JEAN-LÉON GÉRÔME: History Painter

Part Three

The Artist and History

Gérôme studied under the official juste milieu artist, Paul Delaroche (1797-1856), who knew how to please a crowd. He had a gift that Gérôme did not: Delaroche could move an audience with his spell binding and compelling scenes of arrested pathos. In The Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833), the blindfolded teenager, England’s nine day queen, gropes for the wooden block where she will lay her little white neck. Dressed in white to emphasize her youth and innocence, the little girl who has been a pawn of reckless and ambitious adults is a triangle of pity in the center. She is flanked by the axe man, the executioner. By his side is his axe, the head of which gleams in anticipation. In Delaroche’s Princes in the Tower, also known as The Children of Edward (1831), the beautiful young princes cower in the dark alerted to approaching danger by a shaft of light under the closed door to their room. The minions of their evil uncle, Richard the III, are upon them. It was this master of the breathless moment who said when photography was invented, “From today, painting is dead!” It was this painter who trained some of the greatest photographers of the new era, men who transformed photography into an art form, Charles Nègre (1820-1880) and Henri Le Secq (1818-1882). But their photographs were doomed to be neglected and unstudied until the Twentieth century. It was another painter, his pupil, Gérôme, who would profit the most from photography.

Although Gérôme benefitted a great deal from his relationship with Goupil & Cie, the art firm he married into and which sold his art, there were many critics in his own time who were wary of the sale of reproduced paintings-as-photographs or as prints. Presaging Walter Benjamin’s (1892-1940) observation that when art is reproduced, it loses its aura, its untouchability, its place in ritual, its role in cult, nineteenth century critics wondered if Gérôme were cheapening himself and his art. But being under contract with the firm, the artist had little control over the fate of his images. Goupil’s did well for the artist, finding for him an audience of buyers for all levels of his works, from the original paintings to different kinds of reproductions, suitable to a wide range of incomes. Most of the buyers for Gérôme were Americans in New York. New Yorkers, especially in the gilded age, loved the opulent visual excess of Gérôme and equated him with all things French. The American buyers tended to not quite understand the distinctions among French artists, and they would purchase an Impressionist painting from Pierre Renoir (1841-1919) and a slick Salon work from William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905) and an Orientalist pastiche by Gérôme, ignorant of theoretical debates in Paris, and show them all together in a way that was historically accurate. After all, these artists were contemporaries.

That said, Gérôme was in the thick of the quarrel between tradition and modernity. The artist who gained the most from technology was the most hostile to artists who dared to think or paint differently. “Rodin, Pissarro, Monet, Degas are rotten scoundrels,” he exclaimed. Famously, Gérôme objected to, among other things, a posthumous exhibition of the art of Édouard Manet (1832-1883) at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1884. The artist derided the recently deceased Manet as “…the apostle of a decadent manner, of a piecemeal art..” Manet, he continued, without a trace of self-consciousness, produced “..highly willful and lurid work..” Of the donation by Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894) of the Impressionist paintings to the Louvre, Gérôme raged, “I repeat, if the State has accepted such rubbish, then moral fiber has seriously withered.” This, from the master of the bared bottom. Invective, no matter how heart-felt or mainstream at the time, seldom passes the test of time. Ernst Meissonier’s (1815-1891) prosecution of Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) after the Commune soured his place in history, and, like Gérôme, who had nothing but spleen for dead artists, the rancor of these popular artists lost them respect from their peers and from history.

The Sculpture

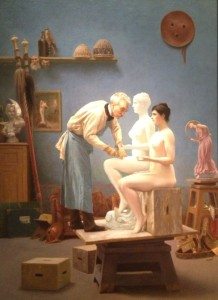

Gérôme did a number of paintings on the theme of the male sculptor and his female model, reflections on the Pygmalion and Galatea myth in which the sculptor created a woman so perfect, he prayed to the gods, asking for her to come alive. From Pygmalion and Galatea (1890), where Galatea comes to life when the delighted Pygmalion kisses her to the tiny The Artist’s Model (1895), when Gérôme becomes Pygmalion, we can trace the desire of Gérôme to make the perfect woman.

Gérôme. The Artist’s Model (1895)

Strangely enough, his women come alive only when they are sculpted, usually larger than life. Polychromed nineteenth century sculpture, especially sculptures with teeth (The Ball Player, 1902) and jewelry are an acquired taste, even for people educated by Jeff Koons. For us today, Gérôme’s The Gladiators (1878) are both reminiscent of fascistic works and of fantasy figures from World of Warcraft. As Édouard Papet pointed out the fact that the ancients polychromed their sculpture had just come to light, when Gérôme was making his sculptures. Accustomed to the bleached whiteness of marble exposed to the elements or buried underground, Europeans must have found it difficult to adjust their taste to the multiple colors of marble used by Charles Henri Joseph Cordier (1827-1905). By the time of Gérôme, his chastely colored females would have been acceptable. But to Modernist educated contemporary viewers, Gérôme’s sculptures were simply gaudy bad taste and they disappeared from view until recently.

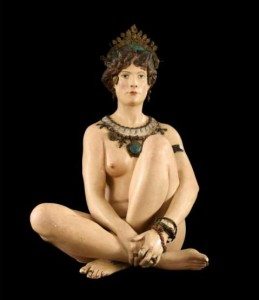

Gérôme. Corinthe (1904)

Of all of the artist’s late sculptural work, the highlight has to be Corinthe (1904). Decked out with jewelry, which is applied to her naked body in every conceivable site, she would be the envy of Jeff Koons; she was the epitome of vulgarity and excess, a siren of the Gilded Age. Corinthe and the portrait of Sarah Bernhardt (1901) were true highpoints of his sculptural career. Paradoxically, the rare paintings by Gérôme, which allow the woman any agency at all, feature the art of sculpture, the craft of Pygmalion. In Painting Breathes Life into Sculpture (1893), a young woman, working in the back of a Tanagra shop, is painting the small female sculptures and is the agent of creation. In ancient Greece, there were women who were allowed to participate in their family’s workshop, but, although they were accomplished artists, they did not sign their names. In The End of the Séance (1886) the still-nude model covers the clay repliant of herself, as though to grant the inanimate object some protection and modesty that she herself has been denied.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.