The Melancholy Afterlife of Italian Fascist Architecture

Funerary Architecture, Part One

If the population of a nation is alert to warning signs–and usually we are oblivious to portents–it would be well to take notice when that nation begins to build monuments to the glorious dead of the previous war. Disguised as sites of mourning, these are true monuments, not places of mourning, a memorial. For example, in American, there are simple graveyards, known as “veterans’ cemeteries,” a testament to the lack of martial spirit in the New World and to the desire to honor the dead in a simple and dignified manner. But in Italy, after the Great War, the dead soldiers who had fallen for their homeland had to be reinstalled in the national narrative as honorable warriors, not as badly led casualties of an ultimately futile war. Italy had waited cautiously, perhaps wisely, to enter the Great War. Despite the bellicosity of the Futurist artists, Italy was reluctant to fight on the same side as its ancient enemy and fellow member of the Triple Alliance, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and decided to opt instead for a part of the action that would end to their taking a nice bite out of the Empire. Through the Treaty of London in 1915, Britain offered Italy Tyrol, Dalmatia, and Istria, then parts of Austria. Italy was granted its desired control of the borders with Austro-Hungary which stretched from Trentino through the South Tyrol to Trieste. In addition, Britain promised the Albanian port city of Vlore, not to mention Albania, to be taken from the moribund Ottoman Empire. It is very easy to promise that which you cannot deliver, but, for the British, the goal was to activate a southern front and draw the Germans and the Austrians away from the northern front in France and Belgium. The ploy worked well; the Central Powers flooded in: the Austrians were determined to beat back the avaricious Italians and the Germans were anxious to protect its flank. Now all the Italian Army had to do was to win battles with its former allies. The result of accepting the tempting offer in 1915 was a national tragedy for Italy, terrible losses in one of the most completely forgotten fronts of the War, the Italian front, in the most difficult terrain of the War.

The Border between Italy and Austria

Imagine fighting trench warfare, not on a flat plain, but on a vertical incline: that was the obscure “White War.” Aside from the absorbing recent book By Mark Thompson, The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front 1915-1919, one of the best articles on this calamity of Alpine combat appeared in the Smithsonian Magazine in 2016. “An estimated 600,000 Italians and 400,000 Austrians would die on the Italian Front, many of them in a dozen battles along the Isonzo River in the far northeast. But the front zigzagged 400 miles—nearly as long as the Western Front, in France and Belgium—and much of that crossed rugged mountains, where the fighting was like none the world had ever seen or has seen since,” stated author Brian Mockenhaupt. On the one-hundredth anniversary of the Great War, we are experiencing a global warming that is melting the ice and snow along the Italian-Austrian Alpine border and corpses have been uncovered and the entire landscape of tunnels and warfare in the mountains are now accessible. For the inhabitants of the twenty-first century, such sad remains speak of a futile conflict that brought nothing but catastrophe upon the Italians. The corpses, as described by Mochenhaupt, with blond hair and blue eyes still intact in the skull, are victims of misguided bravery for an impossible cause, but for the citizen of the previous century, a mere decade later, these unknown and buried fields of suffering were sites of unrecognized and unrewarded bravery.

Italian Troops in 1918 Pulling Cannon Up the Side of a Mountain

For the Italians, the War could have been an opportunity to take its place as an important force in European politics, not just a backwater where history lived. Unfortunately, the heroism that was dreamed of was bogged down in the White War, where seizing the high ground was literally the name of the game. The Italians lost the advantage to the Austrians and from then on, their fate was probably sealed. The soldiers could just as easily die from avalanches–many deliberated caused by cannon fire—as from snipers lurking in the crevices of the rock face. Thus the only positive news about the Fronte italiano was that the fighting was far less than four years. As Alex Arbuckle described the carnage:

Fighting on the elevated, mountainous terrain posed unique challenges and hazards. Troops often had to scale sheer cliff faces to reach enemy positions. Maintaining supply lines was a constant struggle. The rocky terrain made artillery shells even deadlier. Whereas the soft earth of the Western Front absorbed much of the shrapnel and concussive force of a shell, the brittle rock of the Italian Front shattered into vicious splinters, leading to 70 percent higher casualties per round. With overly confident commanders sending inexperienced soldiers into fruitless massacres, morale on the Italian side plummeted. Pope Benedict XV condemned the war as “horrible carnage that dishonors Europe,” thousands of soldiers deserted and peasants refused conscription orders..The Sixth Battle of the Isonzo in August 1916 resulted in modest Italian gains and slightly buoyed spirits, but was soon followed by more battles of brutal attrition and no winners. Even the smallest gains in territory had to be abandoned when supply lines failed to keep up..On Dec. 13, 1916, 10,000 men were buried by avalanches..In October 1917, exhausted Austro-Hungarian forces were reinforced by German troops and utterly routed the Italians at the Battle of Caporetto, pushing them back with poison gas and Germany’s newly-developed infiltration tactics. The Italians’ retreat was halted as Allied troops and materials came to their aid. When Germany sent its troops back to the Western Front, the Austro-Hungarians found themselves stalemated once again.

Italian Soldiers Fighting in Difficult Conditions

These terrible struggles over a strip of contested border land dragged on until the Hungarian-Austrian Empire collapsed and the War ended. Despite the loss of millions of men, the Italians had done their job. They distracted the enemy and contributed to the final victory. However, as has been pointed out in previous posts, the nation was not rewarded for its efforts and the attitude of the British and the French made it clear that the Italians had not fought bravely enough. The American refusal to allow a new act of colonialism to take place laid the groundwork for the next war. When he came to power, Mussolini, like Hitler after him, was determined to honor the dead and their sacrifices. The resulting memorials fulfilled a variety of functions. First, they put a period to a long and catastrophic sentence, and second the buildings reminded the allies of the worthiness of the Italians who had actually fought very determinedly and daringly, and, of course, third, the memorials reminded the population that dying for one’s country was a noble cause. The last task of these monuments was very important. When Mussolini took over, Italy was consider to be the relaxed tourist destination it had been in the Nineteenth Century. The general European attitude was that Italian culture was in the past, linked to the Roman Empire and to the Renaissance, with the people of Italy, the Italians themselves, being extras on the sets of past glories. Mussolini had installed himself as a contemporary dictator with military and martial roots and forced Italy to become a militaristic modern state. Fascism, at its core, is fueled by the wars of the past and the wars of the future and works best when the nation under its rule is existing in a state of fear and tension, overwhelmed by feelings of danger and dread. It is the role of the dictator to both incite those fears and to promise to protect the people against those very same fears. These “wars” do not have to be military campaigns; a dictator can easily incite hatred of whatever selected “Other” is convenient. But, following the Great War, both Mussolini and then Hitler, recast themselves as authoritarian figures in carefully designed and tailored military outfits promising imminent war. Mussolini, talked about imperial glory but did very little about preparing for the abstract war to come. Hitler, on the other hand, used the coming war as a public works project, employing men as soldiers, firing up military factories, while stimulating the economy. Both Italy and Germany had lost the Great War and both needed to reclaim military honor and glory.

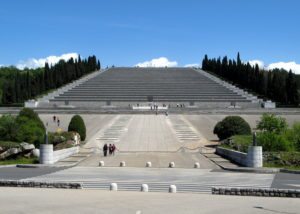

Il Sacrario di Redipuglia

Haunted by the memory of one of Italy’s worst defeats, Caporetto, where the Italian army counted 11,000 dead, 29,000 wounded, 300,000 prisoners and 300,000 scattered men, it was necessary to reestablish Italy as a military power. Until this massive defeat, in which the Germans finally came to the help of the Austrians, the Allies had refused to aid Itay. The Germans and Austrians lost only 50,000 men either killed or wounded and the loss of Caporetto forced the Allies to deliver aid their ally. The fact that this battle was one of twelve battles along the Isonzo River–from modern-day Slovenia to Italian territory–speaks eloquently of the futility of trench warfare. The memorials produced by Italian architects during the interwar were also practical, often being located on the actual battlefields and function as gigantic crypts. During the heat of combat there is little time to collect the dead, and, after the carnage had briefly paused, bodies were buried close to where they fell. There is scant time for nicetities and often identities are lost and many individuals remain unidentified. Famlies waiting fearfully at home never knew how their loved one died or where his body lay. Il Sacrario di Redipuglia, located in Friuli, in the Venezia Giulia area of Italy, is the nation’s official memorial to the war dead. This gigantic ascending ossuary, imagined by the architect, Giovanni Greppi (1884-1960), contained the bodies of over 100,000 Italian dead, over 60,000 of which are unknown. The role of the structure is not just to hold the remains of the soldiers but to also provide the families with a difficult closure and a site to visit–perhaps my son, husband, father, brother is buried here. Greppi worked with the sculptor Giannino Castiglione (1884-1971) to blend the memorial into the rugged landscape as if the site itself had been sculpted out and transformed into a march.

According to Gaetano Dato in his article “Chained Corpses: Warfare, Politics, and Religion After the Hapsburg Empire in the Julian March, 1930s-1970s,” this border area transitioned from a hastily chosen spot for merely collecting and burying the dead to improvised shrines in the 1920s to the final stage of erecting a substantial memorial the purpose of which was to deposit the already gathered remains. The shrine to thirty thousand nameless was established in 1923, but, when he came to power, Mussolini thought the rather homemade homage insufficiently grandiose. The Redipulglia ossuary, built on the original site of the early shrine between 1935 and 1938, was completed just before the Second World War. Going to the site is a pilgrimage to be undertaken reverently, for this is sacred ground, a final resting place. A series of terraces rise up Mont Sei Busi, a high hill overlooking the Redipuglia on the Karst Plateau. The landscape–the territory of the actual battles between the Italians and the Austrians–is not particularly inviting. Flat, marked by scrub, low bushes and twisted trees, an occasional clump of grass, dotted with a brave flower, moving in the wind, the open fields are still cut open by trenches, refuges during a war of attrition. In the spring, the site is quite green and the trees sprout leaves, leavening the bleak harshness of the plain. The hills of the plateau, Sei Busi, San Michele, Calvario, and Sabotino were killing grounds and this Italian gateway into Austria is the site of the memorials of Redipuglia and Oslavia, the Ara Pacis Mundi of Medea, as well as Colle Sant’Elia. But the memorial of Redipuglia is special in its embrace of the visitor. Even though the ossuary is on a plateau, the architect gave the structure a sense of elevation through a series of twenty-two terraces. Although the site is dotted with various and sundry tombs of the generals, such as the Duke of Aosta, the commander of the Third Army, the common soldier is celebrated with the repetition of one word, “presente.” It is as if the dead soldiers hear their names once again, stand to attention, announce their presence, and remind the visitor “we are here.”

According to Hannah Malone in her article, “Fascist Italy’s Ossuaries of the First World War: Objects or Symbols?” “That word refers to the Fascist ritual of the appello or roll call; that is, when an officer called out the name of the dead and his comrades answered presente, meaning that the dead are forever present in the memory of the living and are always ready to serve.” She continued, “However, despite the reiteration of presente, individual histories and memories are notably absent at Redipuglia. The actual identities of the fallen are practically annihilated and the dead are not remembered as husbands, fathers, and sons, but only as soldiers. The annulment of the identities of all but the very highest ranks was elitist, rather than egalitarian, as it underlined the separation of the celebrated, but largely incompetent, commanders from the mass. Their elevation was in line with a Fascist attachment to the principle of hierarchy and to the cult of the leader. Moreover, the narrative that is expressed by Redipuglia obscures the fact that, unlike the hundred thousand soldiers that made up the mass, none of the commanders died in battle, but passed away peacefully in post-war Italy.”

Greppi used the Italian system of perspective in building his receding ascending staircases, presenting the pilgrim with a journey, a series of stations leading to three plain and stark crosses. The staircase or series of terraces act like the horizontal grids of a perspective drawing, drawing the visitor towards a horizon line. As one walks, the horizon line slips back further and the vanishing point leads one onward. Eventually, the climax of the journey is achieved and the vanishing point itself is reached as three crosses crest the straight ridge lines of the levels. The implication is that the fallen soldiers were also fallen martyrs, who are watched over by the Trinity. The three crosses preside over a chapel, which is invisible at the beginning of the journey, and then, at the end, they begin to appear, silhouetted against the sky. Here, behind bronze doors lie trentamila militi ignoti or the remains of thirty thousand unknown soldiers. Although it is far less well-known, Il Sacrario di Redipuglia is, in its scale and impact, comparable to the Douaumont Ossuary, marking the many battles of Verdun and the Thiepval Memorial of the Missing of the Somme. The font used for the memorial is (ancient) Roman, referencing the fact that, as Dato wrote, this Adriatic area was called Venezia Giulia or Julian Venice or the Julian March. From Mussolini’s perspective, the classical assemblage of Redipuglia was meant to rewrite history. Here, like ancient Romans, rest the modern soldiers of the Great War, who would be symbolically mobilized to demonstrate that he, Mussolini, was going to “restore the splendor of the Roman Empire,” as Dato said and continued, “Based on these complex historical events, we can argue that the Adriatic borderland is a place where the Latin, Germanic and Slavic worlds meet and clash..the culture of commemoration in the northern Adriatic region, after the Great War, reflected the change in social and political relationships in European Society: the new role of the masses, a greater acknowledgment of the individual dimension of life, the new concepts of citizenship and universal suffrage and other sociocultural features typical of the new century.”

The site, its significations of pilgrimage and stations of suffering, was far more than a mere graveyard, a repositioning of bones: Il Sacrario di Redipuglia was obviously intended to write a new chapter in the political use of the sacrifice of ill-fated young men. In other words, the ossuary does not look back to the actual battles of the Great War, but beckons forward: be worthy of the sacrifice of these brave men and be prepared to sacrifice once again in the new war coming. Mussolini intended to wipe out the history of defeat and shame and to replace the trauma of loss with the myth of coming imperial glory in the twentieth century. The meaning of the “unknown soldier”–the sad loss of identity of thousands–was replaced by Italian Fascist notions of masses of nameless people following the dictator into war. From the tragedy of having no identity to the loss of identity as being a positive attribute for Fascism. The shrouding of individuals in unwanted uniforms discussed in previous posts is activated once again here with an over-arching theme of generals and soldiers lying together ready to march once more for the glory of the Emperor. It is no accident that it was first D’Annunzio and then Mussolini who revived the ancient Roman salute of the raised and stiff salute, the arm stretching out towards the great leader while signifying, “we who are about to die, salute you.” As Dato pointed out, the meaning of the reactivated myth was blunted by the Italian alliance with Germany, the enemy during the last war. A new generation of Italian men would fight and die to honor these symbolic corpses.

But there is more to say about the interwar construction of funerary architecture under Italian fascism in Part Two.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.