Marc Chagall and the Revolution

Vitebsk as an Art Center, Part Two

A quiet and gentle man who loved his wife and cared for his family, especially his newly arrived daughter, Marc Chagall (1887-1985) was an unlikely revolutionary. In fact, his position was not unlike those of the other Russian artists, writers, academics and intellgentsia, suddenly freed from the Czarist regime. Between the February and October revolutions of 1917, little changed as the news of the ouster of the only ruler most Russians had ever known rippled slowly across the vast expanse of the former Empire. But the cultural leaders were poised between a new awareness of possibly having a new mission and lack of direction and it would be up to people like Chagall to transform the political revolution into a social revolution. Unlike the American Revolution which happened gradually over decades, the end of the Empire in Russia was abrupt, even arbitrary. The Communists, the Red faction, had, of course, been planning for an overthrow, but the final collapse is usually random in any revolution. First, the break needs to happen and then, second, a leader has to emerge and then–and this is the point where the artists emerge–lastly, a discourse, both verbal and visual needs to be constructed.

Lenin during the October Revolution

The February Revolution, which due to the eccentric Russian calendar really took place in March, was marked by the abdication of the hapless Nicholas II and the installation of an equally hapless Provisional Government. The mere word “provisional” would freeze innately cautious intellectuals who would hope for a freer education, unshackled from the regime’s control but would not be included to venture further, even thought the police state had been (temporarily, as it turned out) suspended. As R. Service noted in Society and Politics in the Russian Revolution, the elite was interested in serving the “dark people,” or the uneducated masses.

One attempt was made by the cultural-educations section of the Moscow Soldiers’ Soviet in early 1917. An appeal was made to “partners, sculptors, artists, poets, musicians and architects,” who were called upon to respond to the enthusiastic upsurge of interest in and opportunities for cultural advance. it was hoped,that, in the special circumstances of the sin of the great war between peoples, those responding to the appeal would throw art a lift belt. Initiatives of this sort led to the formation of Proletkul’t (proletarian culture) in the days immediately preceding the October revolution. Its chief luminaries, (Alexander Malinovsky) Bogdanov and (Anatoly Vasilyevich) Lunacharskii, had been involved in cultural-educational work in a variety of ways.

Service wrote about the difficulties of merely surviving during the early years of the revolution, but Chagall, who was safely stowed in home town, does not seem to have been among the intelligentsia who were burning their furniture for firewood. True, like other artists, he witnessed his patrons fleeing with their collections to safer locations but he had a home to go to. Even though Chagall enthusiastically supported the Revolution, prudently, when the October revolution brought down the Provisional Government and ushered the Bolsheviks into power, Chagall slipped quietly out of Petrograd and retreated to the safety of Vitebsk. When his old friend from La Ruche in Paris, Lunachrskii, was appointed Commissar of Enlightenment, Chagall was unexpectedly in line for a more elevated position than that of a small town artist. During the War years, Chagall produced a remarkable body of work, half truth, half fiction, half document, half dream, which preserved a record of Vitebsk, a traditional Jewish town of the Pale that would, later on in the century, lose its distinctive culture. As a Jew, Chagall, was suddenly empowered in the new Soviet era being placed on the same legal footing as other Russian citizens. In the newly colorful language of the new age, the painter was dubbed the Commissar of Art in Vitebsk and opened the Peoples Art College, dedicated to expanding education beyond the elite.

Narodnoy Khudozhestvennoye Uchilische

This new appointment was not exactly bestowed upon a passive Chagall. In fact, as time passed, he began to sense a shift in the winds of art, away from the European cubist-based avant-garde and towards proletarian art, or an art of native Russia. The artist was uniquely placed to take advantage of the need of the new regime to educate the lower classes–he spoke the language of the people. His Lubok style paintings were not just ethnically Jewish but also distinctively “folk” and uniquely Russian in a way that the “people” could receive. Chagall, who had previously been offered a prestigious position, realized that a real opportunity presented itself and the man rose to the moment. After returning to Petrograd, Chagall accepted the offer to run an art school in Vitebsk and returned home with a title and a position. Although the Russian avant-garde artists could not see into the future, in hindsight, the next few years would be remarkable ones. The new Bolshevik government would be preoccupied with putting down the White Army, while at the same time, extricating themselves from the ongoing war, and, during this interim period of little oversight, the artists could dedicate themselves to developing a new art for a new world and they could do so in their own terms. Once the government had settled its affairs, both with the civil war inside and the external conflict, Lenin’s successors began to examine the usefulness of cultural production to the government and the aims of Marxism. Censorship would soon follow.

For someone reluctant to work for the government in Petrograd, Chagall threw himself into his new role as the artistic leader of the city of Vitebsk. He was consumed, he said, “with the prodigal spectacle of a dynamic force which pervades the individual from top to bottom, surpassing your imagination, projecting itself into your own interior, artistic world, which seemed to be already like a revolution.” His appointment to his new post was in September of 1918, meaning that his first task was to stir the city to celebrate the first anniversary of the October Revolution. As Chagall himself reported, the city was painted in bright colors and festooned with four hundred and fifty posters (other sources cite three hundred and fifty) and flags and grandstands and arches were built to receive parades. Chagall’s posters were memorably colorful, combining whiffs of the avant-garde with imagery that the citizens of Vitebsk could grasp. At night the new Communist banners, complete with hammer and sickle, were flooded with light, stunning the citizens.

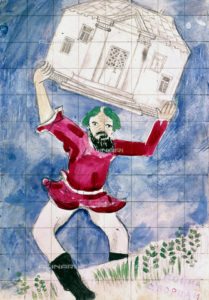

Marc Chagall. Peace to the Shacks War on the Palaces (1918-1919)

Baffled Party officials did not understand Chagall’s folk approach to a political revolution, but the inhabitants of the city were excited by art that was everywhere, brilliant and happy and celebratory of the lower classes and rejoicing in the new freedom from tyranny. Indeed the proletariate nature of the display of art for the people, provided by the town’s most famous artist, foreshadowed the mission of the art college. The old idea of an “academy” with all its old-fashioned elitism would be obliterated to be replaced with a school that would be dedicated to communicating with a wide audience of common people. However, Chagall was not interested in continuing old folk ways and indicated that a new art needed to be simple, meaning that a direct and straightforward approach would replace the genre and narrative works of older artists, such as Yehuda Pen.

Chagall and His Students in 1919

The People’s Art College (Narodnoy Khudozhestvennoye Uchilische) combined a non-exclusive approach to teaching and learning art with a sophisticated notion that artists should be encouraged to experiment, in an avant-garde fashion, in studios located at the school. To incorporate all points of view, Chagall invited well-known artists from Moscow, the couple, Kseniya Boguslavskaya and Ivan Puni and El Lissitzky to teach drawing, applied arts, graphic design and so on. With such distinguished teachers, the People’s Art College quickly swelled to two hundred students–mostly male. Chagall, rather bombastically, proclaimed, “..thanks to the October Revolution, it was here that revolutionary art with its colossal and multiple dimensions was set into motion.”

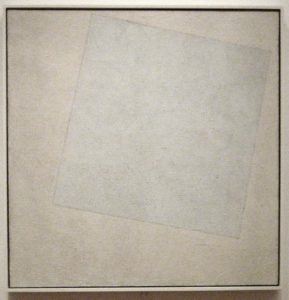

Kazimir Malevich. White on White (1918)

Having made “art descend to the streets,” Chagall’s triumph was followed by tribulations with the professors, some of whom simply drifted away from the school and other, such as El Lissitsky and his associate Kazimir Malevich, directly challenged Chagall for leadership. This agon between Chagall and Malevich is clouded by history and the passage of time and obscured by Chagall’s refusal to elaborate, but it seems obvious that the leader of Suprematism and the painter of Vitebsk would have totally different ideas of what art after the Revolution should be. Malevich, as is well known, was a deeply theoretical artist, combining Theosophy and semiotics to create his endpunkt for painting, and Chagall’s naturalism and charm infused Jewish themed paintings seemed neither revolutionary nor advanced to Malevich. In response to Chagall’s regressive art, Malevich formed UNOVIS, or in other words, he gathered students around him and supplanted the authority of Chagall in an internal coup de tête.

On one level, the quarrel between Chagall and Malevich was yet another parochial and internecine joust among academics–common to colleges–on another level, the question of which kind of art would be the most suitable for a nation in revolution was one that would continue to plague, not Chagall, but the avant-garde artists, who would find themselves increasingly at odds with the government’s expectations. That said, there is ample evidence that Chagall was not a good administrator or a tactful manager of the fledgling school. He had his own student followers but he was no match for Lissitsky, an ally of Malevich, who quickly joined (0r formed) anti-Chagall factions among the students and began moving against Chagall’s leadership. The new revolutionary faction intimidated the students loyal to Chagall while the local soviet officials and the newly revived secret police prowled suspiciously around the school. Threatened everywhere and showing little taste for petty combat, Chagall chose to not stay and fight to keep the art school he had founded.

Marc Chagall. Over the Town (1918)

In his own way, in the eyes of the new government, he was a more famous artist than Malevich and Chagall was able to leave honorably for Moscow to fulfill a commission. What he left behind, in 1920, were the beginnings of a war on the intellectuals, the next stage of leveling society, favoring the proletariat over the elite. Chagall’s in-laws, Bella’s family, left for Moscow after their home was ransacked by thugs, loosely sanctioned by the government, searching for treasures. Although Chagall was deeply embittered by the betrayals he suffered in Vitebsk, his experiences and the events that were roiling the town and the art school were also straws in the wind. Alert artists and intellectuals with foresight saw the warning signs and began to exit the newly repressive and unstable nation. However, Chagall had one last give to give his native country before his final exit–a famous and deliberately obscured expression of Jewish culture to be discussed in the next post.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.