Discours/Figure (1971)

Part Two: Veduta

In 1971, in the wake of Jacques Derrida’s 1966 presentation Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences at Johns Hopkins University, the Deconstruction of Structuralism was well under way. Jean-François Lyotard proposed the Figural which opens the discourse to heterogeneity (multiplicity) by introducing a difference that cannot be rationalized or subsumed within the rule of representation. Because of its attachment to vision (the eye) the figural cannot be brought under the logic of identity as an opposition to the text. Discourse is not the opposite of the Figure; the Figural is not the opposite of the Discursive. The discursive system cannot deal with the singularity or the disruption of the figure. The Figural is not the figurative but because it is embedded in vision/seeing, the figural is linked to art making. Politically, the Figure is that which rebells against a system (of language) and resists the totalizing effects of the linguistic network, marking the subversion of that which has been repressed. Psychologically, the Figure is the (Freudian) denial of that which is desired through negation. Historically, the Figure is the event, that which disrupts history and interrupts its supposed trajectory. The Figure breaks through the seamless Discourse as a ghost which haunts its conquerer.

Like Theodor Adorno in Negative Dialectics (1969) a few years earlier, Lyotard insisted upon the singularity against totality or “identity thinking.” The figural (the eye) marks this resistance to the text, a coexistence of incommensurable heterogeneous spaces, that of text and the figure. The discursive is actually interwoven with the figural and vice-versa. As Lyotard explained,

Only from within language can one get to and enter the figure. One can get to the figure by making clear that every discourse possesses its counterpart, the object of which it speaks, which is over there, like what it designates in a horizon: sight on the edge of discourse. And one can get in the figure without leaving language behind because the figure is embedded in it. One only has to allow oneself to slip into the well of discourse to find the eye lodged at its core an eye of discourse in the sense that at the center of the cyclone lies an eye of calm. The figure is both without and within.

In 1856 it was Karl Marx who said, “In our days, everything seems pregnant with its contrary” and so it is that the figure is always haunting discourse. In January 2014, mathematician Vlad Ionescu explained,

The figural is exactly that which comes as Unheimlich into language, breaking it into forms (visual and linguistic) that fall short in comprehending. It is not a mere variation on the sharable language but precisely an effect that this language fails to grasp in its own syntax and morphology.

The figural cannot be comprehended and becomes an ungovernable excess or alterity that disrupts the illusion of transparency that drives discourse. The figure “points” away from discourse, calling attention to the unauthorized Other that lies outside the boundaries of text. The act of pointing is referential or indicative of something else, and its function is both paradoxically necessary to and disruptive of signification. Designation is figural and introduces the visible to textual space but immediately seeks to suppress the necessary but disruptive Other. The sensible, i.e. sensory, field is absolutely heterogeneous and impure, and this encounter between textuality and vision (the eye) happens at the edges of discourse, around the periphery. The figural, then, is the Other, rejected by semiotics or phenomenological theory, but returns persistently in the realm of the visual arts, where it is allowed to exist.

For Lyotard, deconstruction is the account of figurality by suggesting a plurality or multiplicity (heterogeneity), not an opposition, as the characteristic of the differential nature of the sign. He introduced an alterity of the visible into the textual space of linguistic signification. In so doing, Lyotard was refuting the rules of discourse which define the space of communication but he is also foregrounding the fact that in order for a purely textual discourse to function, the figural must be repressed. The philosopher locates this repression of the figural by the textual in the history of the visual arts. In an italicized chapter in the middle of Discourse, Figure, “Veduta” Lyotard noted that while Medieval manuscripts allowed text and image to coexist, by the Renaissance the figure was excluded from the text and was given its own and separate field, the visual arts, i.e. painting. The total separation would take time and lingering instances of heterogeneity within works of art, in which two systems of visual communication coexist in unresolved differentiation. In Massacio’s Trinity (1427-8) below, a flat Romanesque armature encases a deep Renaissance space with contains a sculptural body of a crucified Christ.

Trinity (1427-8)

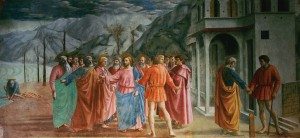

Lyotard understood that Renaissance perspective was a totalizing and constructed system of en-visioning that was totally divorced from actual vision. Like the camera obscure which cut off peripheral vision and thus flattened the curved field created by the human eye/s, the result of perspective was a “cube” that was “closed” as opposed to a curved space which is “open.” The example that Lyotard used in Discourse, Figure was one put forward by Pierre Francastel (1900-1970) who wrote on The Tribute Money (1425) by Masaccio (1401-1428). The Tribute Money below demonstrated a very rare example of an open, not closed, visual space. Technically, the painting is an example of a “continuous narrative,” or a story told across time in three scenes in the same expanded space. This is a Medieval convention carried over into the Early Renaissance. Thus, the “figure” of the tax collector who both initiates the movement through time but who also shifts in time himself, pivoting from center stage to stage right is the Figural that disrupted the Discourse of Renaissance perspective.

The Tribute Money (1425)

Perspective depends upon the fiction of one eye at one point in time immobilized within a net of orthogonal lines meeting at the vanishing point of a horizontal horizon line. The Figural (the tax collector dressed in orange) cannot be contained within this field of representation. Indeed the role of the tax collector functions like the Figure itself–he points, he designates, he references to that which is beyond the peripheral vision of the paralyzed eye and the flattened plotted space of the cube. This gesturing of the over “here” and then the indication of the passing of time which goes over “there” is the deixis, the “pointing outside itself,” as Bill Readings expressed it. But Lyotard had an even more radical example of two heterogeneous “spaces” co-exising, however uneasily, without ever being reconciled to each other.

Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors (1533) was painted one hundred years after Masaccio’s didactic narrative of “the tribute money.” Less a story and more a presentation of the French ambassadors to the court of King Henry VIII, The Ambassadors shows two sharp-dressed men standing in a shallow space, backed by a green brocade curtain. The two fashionable ambassadors, looking older than two men in their twenties, flank, bookend, a set of open shelves crowded with symbols of diplomacy and religious principles and scientific endeavors–in other words, discourse. But oddly, at the bottom of the painting is a distorted skull, an anamorphosis or an object from another system of vision. When viewed by the mobile spectator from a skewed angle, the skull becomes apparent or enters into the space to the right of the center of the centralized perspectival space of the Ambassadors themselves. Regardless of what it may or may not symbolize, the skull, from a Lyotardian point of view, is the Figural, another space, another form of seeing embedded in and disrupting Renaissance space.

Hans Holbein. The Ambassadors (1533)

The Ambassadors indicates that the position of art is a denial of the position of discourse. The skull is the returned of the repressed, the persistence of the negativity that is always present at the heart of the positivity of rationalized space. The position of art indicates a function of the figure, in this case the skull, which is not signified, indicating that this disruptive function haunts the edge of and/or within discourse. The symbols in this painting are transcended by the figure, that is to say, a spatial manifestation of the skull which the linguistic space of the Ambassadors cannot incorporate without being overthrown, an exteriority which cannot be interiorized as a signification, because what the skull “means” is not important. The skull, in a Lyotardian analysis, is art as plasticity, not textuality, art as desire, not discourse, art as a curved extension, not the cube, in the face of totalizing invariance and all consuming reason. The skull is about the eye and its (repressed) desires as explained by Sigmund Freud.

Lyotard used Postmodernism to introduce figurality by suggesting that a figural work of art is to block together motivated and unmotivated language. According to Bill Readings in Introducing Lyotard. Art and Politics, “blocking together” is overprinting or superimposition, an occupation of the same space by two things, while each remaining distinct. This “blocking” is a form of Dream Work–apparently unrelated objects lying adjacent, denying their unspoken meaning. Blocking permits denial of desire through negativity: “this is not my mother,” as Sigmund Freud pointed out means “this is my mother:” Die Verneinung. Linear or Renaissance perspective was understood as a kind of text that produces a fiction of “space” based upon straight lines at the expense of and the exclusion of the Other or curved lines. But Lyotard insisted on the presence of heterogeneity of curved space in vision and insisted on a different kind of seeing at the margin of vision, seen in the veduta of Canaletto’s distorted perspective of a townscape. The denied, Verneinung, asserts itself by its negation and the curved space of the eye’s “savage” vision strains against the cubed boundaries of Canaletto’s frames. The presentation of only one possible construction–the box of the camera obscura–deforms all others compared to a pluralistic presentation of numerous focal points and the viewer can choose among them indifferently.

As in The Tribute Money, Lyotard thought of time figurally, rather than as an ordered sequence of moments and attempted to think time otherwise than by a means of historical discourse with its presumed teleology. He understood the Postmodern as a temporal aproria or a gap in the thinking of time caused by the time of the “event.” Lyotard championed the style of hyperrealism as a temporal freezing, in which a moment–an arbitrary “event” is arrested by the snapshot, disrupting the “flow” of time itself. The figural force of this event/that moment over “there” gestures to and disrupts the possibility of thinking of history as a succession of moments. The postmodern is a rethinking of a culture. The Postmodern is necessarily a figure for the modern discourse.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.