New Topographics

The New West, Part Two

The New Topographics movement in America was an attempt to be “objective” about its survey of the West in post-war America. Writing in relation to The New West, the 1974 book of photographs of the developing of the Denver suburbs, Lewis Baltz defined what was meant by “topographics” or the “topographic:” “There is something paradoxical in the way that documentary photographs interact with our notions of reality. To function at all as documents they must first persuade us that they describe their subject accurately and objectively. In fact, their initial task is to convince their audience that they truly are documents and that the photographer has exercised his powers of observation and description rather than his imaginings and prejudices. The Ideal photographic document would appear to be without author or art.”

The statement by Baltz, who, like Robert Adams (1937-) wrote extensively about photography, is interesting because he wanted to return to the initial or founding use of the camera in that what it produced would be a record, a document made by a mechanical device. The photographer was or is merely the human who is instrumental in pushing a button. But the “powers of observation and description” were key in that these terms imply discretion and choice on the part of the photographer who is the observer and is the one who points the eye of the camera, guiding the lens to a particular location which will be framed for capture. Supposedly, the new topographics photographer would eliminate the imagination and personal prejudice, but, when the various artists in the movement are examined, it is clear that each has an individual approach that is distinct and identifiable. Frank Gohlke, for example, would photograph his sites from extreme distances. In fact, Gohlke is usually so detached from the landscapes that when he frames a close-up so to speak, it is a shock to the eye. Much of his frame would be habitually taken up by emptiness and negative space which would become the compositional dominant overtaking the supposed focal point. Likewise, it is impossible to confuse Lewis Baltz with his colleague Robert Adams. Baltz seemed attracted to places in transition, existing for a few weeks in a liminal space and fluid time: today the land is like “this,” tomorrow it will be “that” but we never see the outcome and the land is frozen in process.

Adams, in contrast, was more interested in the outcome. Outcomes fill his frames. While some might wince at the depressing results, the photographer remarked that “all land, no matter what has happened to it, has over it a grace, an absolutely persistent beauty.” But is this beauty a memory of a distant past or an acceptance of a new definition of “beauty” in an age of conformity? As discussed in earlier posts, the New Topographic movement was, for the most part, concentrated in the modern West, not the East, but the frontier territory, a legendary locale of lore now relegated to pulp fiction and old movies. The West as the new Garden of Eden or the refuge of those on the run to their next lives has a unique role in American history. On one hand, the government and corporations and the military teamed up to conquer, subdue, settle and develop land considered “virgin.” This land was either given away or at very low prices to those willing to “civilize’ it and the Army was deployed to sweep the original inhabitants in to “reservations” or land “reserved” for them. But, on the other hand, Manifest Destiny had its cost and the price was the loss of the dream of renewal. No longer was the West a goal that beckoned to those who needed redemption.

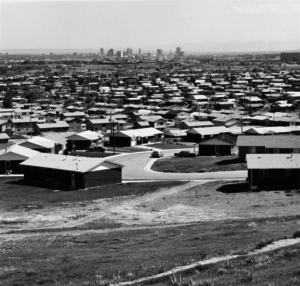

By the end of the twentieth century, it was left-over land, land to be developed a hundred years after the original invasions, or it was set aside land, worthless land to be used by the government for its weapons testing. The task of Robert Adams was to observe the benign and banal suburbanization of The New West. In his 1974 book, the photographer shows emptiness that then fills. Homes, from trailers to suburban boxes are moved to a grid into contemporary settlements that are consequently given a name, transforming empty space into a filled place. Overlaying the web of streets lined with one story ranch-style homes is a feeling of nostalgia and a sense of history as a backdrop, framing the images of the untouched stretches of desert and mountain lands, photographed by Timothy O’Sullivan and Willliam Henry Jackson. In 2010 the Los Angeles County Museum of Art restaged the original 1975 exhibition, and, looking back almost forty years later, it seemed clear that the work of these artists was symptomatic of a coming wave of altering the landscape. As writer Christy Lange noted for Frieze, “It’s remarkable to see how presciently ‘New Topographics’ captured the alarming, burgeoning aspects of American land use that would soon become endemic throughout the nation, calling for sociological concern not just aesthetic attention.” In point of fact, The New West is cataloged in libraries under, not art, but sociology.

Robert Adams. Mobile Homes, Jefferson County, Colorado (1973)

it is the collective memory of the “Wild West” that empowers The New West. Although the name of Ed Ruscha and his many small books, such as the 1963 work, Twentysix Gasoline Stations, is often evoked in relation to the New Topographics group of photographers, his work is not cast against the backdrop of Western “scenery” or of landscape painting. Ruscha’s gas stations were about the road, about traveling, about the journey along route 66 between the Midwest and Los Angeles, a migratory route. Turning the pages from station to station does not involve a vague mourning, but rather a sense of the familiar needs of the driver before the time of freeways. In addition, the name of Walker Evans is also often brought forward as a precursor of New Topographics, but only rarely do we see the flat and truncated approach of the early photographer. It should be pointed out that it is far more apt to use Evans in relation to Robert Frank. Both were strangers in a strange land. Evans was a northeasterner, roaming the unfamiliar South, regarding this alien region with the eye of the curious foreigner, seen twenty years later in Frank’s The Americans. Evans, who preferred strongly structured close-ups, used the faces of buildings, often covered with text, signs, lettering, and other forms of messaging, as an almost abstract composition by Mondrian. The New Topographics artists seek open space and study how it is covered up. What they are gazing upon is the built environment, acts of architecture; what Evan photographed with his closely framed straight-arrow view camera was semiotics.

Robert Adams. The New West (1974)

Like Lewis Baltz, Robert Adams reviewed the place where he grew up. Like Irvine Ranch, the foothills and deserts at the bottom of the mountain ranges near Denver had been left alone, testaments to the openness of the West. But, the demands of the post-war for places to grow and expand, necessitating places to live, changed the flat blank desert land into strip malls, shopping centers, parking lots, square lots for rectangular homes. As Adams wrote, “..the area’s ruin would be a testament to a bargain we had tried to strike. The pictures record what we purchased, what we paid, and what we could not buy. They document a separation from ourselves and, in turn, from the natural world that we professed to love.” Adams was perhaps referring to the love of the natives of the West for the “big sky,” the totally open unobstructed landscape. This was land from which one could look up and see the stars, now the available light overwhelms the natural dark and light of the heavens. In a later book, Beauty in Photography (1981), Adams said of landscape and its role in the American unconscious: ”We rely, I think, on landscape photography to make intelligible to us what we already know. It is the fitness of a landscape to one’s experience of life’s condition and possibilities that finally makes a scene important or not.”

Robert Adams. The New West (1974)

The New West is laid out as a narrative journey. The book begins with a flat and otherwise nondescript view from the side of an empty road, flanked by a lone telephone, supporting two wires. Clearly, this is settled land–the telephone must connect with someone. The shadow of a tree points its triangular shape into the right side of the frame and is echoed by the wedge of leaves pushing into the top right corner. The the next image picks up another dual telephone wire, asserting itself over an otherwise untouched landscape of hills, rolling slightly. A horizontal row of trees peeks above the crest of the closest rise as if watching the viewer approach. The third photograph is a preview of the forth. A lonely low rusted sign, its purpose obliterated by wind and weather, punctures the hard dry ground. Far beyond in the dim distance, a torn edge of a mountain range ends the apparently endless and unmarked terrain. The fourth image is all about real estate. The sign marks the desert, announcing that it is owned and will be sold. This is “frontage” property, the sign asserts as an elaborate tiered telephone pole, with five crossbars, promises connection with the outside world. The fifth photograph is a dead rabbit, a warning that is both stark and ambivalent. The rest of the book marches the reader out of the empty desert into the suburbs, made of mobile homes and packed developments that are perhaps “towns.” From these fringes, the houses become more “mature,” indicating that they have been built earlier than those at the far edge. Then comes the city, the heart of and the inspiration for the expansion of the settlements. The city supports the outlying neighborhoods and the inhabitants support the city. The relationship is reciprocal, inspiring the erection of small skyscrapers and a variety of drive-in services. Suddenly The New West veers back to the desert edges, what is left over, perhaps awaiting further development. And beyond, as the book comes to an end, lie the mountains, that which may or may not be impervious to the blandishments of developers.

Robert Adams. The New West (1974)

In an apparently bleak mood, Robert Adams wrote, “When we are young we want art that is filled with the bitter facts because we believe that evil can be overcome if we face it, When we grow older and begin to doubt this optimistic belief we want an art that does not simply reinforce our disillusionment.” Adams presided over an increasing dark view of the world that characterized the 1970s and 1980s, decades that witnessed nascent efforts to protect the landscape–that which was left–and deliberate destruction of nature. As a photographer of the West, Adams was walking not in the footsteps of earlier photographers but in the underlying traces of the raison d’être of “landscape:” nature and beauty. In his book, Art Can Help (1984), he wrote sadly, “Until fairly recently, the word art applied to pictures usually referred not just to representations of the world but to representations that suggested an importance greater than we might otherwise have assumed. Such pictures were said to instruct and delight, which they did by their wholeness and richness. The effect was to reinforce the meaning of life, though not necessarily a belief in a particular ideology or religion, and, in this, they were a binding cultural achievement. Unfortunately, art of this quality is now little attempted, partly because of disillusionment from a century of war, partly because of sometimes misplaced faith in the communicative and staying powers of total abstraction, and partly because of the ease with which lesser work can be made and sold. This atrophying away of the genuine article is a misfortune because in an age of nuclear weapons and overpopulation and global warming we need more than ever what art used to provide.”