clawed paws;

All the lumps fall down,

Mimes burst. Girls explode.

Horses’ stables crash to the ground.

Not a fly can ecape.

Handsome homosexuals roll

Out of their beds.

The walls of houses develop fissures.

Fish rot in the stream.

Everything meets its own disgusting end.

Groaning buses tip over.

Of course, whether referring to poetry or painting, the term “Expressionism” is a highly problematic one and is especially confusing when it is recalled that manifestations of the movement in Germany differed from city to city, from region to region, and from artist to artist. It is safe to say that in Berlin, the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) were appropriated by the artists and poets for their own purposes, while in Dresden his ideas were seized upon for very different reasons. And as has been seen, the situation among artists in Munich was unique to southern Germany. The contrasts were one of political revolution where the Übermensch would overthrow tradition and the elevation of Dionysus, where the irrational and the emotional would overthrow the reasonable and logical, existing among the many interpretations of the writer in a relatively new nation, composed of many principalities. The philosopher was, for the artists in general, a renegade voice, one of the many critical tools that they could pick up in their generational war with the conventional. In its own way, Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks: The Decline of a Family (1901) was as powerful an indictment of German society–not to mention a more recent and pertinent critique–as the clarion calls of Nietzsche for an overthrow of the old order. But, according to Neil H. Donahue in his 2005 book A Companion to the Literature of German Expressionism, Mann disapproved of Expressionism: “We should recognize however that inherent to the Expressionist tendency in the arts there is an intellectual impetus to do violence to life.”

Ludwig Meidner. Apocalyptic Landscape (1913)

Given the fragmentation of “expressionism” in Germany, the term has limited use. Expressionism, essentially an art dealer designation, today refers to the pre-war period in art and literature. Expressionism in Berlin was more linked to “modernism” than the version of Expressionism in either Dresden or Munich. Modernism, in Berlin, was Janus-faced, both utopian and destructive, laden with the fin-de-siècle pessimism and despair that was an international response to industrialization and the new technology that was both the beginning and end of a new era, the shape of which could not be foreseen–except as struggle and dark madness. Poetry and the paintings of slice of time before the world tilted into the abyss were full of violent forebodings. The posthumously famous poem, War, by Georg Heym became the hallmark of these years of nervousness.

War

1911

Georg Heym

Risen out of vaulted places dark and deep.

In the growing dusk the faceless demon stands,

And the moon he crushes in his strong black hands.

In the nightfall noises of great cities fall

Frost and shadow of unfamiliar pall.

And the maelstrom of the markets turns to ice.

Silence grows. They look around. And no one knows.

Something touching them in side-streets makes them quail

Questions. There’s on answer. Someone’s face turns pale.

Far away a peal of church-bells trembles, thin,

Causes beards to tremble around their pointed chins.

On the mountains he’s begun his battle-dance,

Calling: Warriors, up and at them, now’s your chance!

There’s a rattling when he shakes his brute black head

Round which crudely hang the skulls of countless dead.

Like a tower he tramples out the dying light.

Rivers are brim-full of blood by fall of night.

Legion are the bodies laid out in the reeds,

Covered white with the strong birds of death.

Ever on he drives the fire and nightward-bound,

To the screams that come from wild mouths, a red hound.

Out of darkness springs the black domain of Nights,

Edges weirdly lit up by volcanic lights.

Pointed caps unnumbered, flickering, extend

Over the satanic plains from end to end.

And he casts allfleeing things down on the roads

Into fiery forests where the swift flame roars.

Forests fall to the consuming flames in sheaves,

Yellow bats whose jagged fangs claw at the leaves.

Like a charcoal burner in the trees he turns

His great poker, making them more fiercely burn.

A great city quietly sank in yellow smoke,

Hurled itself down into that abysmal womb.

But gigantic over glowing ruins stands

He who thrice at angry heavens shakes his brand.

Over storm-torn clouds’ reflected livid glow

At cold wastelands of dead darkness down below.

That his hellfire may consumer this night of horror

He pours pitch and brimstone down on their Gomorrha.

Translated by Patrick Bridgwater

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.