Arcadia Electrified

John Pfahl at Niagara Falls

In 1881, the artist George Inness, famous for the Lackawanna Valley painting of a train uncoiling from a roundhouse and making its way into the frontiers of Pennsylvania, visited a more natural site, or so he assumed. When he saw Niagara Falls, the artist was overwhelmed by the sublime beauty of water tumbling unchecked over a cliff face. According to the Smithsonian Museum, “Determined to take the “impression of the falls down right away,” but having arrived without painting materials, Inness rushed to the nearby Buffalo, New York studio of an old friend to acquire supplies. At the same time, Inness was creating a series of paintings based on Niagara Falls, the location was undergoing a radical energy transformation brought on by the continued developments of the Industrial Revolution. The Niagara Falls Power Company and numerous partners were working to harness the power of the falls to bring the first hydro-electric power plant to Niagara. Yet, as physical changes brought on by industrial development and shifts in ideas about nature and preservation began to change, so too did the manner in which the falls were viewed and depicted by artists.”

George Inness at Niagara Falls in 1884

However, at the end of the nineteenth century and in the midst of the Industrial Revolution, Inness arrived too late. Niagara Falls had long since been recognized as an important source of power. As the Smithsonian stated, “Since the beginning of the nineteenth century, landowners and entrepreneurs had been busy developing flashy amusements, hotels, and facilities for tourists, as well as constructing large mills and factories – all of which encroached upon the riverbanks of the Falls. In Inness’ Niagara, the billowing smokestack in the background of the painting belongs to a paper mill constructed in the middle of the Niagara River on Bath Island (now Green Island).” In fact, Nikola Tesla said that there was enough power generated by Niagara to “light every lamp, drive every railroad, propel every ship, heat every store, and produce every article manufactured by machinery in the United States.” Tesla attended the opening of a huge hydroelectric power plant at the Falls in 1895 and gave an address at the opening ceremony: “We have many a monument of past ages; we have the palaces and pyramids, the temples of the Greek and the cathedrals of Christendom. In them is exemplified the power of men, the greatness of nations, the love of art and religious devotion. But the monument at Niagara has something of its own, more in accord with our present thoughts and tendencies. It is a monument worthy of our scientific age, a true monument of enlightenment and of peace. It signifies the subjugation of natural forces to the service of man, the discontinuance of barbarous methods, the relieving of millions from want and suffering.”

George Inness. Niagara Falls (1885)

Given the great promise of the Falls and in the face of the nation’s great need for the possibilities that industrialization could unlock, it would seem selfish and short-sighted to not make use of this great natural wonder. But, once taken advantage of, the Falls and the River’s banks would become what the photographer, John Pfahl called an “altered landscape.” Today, we might also define it as a sacrifice zone, akin to those of the West. Although the area of the Niagara Falls has not been poisoned and polluted as the desert lands, it is still undeniably spoiled as a natural wonder. What is left of Niagara Falls, now greatly changed by the demands of modern life, is largely due to efforts to conserve what could be salvaged of its beauty, efforts that date back to the mid-nineteenth century? It is in the midst of the ongoing controversies about the preservation of Niagara Falls versus the exploitation of its resources that George Inness painted Niagara Falls. Although Inness did his best to obliterate or ignore the visible impact of industrialization, his was a vista very different from that seen by John Vanderlyn, a young artist who visited the Canadian side of the Falls on the recommendation of Aaron Burr. Burr had visited the Falls with his daughter and Vanderlyn was looking for the kind of art that would make his name and make some sales along the way.

According to the Albany Institute of History and Art, “The journey from Kingston, New York, to Niagara Falls was an arduous undertaking in 1801, the year artist John Vanderlyn first visited the great cataract..After completing A Distant View of the Falls of Niagara, Vanderlyn sent the painting to Burr for his inspection. Burr in turn showed the painting to the British chargé d’affaires to the United States, Edward Thornton, who had seen the falls himself. Thornton wrote, ‘Mr. Van Der Lyn’s picture contains incomparably the most faithful animated Representation of the falls I have ever seen, it is not for me to judge any of its merits except that of its Perfect Correctness.’”

John Vanderlyn. A Distant View of the Falls of Niagara (1803)

Some one hundred eighty years after Vanderlyn and a hundred years after Inness, John Pfahl (1939-) photographed the banks of the Niagara River, a river which in the 1980s was lined with a huge grid of electrical towers. And yet in his book, Arcadia Revisited. Niagara River and Falls from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario (1988), the photographer could look in another direction and view the preservation of the Falls, to the extent it has been possible, begun through the efforts of Frederic Church and Frederick Law Olmsted. In fact, according to the Burchfield Penny Art Center, Pfahl had been “commissioned by the Amos W. Sangster Niagara River Centennial Committee to celebrate Sangster’s landmark folios of 153 etchings, Niagara River and Falls from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario, published 1886-88. Pfahl revisited many of same sites that Sangster depicted in order to produce awe-inspiring twentieth-century images that also reflect nineteenth-century concepts of the picturesque.” As has been stated in earlier posts, the views of the Niagara Falls would be more properly categorized as “sublime,” if one is thinking in terms of eighteenth-century binaries. In Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Inquiry Into The Origin Of Our Ideas Of The Sublime And Beautiful, the sublime landscape is positioned against the Beautiful. As Burke said, “It is my design to consider beauty as distinguished from the sublime..” This treatise by Burke is as much a psychological document as a philosophical statement. He is one of the earlier writers, who, like Emmanuel Kant, understood that there is a realm poised between reason and irrationality, and that aspect of human nature is called feelings. This is the zone of Kant’s Critique of Judgment and the task of Burke in England and Kant in Germany is to account for feelings by analyzing every element of emotion. Once Burke called out specific aspects of human responses to stimuli, the carefully listed and categorized them, broadly placing the among the umbrellas of pleasure and pain. Pain is the strongest emotion and it is here that we find the sublime. Burke wrote, “Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling. I say the strongest emotion, because I am satisfied the ideas of pain are much more powerful than those which enter on the part of pleasure.”

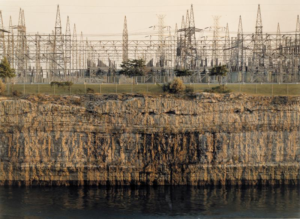

John Pfahl. Niagara Power Project, Niagara Falls, New York (1981)

Frederick Law Olmsted most surely felt anger at the sight of tourists swarming like “locusts” over the natural landscape of Niagara and he and Frederic Church succeeded in having a law passed in 1883 to built a park for the Falls. In the book, Sacred Places: American Tourist Attractions in the Nineteenth Century, John F. Sears made an interesting point. “But it was not merely the means by which the proprietors marketed the sensational aspects of Niagara to which Olmsted objected. He rejected all forms of ‘astonishment,’ including the sublime, out of which he clearly felt that sensationalizing of the Falls had sprung. His approach to Niagara depended not on the categories of the picturesque and the beautiful, which were not applied to grand national phenomena as frequently as the sublime, but were just as well established and derived from the same body of eighteenth-century English aesthetic theory. For Olmsted, the true enjoyment of the Falls required a quiet and pensive contemplation of their beauty. HIs firm rejection of the sublime represented an important turning point in the history of the Falls, although his response to the quieter attractions of Niagara had many precedents..”

John Pfahl. City of Niagara Falls, New York (1985)

Although the word “Arcadia” has been evoked in relation to the work of John Pfahl along the banks of the Niagara River, it is difficult to find satisfying material on Arcadia in contemporary literature. The best book on the subject, incorporating ancient sources and landscape painting and landscape architecture is by Allan R. Ruff. In Arcadian Visions. Pastoral Influence on Poetry, Painting, and the Design of Landscape, he wrote of the significance of Virgil’s Eclogues and considered the importance of ambiguity. Virgil used allegory to oscillate between contemporary political issues of his time in Rome and the evocation of a by-gone time from which we have declined. As he wrote, “The pastoral form is established as a vehicle through which contemporary moral and political issues might be explored without criticism. In essence, the pastoral form presents the reader with a contrast between the idyllic harmony of an alternative world, in which man lives in harmony with nature, and the reality which threatens to destroy it. This is the continuing fascination of the pastoral which has afforded generations of translators, as well writers of their own pastorals and artists of many kinds, the opportunity to use the same ambiguity to comment on society and the issues of the day, whilst hiding behind the guise of a simple pastoral poem.”

Francis R. Kowsky on the Niagara Reservation

It is possible, then, to interpret Pfahl’s trip down the river, following in the footsteps of many processors as a form of allegory. The photographer took a visual journey to a place that had once been untouched, pastoral, pre-urban, as it were, and photographed the cost of “progress,” without putting forward a strong political statement. To “revisit” “Arcadia,” where ever it might have been in America, is to make a comment if only to suggest a contrast between what once was and what exists today. In discussing waterfalls, the photographer said, “Waterfalls in the United States tend to fall into one of two categories. They are either great sources of industrial power or conveyors of aesthetic power and beauty. Most of the waterfalls in the eastern half of the country have been heavily used and abused by humankind. Paper mills, electric plants, and other signs of industrialization frequently have co-opted these views.”

John Pfahl. Horseshoe Falls From Below (September 1985)

John Pfahl. Horseshoe Falls From Below (September 1985)

The other excellent source for understanding the role America plays in the contemporary concept of “Arcadia,” is Leo Marx’s The Machine in the Garden. In fact, he opens his book by conjuring up the pastoral ideal and how it fed the American dream. “The pastoral ideal has been used to define the meaning of America ever since the age of discovery, and it has not yet lost its hold upon the native imagination. The reason is clear enough. The ruling motive of the good shepherd, leading figure of the classic, Virgilian mode, was to withdraw from the great world and begin a new life in a fresh, green landscape. And now here was a virgin continent! Inevitably the European mind was dazzled by the prospect. With an unspoiled hemisphere in view, it seemed that mankind actually might realize what had been thought a poetic fantasy. Soon the dream of a retreat to an oasis of harmony and joy was removed from its traditional literary context. It was embodied in various utopian schemes for making America the site of a new beginning for Western society. In both forms — one literary and the other in essence political — the ideal has figured in the American view of life..” Therefore, it is the ancient ideal of Arcadia and the more modern idea that America was the new Arcadia, against which we measure our environment today.

John Pfahl. Electric Plant from Beaver Island (October 1985)

It is interesting to note that Olmsted’s attempts to return Niagara into some parklike version of Arcadia did not take industrialization into account. The landscape architect’s chief concern was the commercialization brought on by tourism and the resulting clutter that offended his rather patrician soul. As Sears pointed out, “By the 1860s and 1870s, the commercial version of Niagara as a spectacle had threatened to swallow every other experience of the Falls. Olmsted’s plan for the reservation made room for the genteel tourist but defined the proper experience of the Falls as picturesque contemplation rather than sublime excitement..Thus Olmsted provided an alternative mode in which tourists could consume the Falls as a cultural product. But he didn’t defeat the sensational version of the Falls that continued to operate from the periphery of the Niagara Reservation. The two versions of the Falls settled down side by side to vie for the attention of visitors.” As Sears later pointed out, at the turn of the century, there was very little concern from the general public about encroaching industrialization, even upon a place as “sacred” as Niagara Falls.

John Pfahl. Horseshoe Falls With Spring Ice (April 1985)

However, the Falls had always had a role other than as a scenic wonder. The history of the attempts to harness the power of the River and the Falls begins with the arrival of the Industrial Revolution. As the report for the Niagara Falls Historic Preservation Commission stated, “The history of harnessing the flow of the Niagara River at Niagara Falls for manufacturing can be said to have begun when the area was part of New France. In the 1750s, Daniel Joncaire, the French portage master at the Falls, took upon himself to divert river water above the Upper Rapids into a short millrace to turn the wheel of a sawmill. Successive British and early American residents sporadically added to Joncaire’s undertaking.” As Francis R. Kowsky and Martin Wachadlo reported, “By the late nineteenth century, an undistinguished assortment of mills had grown up along the mainland, as the American bank of the river was known, and on Bath Island (the present Green Island) in the American Rapids. A shallow canal that had been built parallel to the river from the Upper Rapids to Prospect Point was home to a number of middling enterprises, including a laundry, a furniture factory, paper mill, planning mills, a foundry, and a hotel.” The authors discussed Olmsted’s attempts to save Niagara by building a Reservation or Park-like preserve by mentioning the “establishment of the Niagara Reservation in 1885 and the subsequent efforts to return the mainland to something like its pre-settlement, natural appearance. Nonetheless, the advent of this ancient form of power involving the diversion of flowing water into races to turn mill wheels and other devices initiated the transformation of the area around the Falls from untouched wilderness to one of the planet’s most extensive industrial addresses.”

John Pfahl. Lower Genesee Falls, New York (October 1989)

In a related series on Waterfalls, John Pfahl trekked to the system of gorges and waterfalls that configure upstate New York. In writing of his photographic decisions, he stated, “Waterfalls photographed close-up and isolated all look very much the same. I chose a panoramic format and wide-angle lenses to provide context and to complicate the meaning and formal qualities of the images.” Once again, Pfahl distanced himself from politics and situated his work in the task at hand: measuring the uses of waterfalls in the East. Here, the story of Niagara was repeated: the surge of tourists who wanted to experience nature, supposedly untamed, and the harnessing of Nature for the purpose of producing power for American industry. Niagara and the adjacent waterfalls make light bulbs turn on, machines hum, and generators to throb. Ironically, in the early twenty-first century, this kind of power–water power–is recognized as a safe clean form of energy, along with solar and wind power. Water power is also one of the most venerable forms of using the land productively, going back to primitive medieval manufacture along the banks of streams and progressing to windmills in Holland and moving to the banks of the Niagara River.

John Pfahl. Niagara Falls, Niagara River, New York (November 1991)