MANET AND IMPRESSIONISM

Édouard Manet’s images of Paris were unprecedented in their unsparing modernity, the sights and scenes that delighted the boulevardier. The painter himself, an elegant dandy, lounged congenially at the Café Tortoni, the Café Guerbois, and especially the Café de la Nouvelle Athènes, where his followers would gather around. Although he studied as an apprentice under the Dutch Masters and Spanish Masters, the painter asserted, “The eye should forget all else it has seen…and the hand becomes guided only by the will, oblivious of all previous training.” The ideal of the “innocent eye” appeared in the guise of a small boy depicted in Courbet’s The Painter’s Studio (1854) gazing at the artist working on a natural landscape. One of the main goals of the Realist artist was to see in a manner uncorrupted by learned habits or by the received wisdom of academic training. In other words, in the time of Courbet and Manet, “representation” meant a system of rules and conventions, all or which had to be discarded in favor of simple observation and a passive recording of what one perceived. Whether or not it was Manet’s intention to free painting from its traditional role of representation, he did in fact create a new system of notation, a system of marks of paint, which (semiotically) signed instead of imitated, thus developing a new language of painting, based upon gestures of paint. Manet understood what had escaped Courbet: if painting/representation was a code or a system of signs, then a new semiotic system of mark making could be created. All one had to do was to learn this new language in which strokes (taches) of paint “stood for” something else.

Édouard Manet. Corner of a Café-Concert (1878-80)

Manet’s rupture with the established way of making art was definitive and final. Once he had pointed out that any kind of mark would do the job, he had sensed the truth that would be iterated by Fernand de Saussure—that the relationship between a word and a thing was arbitrary, bound by a convention based upon a network of relationships among the signifiers. The Academy understood the surface of the canvas to be a window to the world; and, therefore, this “pane” or canvas must be transparent in order to be seen through. The Academy assumed that the marks made by the artist were connected to the object rendered, that the two became one, just like a word acquired the properties of the thing. The assumption was that the formulas that made up the rules of painting would seem “natural” and that the audience had long forgotten that the conventions were a visual language, created during the Renaissance. But Manet created a new language of paint and painting, a system of casual shorthand notation, relying upon the active mind to close the gap between a code and a recreation of that which is rendered. The “languages” created by academic training and by Manet can be compared to the difference between a book and reading every word–the academic system–and scanning key words–Manet. That said, Manet’s followers, the Impressionists, would respond to his method of paining in a variety of ways. Some, like Monet and Renoir, would adopt the broken brushwork to plein air painting; others, such as Berthe Morisot, would apply the sketchiness to an informal modern style. Cézanne would take the idea of mark as “correspondence” and use the stroke to signify a new way of seeing: without the crutch of perspective. All of the Impressionists reacted to the famous “blond” tone of Manet and lightened their grounds and their paint colors, creating a burst of light that shocked the art audience.

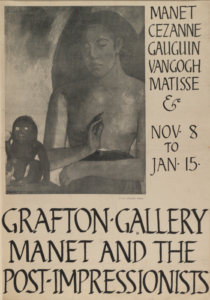

Roger Fry. Grafton Galleries (1910)

It was the English art critic, Roger Fry, who, in his show at the Grafton Galleries in London in 1910, attempted to create a family tree of avant-garde art, starting with Manet and featuring his “descendants.” Manet’s younger admirers were nicknamed the “Impressionists” after a now stolen painting by Claude Monet, Impression—Sunrise (1874). The name was not intended as a compliment but as a condemnation, and, like many names of derision to come, this label stuck. The Impressionists were unusual in that they formally joined together as an incorporated association and exhibited together from 1874 to 1886. The Société anonyme des artistes, peintures, sculpteurs, graveurs, etc. also known as the Impressionists, were a varied group. Claude Monet and Pierre Auguste Renoir were lower middle class men, just one step above working class. In contrast, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt and Gustave Caillebotte were wealthy haute bourgeoisie. Camille Pissarro was working class and an anarchist, while the others were generally apolitical. Alfred Sisley was Anglo-French and was overshadowed by the other artists, and, unlike them, did grow over time or create new content. Paul Cézanne was trained as a lawyer and was notoriously confrontational with the jurors of the Salons until he finally subsided into a self-imposed exile in his home territory of Aix.

The mix of class was not that unusual but the inclusion of women marked the association as different from their all-male predecessors. The mix of class and gender resulted in a variety of content and selection of subject matter among the Impressionists. Largely self-taught artists, like Gustave Courbet, Monet and his painting partner, Renoir, had neither the money nor the inclination to follow Manet and his rich friend, Edgar Degas, into the brothels, the cabaret and to the bals. Likewise, Gustave Callibotte and Alfred Sisley seem to have been too respectable for scandalous subject matter. The American artist, Mary Cassatt and the Parisian artist, Berthe Morisot, were respectable women and were quite restricted in their activities, both social and artistic. Some of the artists produced landscapes, others interiors only, others, like Manet and Cassatt, treated the exterior like an interior. The followers of the Impressionists were, in turn, an equally motley crew. Although there were no women among them, they were all outsider artists. In comparison, the Impressionist women, Cassatt and Morisot, had impeccable training but rebelled against what they had learned. The new generation, including Gauguin and Cézanne, later called the “Post-Impressionists,” was mentored by Pissarro. Impressionist artist and Manet follower, Paul Cézanne had his convoluted and disturbed male fantasies, but he kept them private and on small canvases and honed his craft painting side by side with Pissarro. A devout Socialist, Pissarro rarely left the suburbs to come to the wicked city of Paris, and together the two painters produced a memorable series of landscapes. A Sunday painter and student of Camille Pissarro, Paul Gauguin, abandoned his wife and family and lived his out desire for artistic freedom but kept his sexual passions to himself until his Tahitian period. Vincent van Gogh left his sympathy for the peasant behind when he left his native country of Holland and came to Paris where he saw Impressionist paintings and his palette burst into bright colors.

Mary Cassatt. A Cup of Tea (1880)

The Impressionists emerged in 1874, four years after the fall of the Second Empire. The years that followed the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and the uprising of the Commune had left the nation exhausted and eager to heal. The art audiences had lost patience for controversy and provocation. In comparison to the earlier Bohemians, the Impressionists had no desire to starve or to suffer for their art. They wanted financial success and security, something that could not be found by throwing themselves at the unyielding bulwark of the Salon juries. The Impressionists formed an economic organization, designed to sell art directly to adventurous avant-garde collectors. In contrast to Courbet and Manet, who were transitional artists, committed to the Salon system, both the Impressionists and the Post-Impressionists were true independents, true avant-garde painters, making and showing art completely outside the Salons. Respectable and middle class, the Impressionists and their followers did not seek shocking scenes but showed the contented middle class in its new leisure time activities in a world of outdoor entertainment. With an eye to the art market and possible purchase, van Gogh restricted himself to non-controversial portraiture and landscape paintings. Only Georges Seurat followed Manet and Degas by continuing to celebrate the popular culture of Paris and its dark and sleazy demi-monde. Suburbia or the near countryside, just outside of Paris, were the preferred locales for the outdoor artists, in contrast to the sexually charged interiors of Manet and later, of Degas. Impressionist paintings reflected middle class interests and the domestic needs of the aspiring class. The size of their paintings were small, designed for respectable living rooms, were deliberately decorative and inoffensive, with content free of political contention and sexual scandal.

Gustave Caillebotte, A Game of Bezique (1881)

The Impressionists were not satirical or sarcastic, and only Degas deliberately attempted to be provocative. Unlike Manet, the Impressionists did not consult art historical dictionaries for precedents, nor, after their initial attempts at success, did they attempt to cater to or react against the Academy. Certainly, from time to time, some of the group were tempted to try for acceptance in a Salon but all insisted on painting in their own terms. Unlike Courbet or Manet, the group had no strategy to assault the Academy but sought to create positions in an unguarded commercial field and to make their marks in a completely new territory. Their subject matter was wholly new, completely modern, depicting activities, which had, quite simply, not existed before, such as the new English sport of sailing and the new penchant for the scandalous pleasure of public bathing. Equally unprecedented was the intimate view into the cloistered world of the privileged middle class woman revealed by Cassatt and Morisot with their quite intimate interiors, reflecting the enclosed boredom reserved for females. Also new was the male counterpart to Cassatt and Morisot, Caillebotte’s record of the luxurious lifestyle of well-to-do bourgeois men during the Third Republic. Caillebotte would, from time to time, put the nude (upper-class) male on non-erotic but naturalistic display in invasively private paintings. Deliberately severing themselves from the normal channels of artistic recognition, the Impressionists sought the patronage of the newly rich middle classes through a series of independent exhibitions. It can be said that the Impressionists rejected the Romantic conception of the artist as a poet and accepted the entrepreneurial role of the artist as a business-person and upwardly mobile worker.

Like Manet, the Impressionists reveled in modernité described so unforgettably by Charles Baudelaire in The Painter of Modern Life. Every touch or tache of the brush, each casual mark evoked the “fugitive” and the “ephemeral” aspects of an ever-changing urban environment. Stressing the generation break with the older Realists, the Impressionists were uninterested in the country life celebrated by Gustave Courbet and Rosa Bonheur and showed the blunt newness of a post-war industrialized Paris. The Impressionists reached out to the middle class audience by concentrating on the familiar aspects of city life, the newly developed suburban areas, and the accompanying novelties of respectable entertainment. The male artists inherited the attitude of the city-dwellers who enjoyed a “Day in the Country,” a weekend excursion now possible because of the spread of a network of suburban railway lines that took the Parisians away from the City of Light. The female artists developed new content about the “modern woman” who was confined to quarters, living a life of caged privilege. Courbet and Manet had led the way in their use and appropriation of popular imagery, such as the images d’Epinal, and the Impressionists were equally interested in popular posters and contemporary art and attempted to combine popular iconography with experimental style. With the Impressionists, the subject matter or content they selected was as provocative as their revolutionary sketchy style of the plain-air painters, such as Sisley, born of a necessarily hasty execution.

Impressionist paintings also utilized Dutch and/or Japanese compositions combined with careful optical examination of color and light that alienated them from mainstream art. Like their predecessors, the Impressionists admired the ordinary vistas and high horizon lines of Dutch landscape painting. Many art historians have claimed that the arbitrary cropping of amateur photography may have had some impact upon the Impressionists, but a careful review of nineteenth century photography suggests that photographers preferred centered compositions. It is likely that the art historians, many of whom formed their theories in the wake of vernacular photography in the 1960s, are reading Impressionist paintings anachronistically. The combination of the centered subject and the unavoidable slicing off of elements on the edge seen in Impressionism most likely came from Japanese art. The Ukiyo-e prints, imported from Japan, were erroneously called “Chinese” at first by the French who thought of the Japanese, and all Asians as, “primitive.” The Edo period prints, collected by the Impressionist artists who thought the brightly colored scenes of daily life to be master works of a naïve vision, were actually popular prints with little value in Japan. Influenced by their exposure to Western art by the Dutch traders, the Japanese artists interpreted Western perspective as the abstract design it actually was. To the delight of the French artists, the Ukiyo-e prints played with high viewpoints, insistent horizontal banding and spatial ambiguity. It was Degas who exploited Japonisme, the historical back-and-forth between Eastern art and Western art, in his paintings of ballet dancers.

Edgar Degas. The Dance Class (1873)

As this general summary of Impressionism indicates, the movement and its art was a complex manifestation of manifold positions and varied influences. With Édouard Manet as their leader, the Impressionists followed his stylistic example but not his journey into the Salon. The Impressionists persuaded Manet to leave his studio and to venture out into the sunlight where he produced a few landscapes. But Manet and the Impressionists came from different generations. Manet was a dandy, a survivor of the Second Empire, while the Impressionists were sons and daughters of the political patchwork called the Third Republic. The result was both an extension of the Master’s painting and a rejection of Manet’s subject matter. Often presented in terms of landscape painting only, as a movement of broken brushwork only, the movement was actually quite varied in both style and content. There are many ways to view Impressionism: as a formal revolution in painting, as a contrast between the lives of men and women, as an early foray into the art market, and a study of how artists mature over the course of long careers.

See Also:

“Impressionism: Class and Gender”

“Impressionism and the Art Market”

“Impressionism and the Landscape”

and the Podcast “Manet and Impressionism”

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.