NATURE AS CULTURE: DERRIDA’S TRACE

The Problem with Origins

Following his tour de force presentation of “Structure Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences” in 1967, Jacques Derrida astonishingly published three books: De la Grammatologie. Collection Critique (1967), L’écriture et la différence (1967), and La Voix et le phénomène: Introduction au problème du signe dans la phénoménologie de Husserl (1967). These books were a remarkable outburst of philosophical re-thinking of modern philosophy through a re-reading of foundational texts. Sadly for Americans who did not speak French there was nearly a decade before translation: Speech and Phenomena and Other Essays on Husserl’s Theory of Signs was translated by David B. Allison in 1973. Of Grammatology was translated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak in 1976 and published by the Johns Hopkins University Press, the site where Derrida had made his American debut. Two years later, Writing and Difference was translated by Alan Bass. Perhaps because of the lags in translations and publications, American explicators tend to discuss these seminal reputation-making books in toto, generalizing the content into a discussion of Derrida’s intellectual project. But, that said, this trio of books, consisting a collections of essays, all attack the presence of metaphysics laced through modern philosophy. The relationships among these books posed a problem of even the early readers as translator Alan Bass pointed out,

Derrida first says that De la grammatologie can be considered a bipartite work in the middle of which one could insert L’écriture et la différence. By implication, this would make the first half of De la grammatologie —in which Derrida demonstrates the system of ideas which from ancient to modern times has regulated the notion of the sign—the preface to L’écriture et la différence..The last five essays of L’écriture et la différence, Derrida states, are situated or engaged in “l’ouverture grammatologique,” the grammatological opening. According to Derrida’s statements a bit later in the interview, this “grammatological opening,” whose theoretical matrix is elaborated in the first half of De la grammatologie —which, to restate, systematizes the ideas about the sign, writing and metaphysics which are scattered throughout L’écriture et la différence —can be defined as the “deconstruction” of philosophy by examining in the most faithful, rigorous way the “structured genealogy” of all of philosophy’s concepts; and to do so in order to determine what issues the history of philosophy has hidden, forbidden, or repressed. The first step of this deconstruction of philosophy, which attempts to locate that which is present nowhere in philosophy. i.e., that which philosophy must hide in order to remain philosophy, is precisely the examination of the notion of presence as undertaken by Heidegger.

“Presence,” therefore, precedes everything and permeates philosophy which, as Derrida pointed out, attempts to expel it but, like philosopher Edmund Husserl, always return to lean upon what is essentially a belief system. From a Derridan perspective, this metaphysical system of thought is dependent upon “logos,” language, the word, expressed as the sign. The sign, in turn, was based upon the assumption of the existence of equally metaphysical concepts such as “essence, truth and the foundation of belief” but most importantly a “presence.” The speaker whose immediacy gave authenticity to the word/sign and weight to the signifier. In Of Grammatology, Derrida noted that the idea of “presence” is the desire for something beyond language itself or a transcendental signifier of Logos. Logos implies something beyond any mere speaker; logos implies something far grander that guarantees word: idea, world spirit, God, some point of origin from which speech emerged. The problem for philosophy is that the discipline attempts to erase or eradicate writing, conceived of as “secondary” to speech and gives itself over the the presumption that philosophy is not mere writing but transcends marks on a page. But, Derrida warned, “..the wandering outcast of linguistics has indeed never ceased to haunt language..”

This “haunting” of philosophy by logos needs to be recognized and Derrida’s philosophical project is to re-read and to undermine philosophical texts with the plan of finding internal contradictions embedded in the supposedly perfectly transparent revelation of pure thought (speech). According to Derrida, phonocentricism, or the centering and privileging of the voice (primary, present) over writing (secondary, absent) controls structural linguistics and orders the field of study without being acknowledge. In returning to his duel with Claude Lévi-Strauss, he insisted that the “logocentric epoch” or the “structuralist turn,” is founded upon the concept of a structure which, in turn, depends upon the center or the concept of a center. Furthermore, this Center is (Heidegger) Being or Presence, the ontological ground, the source of origin making certain, reassuming the value of speech. Indeed Logocentrism relates to centrism, or the assumption that the structure has a center. The ultimate center, then, is an authorizing presence, made manifest by the human desire to posit a central presence, logos, in the heart of language and this desire is a longing for a center. Reason, in this case, coils back upon itself. The desire for the center predates the center and once centrality is willed into the structure, the center is outside itself.

With the mind-numbing assertion that the center is not the center, the history of contemporary (or postmodern) deconstruction begins with Jacques Derrida and these three books, De la Grammatologie, l’écriture et la différence, la voix et le phéomène, which in 1967, began with a challenge to both Saussure and Husserl over this fundamental question of presence. Derrida criticized Ferdinand de Saussure for studying only speech rather than that also looking the connection between speech and writing, and in “Structure Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences,” he criticized Lévi-Strauss who also considered the verbal as being primary and originally and presented writing as dependent, implying that writing was a mere technique, a symptom of civilization and the loss of innocence. According to Derrida, these philosophical rejections of writing were signals embedded in the texts of the broader tendency of logocentricism or the nostalgic longing for the divine mind (God), the impossible self-presence of the full self-consciousness of the subject. This self-consciousness is also a fantasy of being able to say what one means, of controlling words and their intent through the fullness of presence or the totality of existence.

Just as Derrida was unwilling to accept existentialism, the romantic philosophy of self par excellence, he also noted that when constructing his philosophy of phenomenology, Edmund Husserl assumed a principle of the voice or the inner soliloquy–the ability to think and speak simultaneously. Most of us expect that when we speak our speech comes from our own personal “psychic interiority” or the depths of the mind cloaked by the speech act. We think that we speak directly and “naturally,” meaning that we assume that speech is spontaneous, compared to writing. When we write we are at a distance, a remove from the fullness of speaking, reproducing mechanically our second-hand unspoken thoughts. Writing, we assume, is a mere transcript of speech, artificial, not authentic, and alienated, rather than connected. But these assumptions and beliefs, which permeate philosophy, are naïve and rest precariously upon an unsustainable belief system. Derrida explained that, contrary to the assumption that logos pre-exists communication and can be traced back to some kind of primordial paradise, language is no pure and has never been pure. Writing has always preceded speech, not the other way around.

The distinction between speech and writing depends upon difference–speech is different from writing and vice versa, just as presence is the opposite of absence. Opposition is fundamental to Structuralism but, as Derrida said, “The living present springs forth out of its nonidentity with itself and from the possibility of a retentional trace. It is already a trace.” Writing invades the assumed ontology of language/linguistics as difference or “trace,” or distinguishing mark. This “living present,” or the trace, which is always present, is the effect of difference, of spacing between terms. Because of the ineradicable trace, according to Derrida, transcendental meaning through speech is a fiction necessary for philosophy. Modern philosophy depended upon such thinking in that the “metaphysical” is a thought system that allows us to think and depends upon the figure or metaphor of a foundation, a ground, a place to put the thoughts to follow. This first principle or starting point is defined by what is excluded by binary opposition.

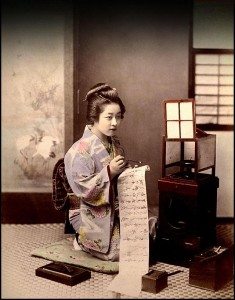

Photograph of Japanese woman writing by Kusakabe Kimbei

As Derrida pointed out in “Structure Sign and Play,” it is necessary to structure these neat oppositions in order to control surplus meaning and indeed Structuralism and its entire edifice was “built” on binaries: signifier/signified, sensible/intelligible, speech/writing, diachrony/synchrony, space/time, passivity/activity–these oppositions are axiomatic but the ultimate point of reference, the prime assumption, is the “presence of a presence.” The idea that the present can be frozen is, of course, a convenient fiction. In addition, Derrida revealed, these binaries, far from being mere organizing principles, are actual ideologies, ways of seeing that give preference toward one term over the other. Logos spawns hierarchized oppositions in terms of a superior term, denoting presence and an inferior term, which is fallen. There is something Biblical about binary oppositions: one term is “innocent” and the other is “fallen.”

Derrida’s insight is indicative of his “origins” as a colonial from Algeria, an colonized person in the heart of French intellectual territory, a Jewish man in a Gentile nation. At the heart of his critique of Lévi-Strauss was his ethnocentrism and imposition of cultural superiority over the “natives” of Brazil. But Lévi-Strauss was hardly along in his flawed thinking: previous philosophers had, since Jean-Jacques Rousseau, used a nature/culture opposition, implying an unfortunate evolution of human beings out of an originary Arcadia after living in an innocent state of nature as speakers. The culture of writing becomes a supplement or an excessive appendage, that both adds and substitutes, that is both detrimental and beneficial. However “beneficial” civilization might be, the first term of the pair, “nature,” is still longed for as a kind of lost innocence, and becomes the privileged entity. For Rousseau, nature is self-sufficient but human beings need culture, the supplement, the impure interloper. But for Derrida, there is no original and an un-supplemented or pure nature is impossible, because humans are present.

We can never know nature and because we are culture our concept of “Nature” is already a supplement because it is we who have “written” or fabricated it. Like Being, Nature escapes our comprehension and yet the concept of necessary in order to speak of culture. Nature must be sous rature, put “under erasure”–we cannot understand nature but we must have it, erased but nevertheless present. In other words, there can be no concept of “nature” without “culture,” and the “nature” is assumed to pre-exist “culture” has no meaning without the existence of “culture.” In realizing that the terms are weighted in preference, in understanding that these weights are ideological, Derrida pushes philosophy out of the Garden of Logos.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.