New Topographics

The New West, Part One

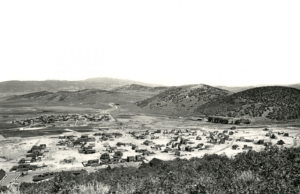

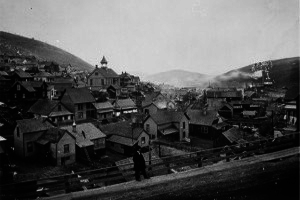

Park City, Utah was always a bit of an oxymoron. Not a park, the “city” was a mining town with all the attendant hardscrabble buildings that marked the place where mine shafts probed be depths of the earth searching for silver. By the 1870s, the Park City Mining District presided over the Ontario Mine, which for a time was the greatest silver mine in the world. But mining is a dangerous business and the mountains of Utah were inhospitable and Park City became the place where disasters happened. In June 1898 a huge fire, driven by high winds, swept through the town, consuming three-quarters of the flimsy wooden structures. According to the “The History of Park City, ” “The blaze was the greatest in Utah history.” The terrible fire was followed a few years later in 1902 by the worst mining disaster which killed thirty-four men in an explosion of dynamite stored underground. In the early twentieth century, winter sports were another oxymoron, for skiing was a necessary means of transportation and not a leisure activity. However, as early as 1906 two skiers showed up but their appearance seems to have made little impact at the time. But someone apparently noticed that the hills of Park City could be used for more than silver and in 1931 a record ski jump took place on Ecker Hill which had been expressly built for the purpose. The jumper Alf Engen soared some 247 feet and landed safely. In 1936, skiing had become an actual sport and Park City launched a Winter Carnival that attracted hundreds of skiers. And then the Second World War intervened and the mining industry became untenable. By the early fifties, Park City had become a “ghost town,” nearly abandoned. The mining company realized it owned valuable real estate and over the next twenty years resurrected Park City as a ski resort. The process involved wiping out a rather raucous history of a mining town and its red light district and replacing the past with a more upscale present.

Park City, Utah before renewal

It could not be argued that Park City was in any denigrated by the transformation but when Lewis Baltz turned his camera towards to renewal process he did so with a disinterested eye. “I hope that these photographs are sterile, that there’s no emotional content,” Baltz said. There are parallels between the development of the Irvine Ranch and the redevelopment of Park City with both areas being presented to the well to do who enjoyed a carefully cultivated if somewhat artificial landscape. One could look for a moral center that would underpin a critique of an exploitation of natural resources but Baltz deliberately refused any hints of an environmental complaint. Historian Susan West described the approach of the New Topographics photographers as an “anthropological style,” that is the observation of the detached scientist who studies an object/subject without judgment. In his 2010 discussion of the exhibition in 1975, Britt Salvesen wrote that “..we can see New Topographics as a bridge between the still-insular fine-art photography world and the expanding, post-conceptual field of contemporary art, simultaneously asserting and deconstructing the medium’s modernist specificity, authority, and autonomy.” Salvesen made an additional point to West’s anthropological assessment by noting that (as with the Bechers) the photographers had no aesthetic intent. Indeed, one would never characterize the photographs of Park City as “beautiful.” Taken in the offseason, a time without snow, during the transition period from the mining town to a ski resort, these images faithfully reproduce the upheavals of the earth, the mounds of dirt, the piles of ground, none of which is the least bit picturesque or even particularly interesting. Baltz refused to cater to the spectator’s expectation of “landscape” and its eighteenth-century categories.

Writing for The Los Angeles Times, Leah Ollman said that the Park City series was, “Relatively dry and factual yet interesting, the images read as an essay that argues implicitly against the aesthetic and environmental offenses committed during Park City’s development boom of the late ’70s. Baltz starts out pairing distant mountain ranges with nearer heaps of rubble and debris from new housing construction and the area’s former function as a mining dump.” In her 2012 catalog on Lewis Baltz, Susanne Figner used the term “technological sublime” to account for the nihilism seen by other writers. West contended that the merit of the Park City series lay not in the subject matter but in the area where Gus Blaisdell found it: “Baltz’s talent in the darkroom, and keen understanding of technical and chemical processes that work exceptionally well for his images. The composition of the photographs also demonstrates his honed artistic eye for organizing shapes and balancing content within the frame, embedding a lively rhythm within the picture.” Baltz himself described his work in terms of space and time: “To work in a way integrated with architecture, I think the work we’re speaking about here is not a question of putting my work in his building but a question of using that building and the activities in that building as a way of generating a dialogue in images. The work is not even site-specific, it’s really site-generated. It’s something that’s made exclusively for that space and that space with its present series of functions. In that sense, it becomes like most works today ephemeral.”

For Baltz, the 1979 Park City project was part of a trilogy, starting with the urban/suburban landscapes in Irvine and concluding four years later with the San Quentin Point, the site of a dump where one of California’s most notorious prisons presides. As a name, San Quentin is a bit of a misnomer as the “san” is an add-on to a proper name of an early prisoner of the young state, “Quentin,” a Licatuit Indian warrior. Today the huge prison, crumbling and baleful and famed for its brutal history is the only facility in California equipped to carry out executions. For those who watch the price of real estate, San Quentin point in Marin County is valuable land but closing the prison is currently impossible and the dream of developing this tantalizing plot of land floats just out of reach. When Baltz photographed the Point, it seemed to follow a project that witnessed a building of something new, a development of land that updated its use. The Point and its blighted land, found by the photographer, seems to tell a different story, one of intractability. Used for “the disposal of non-hazardous solid wastes such as construction and yard debris,” the “landfill” that was explored by Baltz was closed in 1987. The government report continued with optimism: “Following closure in 1987, the landfill was divided into multiple parcels for future land development. In 1996 and 1999, two buildings were constructed within the refuse limits of the former landfill, the Home Depot and the Benjamin Building, respectively. Furthermore, in 1999 BMW completed construction of a car dealership directly adjacent and southwest of the former landfill.”

Lewis Baltz. San Quentin Point (1984)

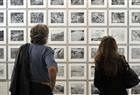

If anything could be more depressing than a prison, then it would be a dump and the blanching out of the images in this 1983 series stresses the awful sadness of this site. When shown, the San Quentin images are jostled together as a gridded group marching mercilessly up and down the gallery wall as shown recently at the Basel Art Fair. The grid, seen below, also practiced by the Bechers, serves to organize and group a class of images, but, in the case of Baltz, the grid is also the way in which the West was carved up and parceled out and then passed around to those who would occupy it. The precision of the dismemberment is the mark of the way in which the West was disposed of. The “East” grew organically and the ownership and use of the various plots of land were established over decades, even centuries. However, the “West” created suddenly, over a very short period of time. Vast stretches of the territory were flat and expansive, lending itself to the grid layout that can be experienced in the way in which the great ranchos were parceled up, the manner in which the cities were laid out, the method used to plan developments for the suburbs. The irony of the grid is that it lies like a net at the base of high mountain ranges, trapping the once open land, tying it down, in a rebuke to its former wildness.

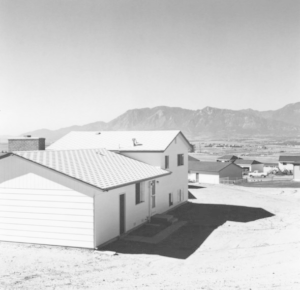

So the New West is not so wild anymore. This disconcerting lack of center of interest is echoed in the work of Robert Adams (1937-), which is also a non-“landscape” landscape, that is, un/pictures/que, raising the question of why was this ordinary place photographed at all? As John Szarkowski, stated in his introduction to The New West (1974) by the photographer, “Adam’s pictures are so civilized, temperate, and exact, eschewing hyperbole, theatrical gestures, moral postures, and espressivo effects generally, that some viewers might find them dull.” In his discussion of this seminal text, Daniel Shea noted that “..The New West famously depicts the tract houses, highways, and business developments along the Colorado Rocky Mountain. Aperture’s facsimile reissue is absolutely stunning, each plate effectively replicating the full tonal range of the original black and white print. But the book’s dust jacket implies a simplistic and deadpan (both physical and emotional) look at America’s latest ugly housing phenomenon when in reality, there is more than enough of Adam’s personal vision and departure from the topographic nature of the work.” Like Lewis Baltz, Adams grew up in a place that was once open and relatively unoccupied. His family moved to Colorado from New Jersey when he was twelve, shortly after the Second World War, when the West would become, once again, a place where Americans turned to renew after a long and bloody war. Like Baltz, he would have been a witness to the change from open land to land gridded and divided and sold off. Adams begins at a slightly different place from Baltz, as he seems to organize his images into a sequence: from available land studded with signs offering what seems flat and bleak to those driving across the state. Then Adams finds the new settlements, the new pioneers in their new towns, cordoned off into neat and tidy streets.

Robert Adams. The New West (1974)

Robert Adams. The New West (1974)

Although these images—only a year old–were featured in the New Topographics exhibition in Rochester and are thus conveniently classified as being “objective,” the vision of Adams is one of moral approbation. He attended the University of Redlands in California, a place of great beauty and charm. The town of Redlands abounds with Victorian homes, now carefully preserved for their unique interpretation of one of the great architectural styles of the fin-de-siècle West. In contrast, the Colorado desert extending beyond the foothills lacked this picturesque quality. And yet these open lands, in their untouched state, once carried memories of the frontier and all of its possibilities. Gridding closes off opportunity, dictating what the land can be “used” for. But what have we done to the land? In The New West, Adams wrote, “Though the mountains are no longer wild, they still dwarf us and thereby give us the courage to look at our mistakes – expressways, Tyrolean villages, and jeep roads. Such things shame us, but they cannot outlast the rock; in sunlight, they are, even for a moment, like trees.” But his lament can be echoed through the ages: in Europe, the old primeval forests were stripped away to build the scaffolding for the cathedral vaults, and when the descendants of the cathedral builders arrived in America, they systematically chopped their way across the frontier. Nor is this predatory behavior unique to Europeans. In Brazil, the inhabitants burn the rainforest, putting the entire climate in peril. But the hunger for land seems to be one of the driving forces, if not of civilization, at least of human behavior.

The next segment will discuss The New West by Robert Adams.