JEAN-LÉON GÉRÔME: History Painter

Part One

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824 – 1904) was on the wrong side of history. Many people have been on the wrong side of history, and, like the segregationist Senator, Strom Thurmond, they deserve to stay there. However, art history is more subjective than history-history, which is supposedly based upon verifiable facts. Art falls into the perilous zone of subjectivity and art and artists are subjected to the rise and fall of critical preferences and of aesthetic judgments. Gérôme was art history’s most vile villain, most reliable enemy to all things Modernist. He was the perfect foil to Édouard Manet (1832-1883), Claude Monet (1840-1926), and Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), not because he was a popular and successful Salon artist but because he railed against his Impressionist counterparts, often and in public, on the record. But since the 1980s, a “younger” generation of art historians, in search of new material for dissertations, began to revive the dead dinosaurs of “official” French art. And Gérôme was among the Salon artists most in need of revision. Without championing Gérôme, it can be said that it is necessary for him to be re-placed in the history of Nineteenth-century art, if only to better understand the Modernist artists and their accomplishments and their courage. It is important to understand the vast differences between Gérôme and the Impressionists in terms of painting techniques and the subject matter in order to comprehend the reception of the art audience and Salon goers.

When the real art history of the Second Empire and the Third Republic in France was restored by the new art historians, it was revealed that Gérôme was genuinely popular with the art audiences and collectors of his time because his art was immensely innovative, decidedly novel, technically proficient (not outstanding but good enough), and, above all, featured sex and violence. A can’t miss combination. The reason why he fell off the art history pantheon was, as all art historians know, because of the Theory of Modernism. Beginning somewhere around the art critic, Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), migrating to the British critic, Roger Fry (1866-1934) and culminating in the American critic, Clement Greenberg (1909-1994), this theory put forward an entity called “Modernism,” both a state of mind and a period of time, that produced an artistic attitude called “art-for-art’s sake,” which led to avant-garde art, a reaction to modernité.

According to the teleology of Modernism, the founding fathers (no mothers allowed) were Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) and Édouard Manet (1832-1883) and their progeny, the Impressionists, the Post-Impressionists and all the “isms” of the twentieth century, climaxing with Jackson Pollock (1912-1956). Any artist, no matter how historically famous and successful, could not be a Modernist unless he (not she: women were not considered) was part of that select group. The artists of the Salon were eliminated, the “official” artists were purged, English and American artists were left out, and only a small group of French male artists were allowed to be part of the club. The result was an art history based upon an evolutionary theory of a progressive march taken by art from representation to abstraction. The Greenberg story of art was an excellent metanarrative, as Jean-François Lyotard (1924-1998) would later call it, but it was not a proper history of art. Modernism was a construct, a convenient fiction, complete with heroes and villains.

The Artist and the Public

Art Historian Gerald Ackerman (1928-), whom I met while I was in graduate school, began the revival of Gérôme’s art if not his reputation. At the time, Ackerman told me he had been working on Gérôme for twenty years and it is his pioneering effort that is the foundation of scholarship for today’s writers. Current scholars point out that, even in his own time, Gérôme was as controversial with the critics as the avant-garde artists. Like the latter, Gérôme had to court and please the bourgeoisie, and the career-minded artist created a juste milieu path between erudite, orthodox, high-minded history painting and low-caste genre scenes of everyday life (“Molière Breakfasting with Louis XIV,” 1862). Taking a page from the playbook employed by Ernst Meissonier (1815-1891), Gérôme rethought history painting and made it accessible and entertaining to the middle class art audience (“The Tulip Folly,” 1862). In place of classical knowledge, understandable to scholars and specialists, the artist inserted carefully researched archaeological and ethnographic detail (“Solomon’s Wall, Jerusalem,” 1876). In place of the relentless ordinariness of Realism and the remorseless observation of Naturalism, Gérôme substituted panoply of information, educating the viewer. Instead of heroes and noble characters, he created a cast for his theater of history and used the actors to tell arresting stories about life in another place and another time.

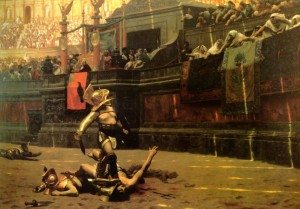

Gérôme’s art presents the viewer spectacle on two levels, echoing the culture of scopophilia and observation of the Other that was the basis of Second Empire power and Third Republic imperialism and the control of men over women. First, Gérôme’s art provided the kind of sheer spectacle that once held sway during the Roman Empire and moved it to the Salon for the delectation of the art public. Bread, circuses, food and entertainment–if you provide the people with these two necessities, they will tolerate any amount of tyranny. Whether or not this conscious policy is smart or despicable depends upon one’s political point of view. To the middle-class French people, survivors of multiple revolutions and uprisings among the disempowered, a firm hand on the wheel may have seemed a good idea. Second, there is no reason to assume that Gérôme was trying to anything more than present interesting subject matter to his audience. There was probably not much sub-text in his work. Indebted to his imperial patrons, Gérôme was a conservative who would be unwilling to offend his collectors. All he asked of the viewer was to look and enjoy. Clearly he had worked out a formula: sex and violence sells; and the exercise of imperialism in the direction of helpless people comforting to a second-class power.

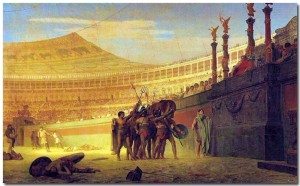

Gérôme’s paintings of the Roman Empire enshrine the pleasure of looking, of seeing violence that happens to others and not to you, a pleasure called by philosopher Edmund Burke (1729-1797), the “sublime.” That heightened and intense emotion that Edmund Burke wrote of was, not incidentally, in relation to the excitement of the French Revolution. For excitement, beheadings notwithstanding, sheer terror and scenes of violence, nothing has out-classed the Roman Empire in its ruthless suppression of any and all acts of dissent or disturbance. No Empire has ever been more blatant in its faithful provision of circuses for its well-fed citizens, even in the provinces. The site of a panoply of horrors was the arena, a word meaning “sand,” which covered the floor in order to absorb the inevitable blood. In the Roman arena, there are no victors, only victims of a system of witnessing what was an imperial display of the Emperor’s power over life and death, preferably death.

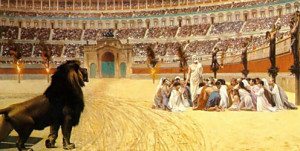

The gladiators, who were slaves, saluted the Emperor before they died in Ave Caesar, Morituri, Te Salutant (1859) and the Christians, who in actuality were prosecuted in very small numbers, provided the fledgling religion with its first martyrs, were favorite characters for the artist. It should be pointed out, that while Christians were expendable, gladiators were not. Expensive to train and to house, the fighters were investments on the part of their owners and it was rare that any of them died in what was usually staged combat. Indeed, Maxime de Camp (1822-1894), photographer of the Middle East, complained that Gérôme was inaccurate, and the artist did, indeed, take liberties for dramatic effect. His painting of Christian martyrs showed human beings used as torches but the scene is set in daytime, while the Emperor Nero put on such a show only at night. In The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayers (1863 – 1883), the lion approaches the huddling worshipers.

Much has been written of Gérôme’s prediction of film and his use of the long pause in a narrative and, indeed, the viewer can see the emerging head of other felines coming into the sand surface of the Coliseum. Like the martyrs, we wait. As opposed to Gathering up the Lions in the Circus (1902), in real life, animals had no interest in attacking humans and had to be taught, even forced to pounce. During these centuries of arena entertainment, wild animals, entire species were either wiped out or put in danger, due to the overindulgence of the Romans who did love their spectacles. The Roman audience in Pollice Verso (1872) came to the arena to be entertained. Some commentators and historians have since suggested that the blood lust acted as a kind of drug, dulling the senses, reducing human carnage to a mere theatrical exercise. There was an endless supply of slaves and criminals to put to death in an exercise of punishment and control.

Although Gérôme could not have imagined modern film, his paintings of the Roman Empire became sources of inspiration for Hollywood film directors, from movie directors C. B. De Mille (1881-1959) to Ridley Scott (1937-). But that observation raises a rather interesting question: why are we still so fascinated with an imperial power, which used human beings as stage lights, crucified even the most insignificant dissidents, rewarded the few and persecuted the many, keeping everything in balance through constant spectacles of blood and violence? Why does Hollywood not make movies about the Greeks, unless they are fighting the Persians in tiny leather uniforms? Do we conclude that we are superior to the Romans in the arena because we are addicted only to movie violence?

In a world where schools have long since sidelined history, most of us learn of the past from the History Channel and Oliver Stone (1946-). Today we could call Gérôme a “popularizer.” If he were a history professor today, he would be complimented for helping the students identify with the events of the past. However, history painting in nineteenth-century France was not necessarily supposed to be popular, only revered and respected. Unlike Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), who dis-respected the Salon system by portraying unattractive uninteresting modern types on a large scale, reserved for history painting, Gérôme kept most of his works small or medium sized. He was, in effect, using the rules to create a new space for what the system had already approved. In the end, he slipped past his many detractors and found fame, fortune, and many honors. As Scott Allan pointed out in his “Introduction” to Reconsidering Gérôme, the artist was “appointed professor at the newly reorganized École des Beaux-Arts in 1863…. (was given) a seat in the Institut de France in 1865…(and was) nominated grand officier of the Legion of Honor in 1898.” Son-in-law to the grand impresario of art reproduction, Adolph Goupil, Gérôme was one of the most reproduced and widely distributed artists of the nineteenth-century. But was he a “good” artist?

The Artist and Technique

Technically speaking, Gérôme was an odd mixture. On one hand, he could handle paint only in a limited manner, for he was essentially a drawer who painted and colored in the lines. On the other hand, he never won the Rome Prize for good reason–he was almost blind when it came to the classical approach to the human figure. Only when he removed himself from the Beaux-Arts tradition did he become at ease with the people he painted. His nude women are borrowed entirely from other artists, especially from Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) and Théodore Chassériau (1819-1856) (Character Study for a Greek Interior, 1850), and are boneless and airbrushed to a peculiar blank flatness. But when Gérôme clothed his females, he was completely at ease. His portrait of the daughter of Betty de Rothschild, who was painted by Ingres in 1848, Portrait of Madame la Baronne Nathaniel de Rothschild (1866) is not as stunning as an Ingres portrait, but Gérôme held his own with the master. His Portrait of M. Édouard Delessert (1864) with the subject nattily dressed in blue argyle socks is a genuine character study.

Gérôme. Portrait of Madame la Baronne Nathaniel de Rothschild (1866)

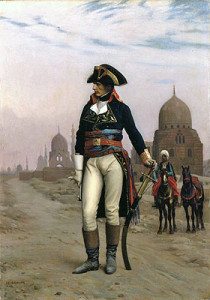

Despite these near-great portraits, Gérôme seemed to have had a hard time integrating actual sites with imaginary people. For example, there is a wonderful trio, featuring Napoléon in Egypt. Napoléon and his General Staff in Egypt (1867) imagines a very large General on a very dainty camel, but it is not the size disparity, it is the startled expression on Napoléon’s face that makes today’s viewer smile. Oedipus (1863 – 86) also plays havoc with scale: Napoléon is on a tiny horse, standing in front of a shrunken Sphinx. But most interesting is Napoléon in Cairo (1867 – 68), a simple little painting with the General standing in full uniform with Islamic mosques in the background. In real life, Napoléon was short and rounded, but here he is tall and slim. The viewer is given a level of information that Meissonier would envy–the details of the uniform are exquisitely rendered and one learns, thanks to the deep shadows of selective folds of his trousers, that the future Emperor “dressed” left. There are probably several reasons for the disparity of scale and proportion in Gérôme’s paintings. One would certainly be his academic training, which taught students to think in pastiche and collage and to “paste,” as it were, standard studio poses into grand backgrounds. Another cause would have been the artist’s use of photography as his source. Photography tended to make minute details available to the human eye, and when Gérôme copied these details, the effect was to flatten the surface with non-hierarchal information that overwhelmed the displaced figures and threw off the scale.

Gérôme emerged onto the Parisian art scene as the leader of the “Neo-Grec” school (according to the critics of his day) with The Cock Fight in the Salon of 1847. The genre painting tells a story of cocks, both seen and unseen, as a young boy orchestrates a contest between two roosters while a young girl shrinks away, as well she might. However, Gérôme did not confine himself to antiquity and the choice of his subjects says a great deal about what was going on in France during his career. Just as his mentor Paul Delaroche (1797-1856) spoke obliquely about the French Revolution (matricide and patricide) with The Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833), Gérôme saluted the Second Empire by celebrating the current Emperor’s uncle, Napoléon I, in a number of paintings, some direct references, some indirect. The rather marvelous The Reception of the Siamese Ambassadors at Fountainebleau (1864) was a direct steal of Jacques-Louis David’s The Coronation of Napoléon (1807). Two other wonderful paintings, The Grey Cardinal (1873) and the Reception of the Duc de Condé at Versailles (1878) were painted after the fall of the Second Empire and could be interpreted as a warning against secret power (the Cardinal and by extension the late Empire) and a plea for reconciliation (Duc de Condé) after rebellion, but, given the inherent political and painterly conservatism of Gérôme, the works could be more comfortably read in relation to the nostalgic Bonapartism and a desire for a monarchy, which marked the unsteady early decades of the ill-fated Third Republic.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.