Design as Theater, Part One

Designing for Dictators

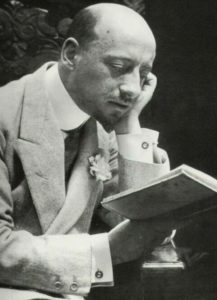

The history of Italian fascism is one of a movement begun in misadventure, characterized by misjudgments and mistakes, ending in farce. If it is defined by any one term, however, that word would be “theatricality.” In his instinctive understanding that the “crowd” loves nothing more than theater and its costumes, Il Duce, Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) provided Italy with an extreme example of how politics becomes aestheticized through the drama of fashion. His erstwhile follower, Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) took note of his strutting but well-dressed role model and re-fashioned his own motley crew of fanatical admirers into a goosestepping nightmare of intimidation. Their mutual point of inspiration was a well-dressed middle-aged Italian poet whose claim to fame was an extreme addiction to sex and fashion. It is not often that one thinks of fascist leaders such as Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler as leading indicators of modern fashion, but fashion design played an important role in what Susan Sontag called the fascination of fascism. Part of the fascination, or to deploy a better word “aesthetics” of fascism, as Sontag pointed out, was the uniform; and the idea that a uniform might be riveting and awe-inspiring was the brainchild of Italy’s famous poet and dandy, Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863-1938). Five foot three inches tall, D’Annunzio was famous fin-de-siècle dandy whose sartorial appetites were as extensive and as adventurous as his many lovers. As much as he loved women, the poet loved clothes so much so that his exquisite wardrobe was featured in a 2010 exhibition at New York University. In the Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò gallery, the exhibition, Gabriele d’Annunzio: Living Life as a Work of Art, showed a wide range of outfits suitable for all occasions, worn by a man considered to be one of the best dressed ever. Six years later, there was another exhibition in Florence, also devoted to his wardrobe and an extensive catalog, Il Guadaroba di Gabriele d’Annunzio, showed an astonishing array of outfits.

According to his biographer, John Woodhouse, the poet or the “warrior bard,” as the Italians referred to him, sunbathed and swam in the nude but when the occasion arose no one was better prepared. As Woodhouse noted, for a simple visit, “D’Annunzio had brought with him a dinner-jacket, six white suits, thirty or forty shirts, and eight pairs of shoes.” It should be noted that he traveled with his own sheets. Colin McDowell noted that the diminutive writer probably used his wardrobe as an instrument of seduction. As the writer noted, his ploy was successful: “Excited by violence and total abandonment, in and out of the bedroom, meant that wherever he was he always had a stream of besotted women at the door waiting to be seduced.” Writing for The New Republic, Jonathan Galassi stated, “Short and physically unprepossessing, some said ugly, he nevertheless possessed an androgynous intensity that was irresistible to many, and had constant affairs, often several at once, throughout his life. D’Annunzio seems to have been an almost involuntary seducer. Today he might be called a sex addict; indeed, there is an aura of needy exhibitionism to much of his behavior.”

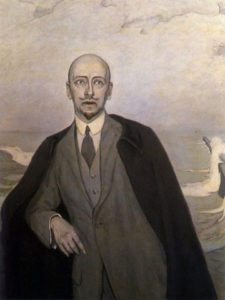

Romaine Brooks. Gabriele D’Annunzio The Poet As Exile (1912)

After serving a single term in the Italian parliament as the “candidate for Beauty,” D’Annunzio was forced to flee to Paris to avoid debt collectors–clothes are very expensive and the poet was a compulsive spender of money, not to mention that his compulsion to acquire made him determined to conquer any woman in his path. As Galassi noted, few could resist him, even a woman who did not like men: “According to the American whiskey heiress and saloniste Natalie Barney: “He was the rage. A woman who had not slept with him made herself ridiculed.” Among his many conquests was the American lesbian artist Romaine Brooks, who painted his portrait.” Clothes, as they say, make the man. When he reached middle age, D’Annunzio was many things–poet, dandy, lover of women, and then the Great War offered him new opportunities. The poet was prescient enough to foresee the military significance of the airplane and he shared with the Futurists a love of war. Yearning for this glory and longing to be a knight of the air like Louis Blériot, D’Annunzio became a fifty-year-old daring pilot who dropped leaflets. The Italians joined the allies two years into the War and perhaps that is why their wishes to “redeem” certain territories in Easter Europe were ignored by those writing the Treaty of Versailles. The background of the desire of Italy to redeem its lost territories must be attributed to the fact that boot-shaped Italy was stuffed with independent republics and independent cities, a legacy from the Medieval and Renaissance period. The Napoléonic Wars had resulted in the further dismemberment of Italian territories, which were given to Austria and France. Even after Italy had become a fully formed nation in the late nineteenth century, bits and pieces where Italian speakers lived were still under the control of hostile nations, including Trentino, Trieste, South Tyrol, parts of Istria, Gorizia, and Dalmatia. Being on the winning side of the Great War would seem to be the ideal time to reunite all the Italian territories into the still young nation. However, from an Italian point of view, justice was not done and the authors of the Treaty summarily turned the port city of Fiume to the new nation, Yugoslavia. The righteous indignation of all those who believed in Italia Irredenta flared up.

In his 1920 book, The Solution of the Fiume Question, D. Dárday wrote of the unhappiness of the “Fiume Italians” struggling under Hungarian rule before the War. Having been pushed to the bottom economically, these unhappy Italians became part of the “Fiume Question” which involved not the Italians or the former Hungarians but the interests of the British Empire. Dárday, writing during the time of the Treaty of Versailles expressed concern that this important coastal port city which was the “key to the Adriatic” should come under the control of “any Mediterranean power.” The author was concerned about the British controlling the “international trade route to the East Indies.” There were two “exits” from the Mediterranean, Gibraltar and the Suez Canal and the power that controlled the city could disrupt British trade. Dárday wrote, “We must therefore regard it as out of the question that Fiume and its sea-board should ever become the possession of that Italy which has a considerable naval power at her disposal; and we regard it as equally out of the question that the Treaty of Peace should afford Yougoslavia (sic) an opportunity, through the possession of Fiume and its sea-board, of developing into an important Slav naval power in the Mediterranean.” As can be seen by this short pamphlet, Fiume was too important to fall into the wrong hands, and yet the territory of Istria once belonged to the Republic of Venice and it seemed that surely the time had come to return the large city to Italy. However, the Italians were not the dominant population group, that would be the Slavs, nor there they the most powerful. The pressing problem was not how to reward Italy but how to give self-determination to the ethnicities of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire. A new nation was formed out of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, and the territory of Istria. As would often happen after the fall of Empires, artificially conjoined peoples would be uncomfortable with their new neighbors. While the unhappiness of the Italians of Fiume is somewhat in doubt, there was no doubt of the anger of the unrewarded Italians.

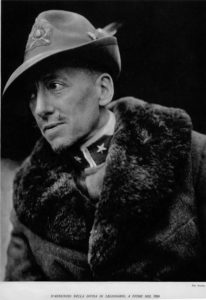

Enter Gabriele d”Annunzio. The poet had enjoyed a very satisfactory war, joining the Italian air force (such as it was), imagining himself a knight of the sky, all the while living in luxury in a palace in Venice. He did pay a price for his bravado, losing an eye in an air raid. The War ended with Italy managing to lose important and humiliating battles while emerging on the winning side and coming away empty-handed. D’Annunzio realized that it was up to him to redeem Italy by reclaiming the long-list territories. His target was Fiume. The new state of Yugoslavia was still too young to fend off even the attack of one-eyed poet and in 1919, D’Annunzio struck. Looking back one hundred years later at what seems a quixotic endeavor, we can see that he serves as a warning to history: never underestimate the power of a celebrity and the ability of people to engage in magical thinking. This magical thinking or the radical imagining of a modern Italy was Janus-faced. On one hand, there was desire, particularly on the part of the Futurists, to shake off the burden of the Italy of the Renaissance, and then, on the other hand, there was a demand to reconnect with the primal energy that formed the Roman Empire. The result was a “myth of national regeneration.” Roger Griffin lists these powerful desires in his book, Modernism and Fascism, including dreams of combining the old and new Italies into “two Italies,” or more simply, the “new Italy,” or the “true Italy,” or the “Great Italy,” or the “Third Italy,” or the “new State,” which would create a “new civilization” for the “new man.” In other words, even before the War exacerbated the grievances of Italy, a strong nationalism emerged. But this nationalism was critical of the old Italy which had proved to be unable to cope with the forces of industrialism and modernism. D’Annunzio had been part of the early twentieth-century discourse on refashioning Italy in terms of modernity, and his literary writings were part of the same impulses that drove the Futurists, led by Filippo Tomasso Marinetti (1876-1944).

Thus from the very beginning, there was a curious union between the avant-garde, literary and artistic, and politics and, in this fevered post-war climate, a poet was the perfect improbable leader. Despite his vaunted status as a poet, D’Annunzio marched off to Fiume in strange company. As in Germany, the streets of Italy were populated by discontented and disillusioned former soldiers, angered by defeat and humiliation, still longing for the good fight they had been promised. Writing in Cabinet in 2015, Renaldo Laddaga described “the assault troops known as the arditi. During the war, the arditi had refused all weapons that would weigh them down: they preferred grenades carried in pockets and daggers held between teeth as they raced toward the enemy trenches, which they rarely reached. They liked to be called “alligators,” were partial to cocaine, and, among them, homosexuality was commonplace. No leader had been able to take for granted the loyalty of these highly volatile men. And now that the war was over, like the German Freikorps, they found no place for themselves in a society where the exhausted majority expected to return to a peaceful civilian life.” The celebrity poet considered which world he would conquer. He thought of marching on Rome itself but decided upon Fiume as being symbolic of all Italy had lost and all that Italy should fight to regain. Gathering his forces, including Marinetti, who was finding Mussolini too conservative for his post-war activist ambitions, D’Annunzio began the Impresa di Fiume or the Endeavor of Fiume on September 12, 1919. There is a sense of opera bouffe–two poets and a couple of thousand ex-soldiers who bit on knives while attacking–but the occupation of Fiume was the opening gun of something that would develop into Fascism. Despite the comic nature of the invasion, the new Soviet Union recognized the Italian Regency of Carnaro.

The citizens of Fiume were excited by such a colorful and energetic occupation and happily accepted the charismatic ruler. Even the Slav population initially enjoyed the experience. The Italian government looked askance upon the inconvenient action of D’Annunzio and refused to accept the “gift” of this city. The allies were not happy with the strange invasion by a notorious poet and the Italian government promised to settle the domestic contretemps and laid siege to the city, waiting for the public euphoria to die down. D’Annunzio had no intention of actually ruling Fiume but found himself in charge, along with a group of avant-gardists who were also unsuited to the practicalities of running a government. For the poet, being in charge meant being on stage. In A History of Fascism, 1914–1945 Stanley G. Payne explained the lasting importance of D’Annunzio’s presence in Fiume. He was, in a very real sense, the personification of the Italian imaginary of the New Italy, which, from the poet’s point of view, had to be manifested through style rather than substance. Perhaps he was driven by his undying obsession with fashion or perhaps he was seized with a new vision of how a new modernist politics could be conducted. One of the most important new books that greatly influenced the political thinking of fin-de-siècle Europe, In 1896 Gustav le Bon wrote The Crowd. A Study of the Popular Mind, in which he noted the breakdown of history and the vacuum that had been left behind. He began his book by saying, “

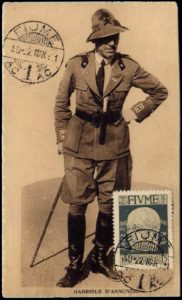

While all our ancient beliefs are tottering and disappearing, while the old pillars of society are giving way one by one, the power of the crowd is the only force that nothing menaces, and of which the prestige is continually on the increase. The age we are about to enter will in truth be the Era of Crowds.” Le Bon wrote with foresight on the subject of the “psychology of crowds:” “The most striking peculiarity presented by a psychological crowd is the following: Whoever be the individuals that compose it, however like or unlike be their mode of life, their occupations, their character, or their intelligence, the fact that they have been transformed into a crowd puts them in possession of a sort of collective mind which makes them feel, think, and act in a manner quite different from that in which each individual of them would feel, think, and act were he in a state of isolation. There are certain ideas and feelings which do not come into being, or do not transform themselves into acts except in the case of individuals forming a crowd. The psychological crowd is a provisional being formed of heterogeneous elements, which for a moment are combined, exactly as the cells which constitute a living body form by their reunion a new being which displays characteristics very different from those possessed by each of the cells singly.” If Gustav Le Bon can be thought of as the predictor of twenty-first-century politics, not to mention, the theorist of the phenomenon that would sweep both Mussolini and Hitler into power, then D’Annunzio could be termed the stylist of political aesthetics. During a time when the last monarchs had just been deposed, he was aware that politics was a form of theater where the common people were involved. It was now impossible to simply decree or dictate; one had to woo, more importantly, one had to excite, one had to sway, one had to enthrall. The crowd would now call the future into being. Of course, there was no one more suited to wooing than Gabriele D’Annunzio, a bald-headed five foot three libertine who had conquered the actors, Eleanor Druze, Sarah Bernhardt and the lesbian Romaine Brooks, not to mention countless other women, including a wife and three children stashed somewhere. As he did when he was courting, D’Annunzio dressed for the occasion, and the occasion was governing an important and strategic port city. As Stanley G. Payne wrote, “..D’Annunzio succeeded in creating a new style of political liturgy made up of elaborate uniforms, special ceremonies, and chants, with speeches from the balcony of city hall to massed audiences in the form of a dialogue with the leader. In other key contributions to what soon became ‘Fascist style,’ D’Annunzio and his followers adopted the artiti’s black shirts as uniform, employed the Roman salute of raising the right arm, developed the mass rallies, brought out the hymn Giovinezza (Youth), organized their armed militia precisely into units, and developed a series of special chants and symbols..” His fashionable troops, clad in black and silver uniforms, were called “The Centurions of Death,” although the black fez was a softening note. A 1921 postcard from Fiume featuring D’Annunzio in his Uniform In order to understand the importance of the proto-fascist fashion statement in modern uniforms, it is important to remember the fate of the military uniform during the Great War. The Austro-Hungarian Empire and the German Empire marched off to war in costumes glittering with absurd epaulets on the shoulders, chests festooned with an array of medals and shiny helmets topped with bobbing plumes. The officer corps, the aristocrats, were installed in the Calvery and rode magnificent horses, and, when not riding, the soldiers advertised their status through the billowing thighs of their trousers. The riding pants narrowed at the knees to allow them to be tucked comfortably in tall glossy leather boots. The counter point to the anachronistic uniforms of the European Empires was the dust-colored khakis of the British military. The British army wore small vestiges of a more colorful past: leather belts and tall boots and a swagger stick, but the uniforms were practical and could be worn in the field without attracting the attention of snipers who could hone in on the glint of a Calvery helmet. D’Annunzio gathered together bits and pieces of past and present and future in the uniform he wore in Fiume. There is a practicality to the basic suit with its long belted jacket with deep and large pockets. The belt holds a long white-handled dagger pointing down to the puffy Clavery pants and the tall riding boots. In a photograph taken in Fiume, D’Annunzio appears in his uniform and we can see that the epaulets are flattened and buttoned down and the chest adornments are played down with black tabs on the collar and details of rank on the lapels and uniform sleeves. The deep cuffs carry the party insignia and the strangely informal hat, a Tyrolean cap, the hat worn by the Alpine Corps, was tilted jauntily on his head. The insignia on the front was accented by a feather slated backward, pinned to the side. Of course, for a man of fashion, this modern uniform was a combination of the past, a bit of nostalgia, a nod to tradition, and the practical present. However, its strong details are definitive and striking. The uniform was an obvious fashion statement, designed to mark the fascists as both political and military forces, stating that ruling would be done with force. The spectators, those who would be controlled, would be impressed by the visuals of the knife and the tall shining boots, hinting of a nearby horse. The crowd had to be evoked and stirred up but the crowd also had to be managed and controlled. As D’Annunzio spoke from his balcony, haranguing the crowd, he trained the masses to be like attentive animals, cocking their heads attentively, waiting for the key words, the familiar phrases, and the rousing chants in order to be stirred as they had been trained to do. As Jonathan Bowden wrote in Counter-Currents Publishing, “..Fiume represented a direct incursion of fantasy into political life because there is a degree to which D’Annunzio combined elements of performance art in his political vocabulary. There’s no doubt that he thought of politics as a form of theater, particularly for the masses, and this is because he was an elitist, because as an elitist he partly despised the masses except as the voluntarist agents of national consciousness. He theatricalized politics in order to give them entertainment without allowing them any particular say in what should be done. This idea of politics as performance art with the masses onstage but as an audience, an audience that responded and yet was not in charge, because there’s nothing democratic about D’Annunzio from his individualistic egotism as an artist all the way through to his sort of quasi-dictatorship of Fiume. He represented a particularly pure synthesis and the violence that was used and so on was largely rhetorical, largely staged, largely a performance, partly a sort of theater piece.” Mussolini would copy this new and strident uniform as soon as D’Annunzio was forced from power, retiring to resume his decadent life of poetry and women. Mussolini would also copy the new title that the poet had given to himself, Il Duce, he would appropriate the artifice of speaking from a balcony, and he would learn from a libertine that politics was entertainment, theater, an exercise in spectacle, an enterprise steeped in aesthetics. If you have found this material useful, please give credit to Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.