Irish Artists at War

Part Two

William Orpen (1879-1931)

Orpen in Flanders

What would it take to make an Official War Artist go rogue? At the end of the Great War, Irish artist, William Orpen was asked to remember the sacrifices of the British Army, albeit, in an appropriately “official” manner and what the delivered was a painting that was not just unofficial but decidedly a condemnation of the War itself. The painting Zoonebeck would have been a warning shot towards the bow of the government’s narrative of the War. Zoonebeck, in Flanders, was the site of a successful British assault on the German lines at Passchendaele, another of the prolonged battles of the Great War, this one extending from June to November of 1917. Gains were eroded by pounding rain, which turned the fields into seas of mud, often clouded by poison gas, ultimately utterly destroying the village. The success was eventually defined as a five mile push forward by the British at a cost of 250,000 lives, one of which was memorialized by Orpen. A sprawled dead body, a fragments of a dead tree, a pockmarked and blasted dead landscape, all colored in the khaki dun mud colors that would characterize this tragic war–indicating that Orpen might not be the artist to whom you want to grant a major commission, even Major Sir William Newenham Montague Orpen, KBE, RA, RHA.

William Orpen. Zonnebeke (1918)

To be fair, Orpen’s early career and his government connections gave every indication that he understood his role. Educated at Slade, that remarkable art school that produced so many of the fine artists of the Great War, Orpen, like his Irish counterpart and friend, John Lavery (1856-1941), was a well-connected portraitist, who had cast his lot with the English. He resisted the pressure to take a stronger stand for Ireland after the Easter uprising in 1916 and began, instead, to attempt to be shift his duties as a clerk in the Army Service Corps to the Front. Bypassing the Department of Information, the site of the Official War Artists, Orpen began his journey after pulling the many strings that the artist was able to access, including the all-important connection to the commanding general Douglas Haig. Most artists were give the polite rank of second lieutenant and allowed to stay at the Front only a few weeks but Orpen was dubbed a “Major,” by Haig, was given a entourage of assistants, and was allowed to stay near the trenches as long as it suited him.

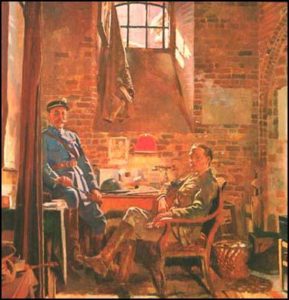

Sir William Orpen. British Staff Officer (1918)

There is no question that his experiences with actual soldiers who were suffering and dying, fighting for their country and his excursions over abandoned battlefields changed any positive preconceptions Orpen might have had of the war and its controversial conduct by Haig. From 1915, 1st Earl Haig had commanded the British Expeditionary Force. It was Haig who ordered the offensive at the Somme, insisting upon repeated offensive attacks on German trenches, ignoring the lack of results–except for more deaths–to the point that he is, to some historians, a very contradictory figure. Today the site of the months long battle, Thiepval Wood, is covered with white crosses, too many of which are marked “unknown.” To understand the reaction of Orpen to the war at its bitter aftermath, it is important to understand the point in time in which the artist arrived at the scene, the Somme, in 1917.

At first the Irish volunteered in great numbers to serve with the British in the war against Germany, but by Christmas of 1914, the war had stalemated and its was clear that what had begun as a plan of blitzkrieg against France had become a war of attrition. By 1916 every soldier understood that the goal was to kill as many of the enemy as possible and to keep on killing the foe until there were no more. Whether one was a soldier fighting for the Entente Cordiale or for the Triple Alliance, that was the plan–simply to kill. In 1914, H. G. Wells had grasped the end game and wrote, The War that Will End War, which began with the passage,

And war is mortal conflict. We have now either to destroy or be destroyed. We have not sought this reckoning, we have done our utmost to avoid it; but now that it has been forced upon us it is imperative that it should be a thorough reckoning. This is a war that touches every man and every home in each of the combatant countries. It is a war, as Mr. Sidney Low has said, not of soldiers but of whole peoples. And it is a war that must be fought to such a finish that every man in each of the nations engaged understands what has happened. There can be no diplomatic settlement that will leave German Imperialism free to explain away its failure to its people and start new preparations. We have to go on until we are absolutely done for, or until the Germans as a people know that they are beaten, and are convinced that they have had enough of war.

A pacifist, Wells had been watching Germany built up its military arsenal and rattle its sabers ever since its victory in the France-Prussian War in 1871. His literary imagination and his close attention to the German mindset made him understand that the only way that war with Germany could be avoided in the future if the nation were first defeated and then disarmed. He wrote optimistically, “This is now a war for peace. It aims straight at disarmament. It aims at a settlement that shall stop this sort of thing for ever. Every soldier who fights against Germany now is a crusader against war. This, the greatest of all wars, is not just another war—it is the last war!” The foot soldier in the trenches, for the airman in his flimsy machine, for the woman nursing the wounded, for the sapper digging beneath no-man’s land, the grim evidence of the clash of mortal and fragile human flesh and impervious modern weapons was all too apparent.

The military strategists lacked both the imagination and the intelligence to understand that the tactics and strategies inherited from the Napoléonic period needed to be changed. Instead of nimble and flexible responses to the new technology, the lines of trenches facing each other from the North Sea to Switzerland mimicked the straight rows of smartly dressed soldiers marching towards each other, firing in unison. Once the smoking muskets were replaced with repeating rifles and machine guns, an advance not fully developed until the Great War, a line of soldiers advancing across open space would be mowed down, scythed like ripe wheat, cut off at the knees. The year 1916 was the year of two horrifying battles, the Battle of Verdun, which lasted almost a year, and adjacent to that killing field, a summer battle broke out at the Somme. Verdun, the site of an old fort, was of importance only in the minds of the French, for that particular fort, dating back to Roman times, had been the last to fall in the Franco-Prussian War. This is a fort that the French would fight for and the German general Wilhelm Falkenhayn deliberately chose this site for his set-piece siege. In any set-piece there is a plan and within the plan of attack there is also a plan of response, predetermined and based upon presumed responses on the part of the enemy. The goal was to attack in force, knock England out of the war, by bleeding France “white.”

The problem with such a plan is that bleeding takes time and as time passed, the German army would also suffer casualties, its own bleeding. The Commander in Chief of the French forces, Joseph Joffre and General Philippe Petain understood the cost to the Germans and, as they had done at the Battle of the Marne, refused to given ground. Petain promised, “Ils ne passeront pas!” and the French assumed their defensive positions. The bleeding began. The French kept alive by their line of supply, a road named Voie Sacrée, celebrated later along with the Petain, the hero of Verdun. Attacking and defending this meaningless salient in the line of trenches cost 163,000 French lives. Entire towns were wiped out, nine martyr villages totally destroyed and never rebuilt, the victims of a German barrage on February 21st. A million shells fired on a single day. The villages were given the status of Mort de France and received the Croix de Guerre. Those who one lived there and, today, their descendants are the citizens of record, one hundred years later. After defending fifty square miles over a period of ten month, the French declared “victory.” But there was no winning and no losing, only pausing, an interlude in what would be a four year war.

Evelyn Anne Woodroffe-Hicks. The Long Road to the Somme (1913)

The British were marked by the Somme as strongly as the French were traumatized by Verdun. On the first of July, fifty eight thousand soldiers were killed, a record for a single day. Unlike Joffre and Petain, the British general Sir Douglas Haig, decided to attack, a dangerous plan in a war where the defense always had the advantage. The idea of taking the initiative was meant to divert the Germans from their positions around Verdun. After pounding the German lines of eight days with an extensive artillery barrage, the British assumed–wrongly–that the soldiers could virtually stroll towards the German trenches where they would find only death. However, the Germans surveyed the preliminary softening attacks quite nicely, thank to bombs that did not explode and concrete bunkers that provide unfailing shelter.

Sir William Orpen. Dead Germans in a Trench (1918)

Perhaps the most successful part the British was the detonation of seventeen mines, announcing that the battle had begun. But the British, laden with supplies intended for the other side, were mowed down, wiping out what was left of a generation. Nothing seemed to make a significant dent in the German lines, not even the new tanks that frightened the Germans but did little damage. The pattern of attacking into the hail of machine gun bullets from the Germans would be repeated for months until it was finally decided that enough bleeding had been done..for the present. In the end, despite minor advances, the lines remained the same and the total British casualties were 420,000 and the French lost an additional 200,000, while the Germans counted half a million men gone, dead, missing, wounded.

Sir William Orpen. German Wire, Thiepval (1917)

The numbers obscure the Irish losses. To this day, it is difficult to count the number of Irish who served and those who died. The basic figures of over 200,00 who fought in the war and of about 50,000 who died, cannot account for the Irish who immigrated to Australia or New Zealand, or even to England. The Irish died at Loos, at Ypres, they died at Gallipoli, and at the Somme. At the Somme and at great cost, only the Ulster Division held its own and took the assigned position on the German line, but, when the other divisions could not advance, the Division had to retreat. Two Ulster Divisions, the 16th and the 26th, were present at Messines Ridge. At the bitter end, a shadow of the Ulster Division was at the last battle of the Somme in 1918. And yet the role of the Irish is not taught in Irish schools, falling in between the cracks of the failure of Home Rule and the rise of Sinn Fein. The Irish artist, William Orpen, for his part, abruptly changed course from a society artist, known for his modern versions of the British swagger portraits, to a horrified accountant, counting causalities of war, both physical and mental. When Orpen arrived at the Somme, the Germans had withdrawn to their fallback position, the Hindenburg Line, but it would take years for the battlefield to fully give up its dead. As Orpen later wrote, he was witness to the harvesting of the ravaged fields:

Never shall I forget my first sight of the Somme in summer-time. I had left it mud, nothing but water, shell-holes and mud – the most gloomy, dreary abomination of desolation the mind could imagine; and now, in the summer of 1917, no words could express the beauty of it. The dreary, dismal mud was baked white and pure – dazzling white. White daisies, red poppies and a blue flower, great masses of them, stretched for miles and miles. The sky a pure dark blue, and the whole air, up to a height of about forty feet, thick with white butterflies: your clothes were covered with butterflies. It was like an enchanted land; but in the place of fairies there were thousands of little white crosses, marked “Unknown British Soldier,” for the most part.

Cooly and unflinchingly, Orpen recorded, in over a hundred acts of reportage, destined for a home audience, what the sons, fathers, brothers and husbands had endured. As his biographer, Bruce Arnold wrote in his 1981 book, Orpen: Mirror to an Age,

He left for France in April 1917, and for the next four years was totally immersed in the war and its aftermath. His output, and its overall excellence, makes him the outstanding war artist of that period, possibly the greatest war artist produced in Britain. Analysis of his war work, the major part of which is in the Imperial War Museum, London, shows a development in style and understanding, from the idealism which inspired him when he first arrived at the front to the disillusionment with the terrible ending to the war, and then the further dismay he and many felt at the direction taken by the peace deliberations. His paintings of the Somme battlefields are haunting recollections of anguish and chaos, of ruined landscapes baked in the summer sun, the torn ground white and rocky, the debris of the dead scattered and ignored.

In 1918, Orpen held an exhibition of the paintings he did on the Front, and, initially, he experienced great success and the acclaimed body of work, over one hundred paintings, watercolors and drawings, were accepted by the public. Even the stark and brightly lite Dead Germans in a Trench was praised. The Times cast a skeptical eye on the painting, noting that the censors would have certainly suppressed a painting of British casualties–as they had done to Christopher Nevinson. The newspaper pondered the work: “Mr Orpen is certainly not a sentimentalist; he seems to paint with cold, serene skill, just as he might paint a bunch of flowers,” wondering if the aim of the censors was to reassure the British public that “only Germans die in this war”

Sir William Orpen. Sir Douglas Haig. Painted at General Headquarters, May 30, 1917 (1918)

Certainly the scenes of death and carnage were softened or should one say, rendered acceptable, by the presence of numerous ‘”khaki paintings” by the artist. These paintings, some of soldiers and many of generals, should be understood as the artist paying his dues to his benefactors, such as Haig, who would later be nicknamed “The Butcher,” for his unwavering dedication to the frontal assault at the Somme and Passchendaele. Apparently Haig had the time to pose for his portrait by Orpen during the campaign. Orpen made himself untouchable in the early years after the war by dint of these portraits of Hugh Trenchard, who would establish and independent air force and became a believer in strategic bombing, Herbert Plumer, who was in charge of Ypres in 1917, Henry Rawlinson, in command at Ypres and the Somme, Henry Wilson, who could not get along with Petain and disapproved for Haig’s strategies, James McCudden, a pilot who won the Victoria Cross only to die on take-off at Auxi le Chateau, Arthur Rhys-Davis, a British pilot, an ace with twenty five victories who disappeared somewhere beyond Roeselare in 1917, Reginald Hoidge, another British ace who shot down important German aces and lived until the early 1960s, John Edward Seely, a Baron, who led the last British calvary charge at the Battle of Morel Wood, and so on, an eclectic collection of hers and villains. One of the (secretly recruited) propagandists for the British government, art critic Arnold Bennett, gave the exhibition official approval:

William Orpen, having discovered a new subject, composes it newly…. Landscape, shell-holes, ruined trees and buildings, dug-outs, tents, and the tragedy and comedy of human existence – he see them as though nobody had ever seen them before; and he arranges them in fresh patterns of contour, colour, plane. His ingenuity in manipulating the material is simply endless, and yet he is never tempted to falsify the material.

This very successful exhibition only enhanced the fame and reputation of Orpen, who was given an important commission. He was invited to Versailles, where the nations who had fought the Great War, the victors and the victims and the defeated alike, gathered together to determine if indeed the conflict had indeed been the War that Will End War. The next post will examine the artist’s answer to the proposition put forward by H.G. Wells four years earlier.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.