Marc Chagall in Moscow

The Murals for the Jewish Theater, Part Two

Perhaps because he was the first to visually imagine a totally Yiddish world, mystical and magical, sophisticated and folkish, avant-garde and traditional, Marc Chagall’s ability to capture the modernity of a new Jewish identity left a mark on Yiddish theater in Moscow. The Moscow State Yiddish Theatre (Moskver idisher melukhisher teater) also known as GOSET became a staging ground for the incorporation of Yiddish culture into mainstream Russian society. Chagall was “present at the creation,” as it were and his unique and distinctive vocabulary and his iconic imagery made a powerful impression upon both artists who had to follow in his wake and upon delighted audiences. Abram Efros, the art critic, wrote in 1922 of the extraordinary experience of viewing the collaboration between Alexi Granovsky and Marc Chagall,

Oh, that Yiddish theater!–without a foundation or a roof, without borers to its domain or any blueprint! A theater that is its own grandfather, father and son. A theater that has not yet any past, present, of future, and that must create for itself a past, a present, and a future. A theater that has to live simultaneously in three dimensions of time. A theater with no tradition, but which has to invent for itself a historical time line; a theater without a present, but which has to be at the cutting edge of contemporary theater art; a theater without perspective, but which has to old the form of what is to come.

A sponsor and supporter of Marc Chagall, Efros was one of the first to write of the excitement of presenting Yiddish culture after the new Soviet Union, under Lenin withdrew from the Great War. Suddenly all restrictions on Jewish movement and upon Jewish cultural expressions were withdrawn and opportunities presented themselves to artists like Chagall who now had the possibility of creating the foundational visuals of Yiddish culture. The artist, fresh from his humiliation in Vitebsk, rallied and produced a series of murals, which turned a confiscated home into an enveloping work of art, a backdrop against which the beloved stories of Sholom-Aleihem were performed. Efros noted that the State Yiddish Chamber Theater both benefited and paid for the success of Chagall, who proved to be a hard act to follow. The critic wrote that the artist “did not..accept any directions..” and that Chagall “forced us to pay the most expensive price for the Jewish national form of scenic expression..in the end, the young Yiddish theater struggled because of this victory.” In 2009, Mel Gordon, professor of theater arts at Berkeley, noted that the Moscow Yiddish State Theater was the most successful theater of its time, even though the majority of the audiences did not understand Yiddish. Gordon pointed out that although Chagall mounted only one production in 1921 at the GOSET, he marked the theater with “Chagallism,” the “touch that utterly changed” the theater group and “created a new art form.”

Gordon revealed that Granovsky–a child of a wealthy family–did not speak Yiddish, which was “lower class” or vernacular, and had no interest in Yiddish culture, but he found himself in Russia after the Revolution, a nation that no longer spoke the enemy language of German. Nevertheless the director wrote of the new theater in a brochure: “Yiddish theater is first of all a theater in general, a temple of shining art and joyous creation — a temple where the prayer is chanted in the Yiddish language.” Many Jews who came to Moscow were Russian speakers but were eager to support their own culture and didn’t seem to mind if they couldn’t understand Yiddish. This simple fact encouraged Granovsky to create the kind of theater that depended upon visuals rather than upon dialogue, making of the Yiddish theater a optical spectacle that allowed the viewers to follow the stories thought gestures and postures which provided plot and action without words. The best way to explain this new form of acting, or “spots,” is to compare the plays to the fragmentation of Analytic Cubism.

Sadly, Granovsky and Chagall were unable to see eye to eye. The conflict was unsurprising, given that Chagall had a deep understanding of Yiddish culture and Granovsky was expecting an “origin story” of Yiddish culture which existed on a higher plane. Chagall understood that Yiddish culture was a distinct folk culture, cut off from elite culture, and knew first hand that the Jewish culture was down to earth and even vulgar and obscene and offensive. In comparison to urban Jews throughout Europe, the Russian Jews, unless they were wealthy and privileged, were unassimilated and alienated. Therefore, it could be concluded that the Yiddish culture was “authentic” and unalloyed by outside influences. Chagall’s vision of ghetto and shtetl popular culture as evolved by a peasant culture of lower class people was seriously at odds with Granovsky, who had higher ambitions, derived from his apprenticeship with Max Reinhardt, and expected perhaps an idealized and sanitized rendition of what an outsider would have preferred “Yiddish” to be–not quite so alien and ungoverned.

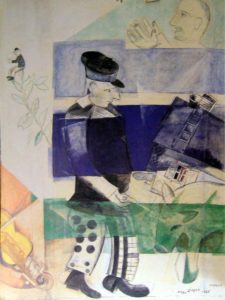

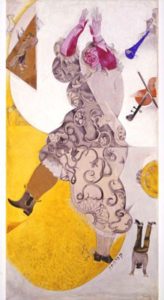

As autobiographical as always, Chagall depicted himself and his family and the relatives who lived in Vitebsk and Lion and wrote the names of his numerous relatives into patterns on the trousers of a clown who played a flute. The frieze above the windows portrays a wedding, a highlight of Yiddish culture, a guarantee that the Jewish people will continue as a unique group. The wedding was a continuous feast, an endless celebration symbolized by food, paschal hala and New Year’s dishes. Below the entirety of a Jewish year, are a series of four personifications of Yiddish culture, set between the back windows. These narrow spaces were inhabited with the klezmer or the musician and the badchan or wedding jester and the svacha, a dancing woman, all of which appeared as allegories for creativity in the performing arts. The icon for Poetry was a sofier, or the scribe who copied the Torah in the peace of his private quarters.

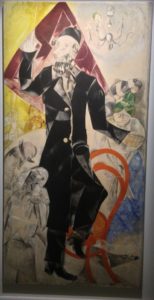

A “bodkin” at a Jewish Wedding also known as “Drama”

By using these apparently stock figures in Yiddish culture, Chagall, the son of the shtetl, introduced a defiant authenticity into the theater with his use of “bodkins” or Jewish comedians whose humor was vulgar and homophobic and did not invite laughter. In addition, Chagall insisted that, contrary to Russian expectations, Jewish literature did not emerge from religious documents, but from folk tales or “grandmother’s tales,” oral tradition, as recreated by Sholom-Aleihem. Because he was revered and accepted by both Russian and Yiddish speakers, Sholom-Aleihem, who made the choice to write in Yiddish, was a wise choice for the first event of GOSET. According to the 1993 Guggenheim exhibition of the murals,

Through a natural outgrowth of his painterly vocabulary, Chagall presented a kaleidoscopic panoply of ecstatic figures in this work, which suggested an anti-rational model of carnivalesque abandon for the theater. This conceptualization of theater was not entirely new; Russian directors such as Vsevolod Meierkhol’d and Aleksandr Tairov were exploring the legacy of commedia dell’arte and other popular theatrical spectacles before Chagall began work on the murals.” Granovskii was already disposed to that kind of dramatic treatment through his studies under Max Reinhardt, the progressive Austrian director. Yet Chagall presented a unique, and uniquely Jewish, approach. Through specifically Jewish visual puns, Yiddish inscriptions, and references to the festivities of Jewish weddings and Purim — a Jewish analogue to carnival in its emphasis on ludicrous masquerades and outrageous intoxication — he posited a distinctive model for the Jewish Theater.

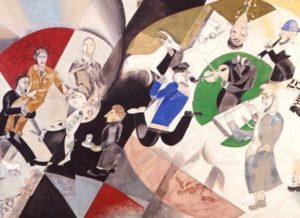

Marc Chagall. Introduction to Jewish Theater (1921)

In order to understand the “Chagall Box,” it is necessary to view the murals by the artists as both contrarian and as revelatory of a long hidden culture of lower class rural Jews. Appearing between the windows at the back of the theater as a rectangular “portrait,” the “bodkin,” according to Gordon, was a “sour” comedian who was featured at Jewish weddings with the task of overturning convention and even decency. The bodkin would make the bride and groom cry, if he was good at this job, that is, and he would direct his most cutting remarks to the wealthiest and most successor and most smug residents of the ghetto. In other words, the bodkin was a leveler and created a moment of the carnivalesque, when conventions were inverted. The charivari was a Medieval European custom which was a subversive upending of the expected norms. To this day, in some parts of Europe a charivari will disturb the wedding night of a bride and groom. This counter culture, the antithesis to elite courtly behavior, was vividly depicted by Chagall on his twenty-five foot mural, Introduction to Jewish Theater, where he deliberately conflated Yiddish culture with Yiddish theater with its source of origin, the irreverent bodkin, to the often scatalogical and male culture of urinating and farting.

Detail of “Introduction to Jewish Theater”

The question is why did Chagall assert such a strong vision of Yiddish culture, unadorned and unadulterated, presented in a “popular manner” or folkstimlekh? Why was he not more tactful and and cautious in his “Introduction?” The answer probably rests in the mood of the Jews in Russia after the Revolution. For the newly freed Jews, the insertion or absorption of Yiddish or Hebrew cultures of the “masses” into the fabric of Russian culture was part of the Revolution itself. In making Jewish life part of a pan-Russian society, intellectual and political Jews, like Marc Chagall, insisted on bringing society into a state of equality. Therefore, in Chagall’s murals, we can read an insistence of equivalency of high and low culture and a refusal to censor or subdue aspects of the shtetl. Indeed as Benjamin Harshav pointed out, the theater was guided by two leading principles: “theater as Art” and “theater of the State.” Therefore, the characters created by Sholom-Aleihem and Marc Chagall are tropes or character types, exaggerations of iconic figures well-know and well-honed over centuries, such as the hapless schlemiel.

“Music” as personified by the Green Fiddler and “Literature”

In the book, Marc Chagall and His Times: A Documentary Narrative, by Benjamin Harshav and Barbara Harshav, it was pointed out that

The dense traditional culture of the Jewish religious world was now seen as folklore, a source of vitality, imagery, and folk wisdom that can be recycled into the modern, secular world, as Chagall tried to do in his murals for the Moscow Yiddish Theater. For a while, Chagall participated in this revival, he even restored his presumed original family name, and signed several paintings “Moyshe Segal.” The vast mural which “introduced” the origins of Jewish theater to the Moscow audience can be read from left to right–in Russian fashion–or from right to left—in Yiddish fashion, but in between is an antic display of dense imagery that needs to be read in terms of what the authors term “Jewish folk semiotics.” Quite different from the logic of Enlightenment thinking, this semiotic system reflects “a mind of associations that perceives events as situations and images parallel to one another in a global universe, rather than points in a causal chain, a narrative sequel with precise, rational chronologies. This traditional Jewish folk semiotics derives from the perception of post biblical Judaism, that after the destruction of the Jewish state and the close of the Bible, history was over; that their is a totality of beliefs above all and any history and geography; that the Jews are a chosen and persecuted nation irrespective of the changing powers and politics, and nothing changes until the Messiah comes..Most traditional Jewish texts lack a narrative direction (except for the short stories embedded in them); that is, every detail is not a link in a chain of events, but is significant outside of its context, in a total universe of meaning. Hence it needs interpretation rather than counting. And this atemporal world perception and significance of every detail was internalized in Jewish folklore and behavior.

Detail from “Introduction to Jewish Theater,” featuring Chagall on the far left being carried in by Abram Efros.

Chagall did not stay to savor his brief triumph in the theater and left Russia in 1922 and did not return until 1973. Discouraged at the state of the art world, he wrote, “Neither imperial Russia nor the Russia of the Soviets needs me. They don’t understand me. I am a stranger to them. I am certain Rembrandt loves me.” Indeed Granovsky found that Chagall was trouble, “taking liberties,” and was unmanageable and was unable to comprehend the profound impact the murals would have upon theatrical production in Russia. Another designer, Nathan Altman was asked in 1922 to design sets and costumes for The Dybbuk, and Chagall was passed over. When he saw the performance, he felt that Altman had copied his conceptions from 1921 and translated them to a watered down version of his (postmodern avant la lettre) view of the Jewish world. He wrote, “Those five years churn my soul. I have grown thin, I’m even hungry.” Thanks to Lunacharsky, his old friend, Chagall was given permission to leave the Soviet Union, ostensibly to deliver art works to Paris. He was forced to leave without his wife, Bella, and their only child, Ida, but they joined him later in 1922. In 1924 the murals were moved to a new site, a concert hall more suited for theatrical productions. During these years, avant-garde art and Jewish culture was gradually purged from the Soviet system by Stalin. Few of Chagall’s associates, friends or enemies colleagues survived the purges and censorship of the thirties and he alone of the Russian avant-garde left to paint in freedom in France.

![]()

The Wedding Feast Frieze (1920)

Tempera, gouache and white highlights on canvas, 64 by 799 cm. State Trtyakov Gallery

Through a miracle, Chagall’s murals were preserved in situ until they were hidden away in 1937 by an admirer, Alexander Tyshler. In the post-Stalin era, Tyshler turned the murals over to the Tretyakov Gallery in August of 1952 where they remained for the next twenty years. The artist had little hope that he would ever see the murals again and in fact, until 1973, this important body of work was unknown to the West. To Chagall’s joy, the seven murals, painted on the floor in goauche and tempera on canvas in forty days, had been removed from the walls and saved. The canvases were wrapped around drums which preserved the fragile painted surfaces. Chagall signed and dated the murals, interestingly enough in Russian, and from 1989 to 1990 they were restored at the Fondation Pierre Gianadda in Martigny, Switzerland and exhibited at the Guggenheim Museum in a landmark exhibition of 1992-1993.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.