IMPERIAL PHOTOGRAPHY

Maxime Du Camp (1822-1894)

The Camera’s Vision

Photography inherited the conventions of painting and these conventions are artificially organized into hierarchies that emphasize contents according to the subject matter. Other objects are subordinated to the main theme and function only in relation to the overall content. Here in the controlled universe, nothing is wasted, all exists out of necessity. In contrast, with photography everything–all elements–exist out of necessity, the necessity of non-selection, the characteristic of camera vision. These specific properties of the new medium, then, would seem the perfect kind of vision for this point in time. The middle of the nineteenth century was the age of positivism and empiricism par excellence. The impersonal approach allowed by the camera could be though of, at this time, as the equivalent of scientific vision, but with far more exactitude and precision. No detail could escape and there was no room to interpret or to read meaning into the surface information which raised a veil against the imagination. Photography fulfilled the dream of the French historian Hippolyte Taine (1828-1893) who said, “I want to reproduce the objects as they are, or as they would be even if I did not exist..”

But photography was invented in the fold of Romanticism and Realism, between imagination and scrutiny of reality. The early practitioners simply followed, as best they could, the conventions of sketching and painting, which provided the aesthetic criteria and established appropriate subject matter. At first there was apparently no conception of what a photograph was, what it could do in its own right; there was little speculation as to what its essential nature could reveal of its potential. Over time photography began to develop different artistic skills and attitudes on the part of the operators. A new version of the partnership between the eye, the hand, and the brain began to be develop. In contrast to the camera’s lack of selectivity and its mechanical mindless recording without the trained “hand” actively in play, the eye, guided by the brain becomes the agent which scans, selects and makes conceptual decisions with actually foreground the mental operations of the artist. That said, it is rare to find a photographer who both staged and directed photographs without actually intervening with the camera’s vision.

Ever since Napoléon Bonaparte (1769-1821) briefly conquered Egypt in 1799, the French had been fascinated with the mysterious East as this distant and exotic place, holder of mysterious and ancient secrets. The psychological phenomenon of Othering an entire region is known today as Orientalism but in the middle of the nineteenth century, the Near East was a site of imperialism. “Orientalism” was a means of naming and thus controlling a region that could not be understood in its own terms but only in its relation to Europe. To the European these “unknown types, unpublished races,” as writer Théophile Gautier (1811-1872) expressed it were to be conquered and studied as specimens. As early as the 1830s, French engineers had approached the governor, Mohammed (Mehmet) Ali, about creating a canal at Suez, but, despite his interest in modernizing Egypt, the ruler was not interested, assuming correctly that such a strategic trade route would only but his power at risk from other European powers. Indeed, France had a long history of supporting Egypt against the Ottoman Empire and its ally, the British.

Maxime Du Camp

It could be said with some caution that Maxime Du Camp was one of the first pure documentarians to attempt to produce a photographic project inspired by the empirical determinants of scientific research. His work falls in an uneasy zone between the “imperial eye” and the “camera eye.” By 1849, the year Du Camp decided to go to Egypt, the country was ruled by Abbass Hilmi, the grandson of Ali, who reversed the historical preference for the French in favor of the British. It can be assumed that Du Camp was less interested in contemporary international politics than in the ancient history and the harem beauties of Egypt. Already a world traveler who had written Souvenirs et Paysages d’Orient: Smyrne, Ephèse, magnesia, Constantinople, Scio in 1848, Du Camp had dedicated to his close friend Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880). On this journey to Egypt, he decided to take a camera with him, an interesting notion, given that Du Camp was enamored with the Romanticism of Victor Hugo (1802-1885). But he was determined to make a photographic, rather than a literary journey, switching from a literary interpretation or a written Orientalism to a pseudo-scientific approach to Egypt.

Gustave Flaubert

It is a measure of how easy it was to learn photography during the first decades that the writer Maxime Du Camp could simply take a few lessons from Gustave Le Gray (1820-1884) and embark on a trip to Egypt, photograph landmarks, return to France and produce what was the world’s first travel book and then retire from photography, enjoying his fame as a photographer. In 1849 the Calotype process was still new to the French and Du Camp was not satisfied with Le Gray’s use of the paper process and he learned how to wax his papers through the photographic publisher Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard (1802-1872). But within a few weeks, Du Camp considered himself proficient enough to convince the French government to support a photographic tour of Egypt and the Holy Land.

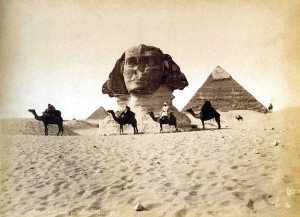

Du Camp was independently wealthy but he approached the French Ministry of Education for its sponsorship, which would elevate the exhibition from tourism to science. His traveling companion and fellow Romantic enthusiast, the then fledgling novelist tall, blond, and handsome, Flaubert was so fixated on “the Orient” he considered this fabled land his spiritual home, but strangely enough he had been tasked by the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce to collect information for business interests. Both young men were rich and privileged and spent two years enjoying themselves as tourists, sexual adventurers and documenters of ancient sites. Accompanied by a young poet, Louis Bouilhet, and the languid Flaubert, the efficient Du Camp focused on photographing the pyramids, the sphinx and other Egyptian monuments, following a map marked with points of historical interests. In other words, it was his intention to record a tourist’s eye view of ancient Egypt in European terms, a romantic adventure already ready, packaged for the wealthy traveler.

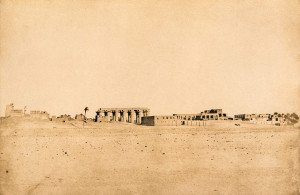

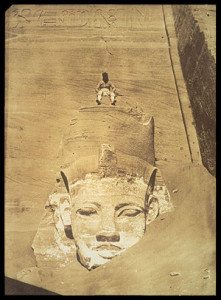

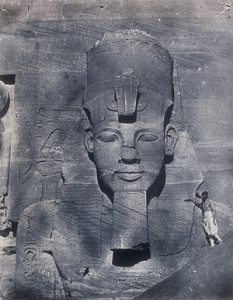

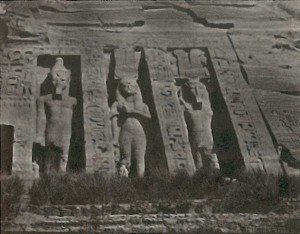

Certainly this venture received so much governmental support because of France’s imperial interests in Egypt and Syria. It should be noted that in 1849 both France and Egypt were in transition, exchanging one ruler for another and it is possible that the French had not yet realized that their fortunes in Egypt were on the downturn. Indeed Flaubert and Du Camp were well received by the Egyptians who still favored the French and were warmly welcomed by the newly installed Abbass, something that would have been problematic a year later. On their twenty-one-month tour, Du Camp, who worked systematically in an archaeological mode made two hundred and twenty Calotypes, wrote copious notes and educated himself on Islam. Many of his photographs of Egypt contain a figure of a male, Hadji-Ishmael, who served to give the French reader a sense of the scale of the monuments.

In her 1993 essay, “‘La Maison démolie:’ Photographs of Egypt by Maxime Du Camp 1849-1850,” Julia Ballerini quoted Du Camp’s colonializer domination of the colonized “native.” As Du Camp unblinkingly wrote,

The great difficulty was to get Hadji-Ishmael to stand perfectly motionless while I performed my operations; and I finally managed it be means of a trick..I told him that the brass tube of the lens jutting from the camera was a cannon, which would vomit a hail of shot if he had the misfortune to move–a story which immobilized him completely, as can be seen from my plates.

Hadji-Ishmael described as handsome by Du Camp was a sailor who was part of his crew of his boat and, according to James S. Ackerman, in Origins, Imitation, Conventions: Representation into Visual Arts (2002) provided him with “suitably Oriental costumes.” Du Camp’s near manic determination to record his work with words and images may have had something to do with the fact that, by the time of this journey, he was not yet thirty years old, but his family had died, one after another, leaving him an orphan alone in the world. Du Camp observed everything and recorded as much as he could, as if to stop time and to freeze its passage. But whatever passion that drove his accounting, Du Camp allows the camera to do all the work. What we see in the photographs of the Near East is almost pure camera vision, alienated only by the occasional insertion of human figures for referential purposes. Certainly Du Camp could have asked for Flaubert, for example, to provide a human presence an the fact that he did not implies that he used the young sailor in a de-humanizing fashion, as a human measuring stick, intended to provide information and to disappear.

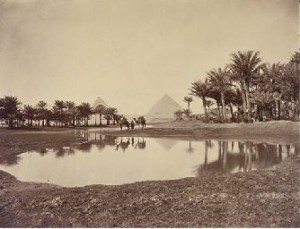

It is clear from looking at Du Camp’s work that he may have been a photographer, he was an uninspired one, lacking any artistic imagination of aesthetic sense. Of course, unlike the Calotype photographers of France, he had no artistic training and through of photography as a camera recording ancient monuments from an archaeological perspective. For a devotee of Romanticism, Du Camp strangely scours his images of the mystery that so fascinated his time. A member of the Société orientele, he promised documentation and his images are seldom anything more than flat-footed. The image of the pyramid below is a rare attempt on his part to convey the “romance” of Egypt.

Du Camp had to continue his lessons in photography as he worked. The light in Egypt was much brighter than that of France and there were no light meters at that time. He had to guess and work by trial and error to determine the appropriate exposure time, an aggravating process of failure before finally achieving success. As Du Camp himself wrote, “If, some day, my soul is condemned to eternal damnation, it will be in punishment for the rage, the fury, the vexation of all kinds caused me by my photography.”

Flaubert’s travel notes recounted the expedition’s first glimpse of Sphinx:

About half past there we are almost on the edge of the desert, the three Pyramids looming up ahead of us. I can contain myself no longer, and dig in my spurs; my hours bursts into a gallop, spacing through the swamp. Two minutes Maxime follows suit. Furious race. I begin to shout in spite of myself; we climb rapidly up the the Sphinx, clouds of sand swirling about us. At first our Arabs followed us, crying “Sphinx! Sphinx! Oh! Oh! Oh! It grew larger and larger, and rose out of the ground like a dog lifting itself up.

Du Camp’s struggles with the basics of photographing in Egypt would be characteristic of those suffered by photographers who came after him. As primitive as his paper photography may have been, the basic chemistry was an advantage over the more complex chemistry of the more “advanced” collodion process. Du Camp did not need a van to transport his equipment and his chemicals were not as inclined to boil over in the hot sun. The sheer difficulty of photographing in in hospital climates could account for the rather small number of successful prints for two years of work.

Du Camp’s images of Palestine and Syria are less famous and less available today, but, as these photographs of Jerusalem indicate, he approached the Holy Land with the same dogged stance he had taken in Egypt. His position is frontal and informative, with the object of interest centered, taking up the frame fully, opening the architectural monuments to the gaze of the armchair traveler.

Certainly there was a readership for Du Camp’s photographic project. France had been fascinated particularly by Egypt for decades but the possibilities for travel were very limited, due to the difficulties of actually getting to Africa and Asia and the constant wars and governmental uprisings. After half a century of conflict in France, Du Camp managed to make his journey during a rare quiet period not just in his homeland but also in the Near East. A treaty just forced upon Egypt by England had forced Egypt to give up its struggle with the Ottoman Empire over the domination of Syria. Syria was given back to the sphere of the Empire and, in return for relinquishing this prize, the rulers of Egypt were allowed to pass on power through an orderly secession of inheritance (which often included murder to hurry things along). Du Camp’s photographs eschew contemporary politics and the world he presents is a world of the Bible and a world of imperialism, a dream of a crumbling and backward ancient world badly in need of eurocentric European intervention.

When Du Camp returned to France he attempted to print out his own images but was plagued by problems of fading. Once again he turned to Blanquart-Evrard for assistance and the printer took over the task and used albumen to fix the tones. In the end only half or one hundred twenty-five of his Calotypes were printed by Louis-Desire Blanquart-Evrard (1802-1872) and published in 1852. Printed in an edition of two hundred high priced volumes, Egypte, Nubie, Palestine et Syrie was the first book about the this area of the world to be illustrated with actual photographs. After his return, Du Camp put aside the troublesome camera and gave up photography, devoting his time to writing.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.