PRESERVING THE PAST

Mission Héliographique: The Project

Part Two

The invention and development of photography straddled a transition period in both French and English art. The fact that photography was developed in the gap between a declining Romanticism and a rising Realism was of little concern to the vast majority of the commercial photographers who used the Daguerrerian method as the foundation of their business in portraiture. But for artists who wanted to explore the possibilities of photography, the gap was an interesting one and manifested itself in paper photography, the realm of artist-photographers. It is no accident that some of these new photographers who themselves situated themselves halfway between the fine arts and the mechanical arts came from the atelier of the painter who reportedly declared “From today, painting is dead!” when the invention of photography was announced. Whether or not Paul Delaroche (1797-1856) actually made that excited utterance is probably not as important as his support of Jacques Louis Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851) and his new process. Despite his fame and popularity with the public, Delaroche had placed himself outside of the Academy and refused to show in Salons due to increasing critical hostility to his work. His juste milieu popular but outsider status may have made him amenable to a mechanical process to recording nature, a process that aroused the ire and suspicion of some artists. In 1839 Delaroche wrote,

Mr. Daguerre’s process completely satisfies art’s every need, as the results prove. It carries some of its basic qualities to such perfection that it will become for even the most skillful painters a subject for observation and study. The drawings obtained by this means are at once remarkable for the perfection of details and for the richness and harmony of the whole. Nature is reproduced in them not only with truth, but with art. The correctness of line, the precision of form, is as complete as possible, and yet, at the same time, broad energetic modeling is to be found in them as well as a total impression equally rich in tone and in effect. The rules of aerial perspective are as scrupulously observed as those of linear perspective. Color is translated with so much truth that its absence is forgotten. The painter, therefore, will find this technique a rapid way of making collections of studies which he could otherwise obtain only with much time and trouble and, whatever his talents might be, in a far less perfect manner. When this technique becomes known, the publication of inexact views will no longer be tolerated, for it will then be very easy to obtain in a few instants the most precise image of any place at all. The engraver will not only have nothing to fear from the practice of this technique, but also he will come to multiply its results by means of his art. The studies which he will have to engrave will be of great interest to him. He will see with what art nature is rendered in them, and color interpreted. No doubt he will admire the inconceivably rich finish, which in no way interferes with the composure of the masses, nor does it at all impair the general effect. In conclusion, M. Daguerre’s wonderful discovery is an immense service rendered to art.

Delaroche’s paintings were theatrical in approach, a well-framed stage with action invariably centered, and narrative conveyed through readable gestures and postures. The drama of his favored historical scenes was tamped down by his glossy slick Ingres-like finish which froze the action in a stilled image frozen under varnish. Technically skilled and always entertaining, Delaroche was part of the French interest in the vanished past that characterized the Romantic movement. But there was always a high level of realism or historical accuracy in his work, which often examined the English history of ill-fated rulers.

Paul Delaroche. Lady Jane Gray (1834)

In order to do research for Lady Jane Gray (1834), Delaroche visited the Tower of London, which was also the site for his Princes in the Tower (1831). He viewed the site of Lady Jane Gray’s execution and had copies of Tudor furniture manufactured to enhance the authenticity of his setting. Most interestingly, as the son-in-law to landscape painter Horace Vernet (1789-1863), Delaroche was related to painting royalty, the Vernet family. Vernet was the son of artist Joseph Vernet (1714-1789) and father and son both favored dramatic paintings that were far more active than anything Delaroche produced. In his pairing of history and everyday life, Delaroche preferred the stilled and the paused over the diagonal and the active, presenting historical dramas in terms of the emotions of human beings who had lived, breathed and suffered. Regardless of their approaches the entire extended artistic family was deeply immersed in history, part of the prevailing Romantic mood of the time, a reaction against the encroachment of the industrialized present.

The Mission Héliographique coincided with the important seventeen volume (or nineteen, depending upon which source you read) Historie de France by Jules Michelet (1798-1874), who was forced into political retreat during the monarchy of the “citizen king,” Louis Philippe. It was Michelet who coined the term “renaissance,” referring to the sixteenth “discovery of the world and of man,” but it was the Medieval period that came alive in his pages. Although Michelet was considered too radical to ever be in favor no matter which regime was in power, he created a biography of the French nation and spurred the interest in the history of a country as a way to define nationhood.

The Multi-Volume Historie de France by Jules Michelet

Indeed, Delaroche’s students were part of the historicized generation that matured within the Second Empire, an intolerant period that tolerated Realism for the sake of conveying visual reality but not portraying social reality. The regime was censorious and the Salons were brutally biased against anything new, but there was something new and safely politically neutral in the air, landscape painting, which could be a safe retreat for any politically wary artist. Photography also offered another avenue for artists who were alert to alternative means of making art, and by the 1850s the simple salt print offered new possibilities for expression. And as the successful career of a politically marginalized Michelet proved, history could also provide a useful retreat free of contemporary controversy, and the new Emperor, Napoléon III, supported any venture that could delineate the patrimony of France.

The students of Delaroche would have been aware of their teacher’s interest in photography and it would be no surprise that two of them, Gustave Le Gray (1820-1884) and Henri Le Secq (1818-1882), trained and accomplished painters, were invited to join the (photographic) Mission Héliographique in 1851. The other members of the team included Hippolyte Bayard (1801-1887), one of the actual inventors of photography, Édouard Baldus (1839-1889) and Auguste Mestral (1812-1884), who worked with Le Gray. As a long term practitioner of paper photography and an experienced photographer, the senior Bayard would have also been an obvious choice, but the selections of Baldus and Mestral were somewhat unexpected. Indeed, Mestral was so unknown in the twentieth century that he was often referred to as “O. Mestral,”although the letter “O” had no known connection to his actual names. However more recent information has come forward, indicating that he was one of the founding members of the Société Heliographique, which explains his appointment to the group. After a lack of success in the Salons, Prussian-born Baldus had given up painting and had taken up paper photography. By the late 1840s Baldus had became a well-known architectural photographer, a new field, and a founding member of the Société. Both Mestral and Baldus continued their careers as photographers of architectural sites within the confines of the Mission and also worked on other independent projects, with Baldus rising to greater prominence and Mestral sliding slowing into historical oblivion.

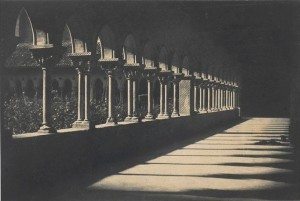

Perhaps the most prominent member of the Mission was Gustave Le Gray who was accompanied by Mestral. Le Gray began as a painter who took up photography, became a leader in photographic societies as a founding member of the Société Héliographique, and was a member and officer of the Société Française de Photographie. Of great importance to the Mission, Le Gray had developed a new process of preparing paper to receive the image. As early as 1849, he pioneered in coating his papers with paraffin and then switched to a new process which utilized dry wax in 1852, resulting in an image rich in detail. The waxed paper was highly suitable for the photography of architecture, particularly in regards to its details. Sadly, because the remarkable archive was, for some reason as yet unclear, simply filed and neglected for nearly a century, the work he and Mestral did in the Loire Valley are among the most difficult bodies of images to locate. Sometimes the work is attributed individually and sometimes dually. One of the most enigmatic images usually attributed to le Gray of a cloister of the church of Saint Pierre in Moissac.

Gustave Le Gray, St Pierre Church, cloister, Moissac, France (1851)

The photograph of the cloister is typical of the work of the Mission because it combined architectural detail, historical fact with a atmospheric mood redolent of the passage of time through a fabled place. Although the corridor is filled with sunlight, the deep shadows lend an air of mystery that is suddenly and inexplicably interrupted by a quotidian detail. Caught in the frame–meaning that the act is deliberate–near the central horizontal is a pile of what appears to be clothing, a discarded jacket or scarf and an upturned hat, perhaps. The image is beautiful and possesses that “punctum” that Roland Barthes would speak of a hundred years later in Camera Lucida–that odd pile of modern clothing discarded in a Medieval cloister shrouded in silence, leaving behind a question–the punctum that arrests the gaze.

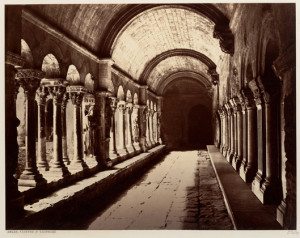

Just how remarkable this cloister image was can be seen when compared a cloister photographed by Édouard Balbus who was clearly interesting in giving as much information as light and angle would allow. The time of day he selected allowed the maximum light to flood the difficult to photograph corridor. The cloister is viewed almost straight on and there are no extraneous discards on the floor. Setting up these photographs was a precise and time consuming process. There was no such thing as casual or unplanned at this stage of photography; everything was deliberate. Baldus was an experienced photographer who had already learned how to do architecture. All of his work has the same straight-forward Dragnet–“just the facts ma’m”–perspective. No moods or atmosphere, just the information the government needed for classification, cataloguing and categorization with the object itself, the colonnade, strongly centered and clearly demarcated.

Édouard Baldus. Arles, Cloitre St. Trophime [Cloister of Saint-Trophîme, Arles (1861)

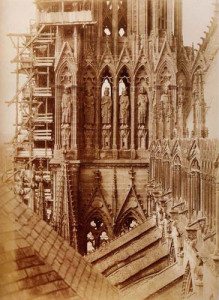

In examining the work of each photographer, the different styles become clear. Le Gray and Mestral approached their buildings with a formal appreciation for composition, strong arrangements of darks and lights and an appreciation for strong silhouettes. Édouard Baldus produced images that were carefully framed and elegantly composed. Henri le Secq was the master of minutiae. Le Secq showed an interest in capturing the intricate details of cathedrals, meaning that, in order to make sure that the maximum amount of information was gained, the light had to be precisely right. No shadows, just the architectural forms enveloped in the strong glare of the sun. It is interesting to note that le Secq was trained as painter and as a sculptor and was an expert in Medieval ironwork, interests that are revealed in his work for the Mission. The tower of the Kings at Reims Cathedral shows the building already under restoration, and le Secq was perched on the roof showing to future viewers a vantage point denied to most pilgrims. In showing the Kings standing tall their niches, towering above the ground, le Secq was not only revealing structural details of Gothic architecture but also the mindset of the Medieval artisan. Because the Cathedral was dedicated to God, the outpouring of care in a place to be seen by humans only from afar (a God’s view from heaven) was a spiritual act by workers who believed that their creator would approve of their efforts.

Henri le Secq. The Tower of the Kings. Reims Cathedral

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.