Arcadia as a Metanarrative

The Precursors of John Pfahl

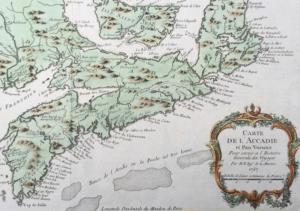

Ever since the historical Arcadia had been lost, swallowed up by the Roman Empire of Augustus, its memory has been mourned and a new Arcadia has been sought. Handed down from Virgil and from the known histories of the classical world, the Bronze Age society, the site of origin for Greek mythology, Arcadia had fired the imaginations of sixteenth-century European explorers. For centuries, they chased various legends to the Americans, from the Fountain of Youth to El Dorado, and, of course, Arcadia. One of the earliest Arcadias in the New World was established in Canada. The Historic Canada website set out the earliest “namings” by the early mapmakers. Acadia has its origins in the explorations of Giovanni da Verrazzano, an Italian explorer serving the king of France. In 1524-25 he explored the Atlantic coast of North America and gave the name “Archadia”, or “Arcadia” in Italian, to a region near the present-day American state of Delaware. In 1566, the cartographer Bolongnini Zaltieri gave a similar name, “Larcadia,” to an area far to the northeast that was to become Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. The 1524 notes of Portuguese explorer Estêvão Gomes also included Newfoundland as part of the area he called “Arcadie.”

Map of Arcadia in Nova Scotia by Nicolas Bellin in 1757

The Nova Scotia colony of Arcadia was founded in the seventeenth century and became embroiled in the militant warfare between the French and the British over which power should control Canada. Fleeing the conflict, small groups of colonists re-settled in Beaubassin, Grand-Pré, and Port-Royal. In these borderlands, the Arcadian people flourished, and, according to the historians: “These highly self-reliant Acadians farmed and raised livestock on marshlands drained by a technique of tide-adaptable barriers called aboiteaux, making dikeland agriculture possible. They hunted, fished and trapped as well; they even had commercial ties with the English colonists in America, usually against the wishes of the French authorities. Acadians considered themselves “neutrals” since Acadia had been transferred a few times between the French and the English. By not taking sides, they hoped to avoid military backlash.”

However, after the early eighteenth century War of Spanish Succession, the colony was ceded to the British, who left the colonists alone. During this period, the Arcadians had the option to move into French territories but, given that the British presence was heavy-handed but limited, the neutral colonists stayed behind and flourished during a Golden Age. By mid-century, the British took an active military role in Nova Scotia, demanding allegiance from the Arcadians, an oath they were reluctant to make. Their early independence, their self-identification as “Arcadians,” rather than as subjects of either the French or British crown, presaged the position of the American colonists in near-by New York. Reluctant to deal with a dissident population in a still-disputed territory, the British summarily proceeded to deport the Arcadians, a process that dragged out from 1755 to 1762, coinciding with the Seven Years War.

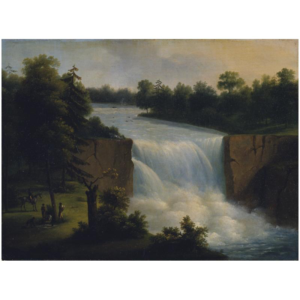

The first view of Niagara Falls by Captain Thomas Davies (1762)

In the midst of this war, a certain Captian Thomas Davies drew a rather fanciful view of Niagara Falls, determined to be one of the first renditions of this now famous site. According to Christie’s specialist, Nicholas Lambourn, there had been narrative accounts of the Falls for the past century but no pictorial interpretation. According to Lambourn, “The first depictions of the Falls were wildly inaccurate. What is particularly interesting about this work is that Davies was not only painting on the spot, but was a military surveyor — he was trained to show things accurately. This is not a fantastic or romantic work, but a scientific document.” In fact beneath the watercolor is an inscription “The Perpendicular height of the Fall 162 feet.” Lanbourn continued, “The falls were deep in what was called Indian Territory,” which accounts for the presence of the Native Americans in the picture. The rainbow, a common phenomenon when light touches misting water had a different meaning: “In the 18th century a rainbow signified the divinely instituted covenant established between man and God after the Flood. Captain Thomas Davies has envisaged a ‘Peaceable Kingdom’ in the very midst of the Seven Years’ War, adding a deeply poetic dimension to a topographical drawing.”

According to Canadian historians: “The deportation process once instigated, lasted from 1755 to 1762. The settlers were put into ships and deported to English colonies along the eastern seaboard as far south as Georgia. Others managed to flee to French territory or to hide in the woods. It is estimated that three-quarters of the Acadian population were deported; the rest avoided this fate through flight. An unknown number of Acadians perished from hunger or disease; a few ships full of exiles sank on the high seas with their human cargo.” Arcadia was lost again, but those who remained behind in Canada would become part of the remaining French Catholic presence in southeastern Canada. During the nineteenth century, they struggled to retain their unique identity and preserve their heritage. It was during this time of identity politics and nostalgic memory that the “Arcadians” lost, scattered and dispersed and yet still vital were celebrated in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s famous poem, Evangeline (1847). Out of fashion now, this very long epic was a love story folded into a sad tale of deportation that became a story of the settlement of frontier lands in America by the displaced Arcadians. The poem was best known through its opening stanzas:

This is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and hemlocks,

Bearded with moss, and in garments green, indistinct in the twilight,

Stand like Druids of eld, with voices sad and prophetic,

Stand like harpers hoar, with beards that rest on their bosoms

Loud from its rocky caverns, the deep-voiced neighboring ocean

Speaks, and in accents disconsolate answers the wail of the forest.

This is the forest primeval; but where are the hearts that beneath it

Leaped like the roe, when he hears in the woodland the voice of the huntsman? Where is the thatch-roofed village, the home of Acadian farmers,

Men whose lives glided on like rivers that water the woodlands,

Darkened by shadows of earth, but reflecting an image of heaven?

Waste are those pleasant farms, and the farmers forever departed!

Scattered like dust and leaves, when the mighty blasts of October

Seize them, and whirl them aloft, and sprinkle them far o’er the ocean.

Naught but tradition remains of the beautiful village of Grand-Pré.

Longfellow followed the entire history of the Arcadians and wrote of their arrival in Louisiana where they became the “Cajuns.”

Beautiful is the land, with its prairies and forests of fruit-trees;

Under the feet a garden of flowers, and the bluest of heavens

Bending above, and resting its dome on the walls of the forest.

They who dwell there have named it the Eden of Louisiana.

Beyond being an overarching metanarrative, standing for a paradise lost, “Arcadia” has litttle historical connection to the Niagara River and Falls. That said, there is a strong affinity with nineteenth-century American landscape painting and the artists of the Hudson River School who painted in the region. John Pfahl’s Arcadia Revisited: Niagara River and Falls from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario (1988) followed the route of a traveling printmaker Amos W. Sangster who drew the scenic wonders of the same route. It should be noted that Pfahl took his camera and retraced Sangster’s route exactly one hundred years after his predecessor’s portfolio, Niagara River and Falls from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario was published. The years have not been kind to the region, which was already in the process of being spoiled by tourist traffic and by early manufacturers who needed the power of the River. An unnamed author, writing for the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art’s exhibition The Hudson River to Niagara Falls. 19th Century American Landscape Paintings from the New-York Historical Society stated that along this route there were once many attractions for an artist. “The picturesque route along the Erie Canan had included an excursion to Trenton Falls, not far from Utica, a popular scenic attraction deemed second in sublimity, only to Niagara Falls. In a painting (and a print) about 1835, William J. Bennett depicted the series of sensational cataracts that marked the descent of West Canada Creek through a limestone gorge to the Mohawk River. Today these falls no longer exist, having been flooded by a dam built at the turn of the century to provide hydroelectric power. Another scenic destination radically altered by industrial development was the Genessee Falls, whose force was channeled early on to power to mills and factories of what is today the city of Rochester.”

The New York Mirror was very pleased with the engraving, writing, “We have seldom met among the numerous delineators of this stupendous wonder of nature, and conveying a more forcible impression. The sweep of the immense body of water over the precipitous ledges or rocks ” the volumes of foam floating away with the breeze, and everything but the deafening thunder, are represented to the life.” The catalog essay on the paintings along the Hudson River discussed the early views of Niagara Falls continued by stating that “An early view based on sketches made in 1797 by an exiled Frenchman, the Duc de Montpensier, recorded the pristine site as it appeared in the late eighteenth century before the founding of the city. In contrast, William Henry Bartlett’s view, made only four decades later for Willis’ American Survey (1840) recorded considerable “progress,” showing Rochester’s industrial buildings crowding the river at the edge of the falls.“

According to Melanie Zimmer in her book, Forgotten Tales of New York, this Duc was no ordinary French Duc, he was the brother of soon-to-be-king Louis Philippe. After the French Revolution of 1789, the royal son of the Orléans family fled France and went into exile existing precariously in Europe, while his younger brothers were imprisoned, along with their dog, in France. When the Directoire came into power, the three brothers were exiled to America. During this period, Louis Philippe and his younger brother stayed in Geneva New York in the newly completed Geneva Hotel in 1796. “His brother, the Duc de Montpensier, was a skillful watercolorist and painted and sketched many of the sights the brother saw. In fact, Montpensier painted Niagara Falls, which they viewed in June 1797, and later it appears that Louis-Philippe commissioned Romney to paint the three princes in front of the upper falls of the Genesee in Rochester using one of Montpensier’s gouaches as a source. Montpensier’s original is now lost.” The author continued, explaining that this view of the Falls was from the Canadian side. “Montpensier would often make a sketch and create the full painting later, as was the case here at Niagara Falls. The painting was completed in 1804 and hung in the Palais-Royal in Louis-Philippe’s collections.” Today, a painting labeled “after” the Duc is in the collection of the New York Historical Society. The Society states that “The Society’s study is probably the copy commissioned of Louis Phillippe in 1823 from the artist Guillame Frederic Ronmy from Montpensier’s lost original.”

The catalog on the artists of the Niagara Falls mentioned, Louisa Davis Minot, who painted two canvases as early as 1818. According to Katherine E. Manthorne in her article on the “Hudson River,” even by this time, the Falls had a “long history of visual and verbal representation and produced original solutions, conveying the terror of being suspended in the gorge in close proximity to the roaring waters. In 1815, Minot wrote an essay, “Sketches of Scenery on the Niagara River,” in which she said, “the rock shook over my head, the earth trembled..” Minot was traveling in the region shortly after the War of 1812. She “told of the devastation it had wrought on the Niagara region. She surveyed the area, not as a mere tourist, interested in being thrilled by a natural wonder. Rather she was mindful of it as a historic battlefield and comments knowledgeably on the struggle over the terrain by the British, French, Indians and Americans.” The New York Historical Society which owns the pair of paintings noted that “In the early 19th century, Niagara Falls was considered the epitome of the overwhelming sublime, but the tourists walking the rocks clad in fine suits or dresses indicates this landscape was already tamed and accessible.”

Louisa Davis Minot. Niagara Falls (1818)

The next post will discuss the changes to the Niagara River and the Falls as recorded by John Pfahl.