A Fair at the Edge of Time

The Futurama of Norman Bel Geddes

In the early decades of the twenty-first century, when women speak out and say “Me Too,” one has grown accustomed to the time-honored art historical practice of ignoring the bad behavior of male artists and look only at the art. But every now and then, the attitudes of men–typical of their time–give one pause. It is probably not well known, but the great designer Norman Bel Geddes designed a show for topless dancers at the New York World’s Fair of 1939. The operative word was probably “Fair,” which meant to the American mind “amusement.” In Chicago in 1933, one of the main attractions was the famous fan dancer Sally Rand. In contrast to the expositions in France where the emphasis was upon the arts, Americans were more interested in spectacle, and one of the expected spectacles was nude or nearly nude women in “girly shows.” According to the Archives & Manuscripts for the New York World’s Fair,

“The amusement zone drew visitors to the Fair as well and helped the corporation to earn additional income through admission fees charged by selected concessionaires, a percentage of which was paid out to the Fair. Billy Rose’s Aquacade was the undisputed hit of the amusement zone. This water show, which featured Olympic champions Eleanor Holm and Johnny Weissmuller and a cast (according to promotional literature) of “fetching mermaids and virile mermen,” earned Rose an estimated five million dollars. Although Whalen had early on promised that the Fair would be free of “fan dancing” or lewd “girlie shows,” the potential loss of lucrative attractions produced a more lenient position towards entertainments featuring nudity and exotic dancing. While this altered stance generated controversy, burlesque shows helped rent space in the amusement zone and brought in paying visitors craving something other than culture and education. Salvador Dali’s Dream of Venus, Norman Bel Geddes’ Crystal Lassies and the Cavalcade of Centaurs — featuring scantily clad or naked women in tanks of water, refracted in mirrors or bare-breasted on horseback — were among the attractions that drew criticism and crowds.”

One might think that a self-respecting designer would not participate in a striptease show but these attractions were profitable and apparently in the 1930s the word “objectification” had yet to be uttered. The event was described by the New York Post as a “polyscopic paradise for peeping Toms” where men with scopophilia could watch the “Cyrstal Lassies.” The headline for the Post article read, “Norman Bel Geddes Gets Very Boyish Idea Seeing Dream Reflected in Mirrors.” The “dream” in question was that of a scantily clad woman infinitely reflected in a mirrored room. Only one woman was on display at a time, but she was multiplied in an octagon room. As the Bel Geddes Database explained, “..there were a total of 32 surfaces. In total, approximately 100 pieces of glass were used, mostly 1/4 inch glass with a mirrored back. Around the circumference of the room ran three 4 ft wide strips of 1/2 inch thick one-way or “speakeasy” glass at 8 foot high intervals. This “speakeasy glass” was mirrored inside the octagon but clear on the gallery side, allowing spectators to look through into the mirrored room without being seen themselves, and unable to see other spectators. Maximum capacity was around 600 people, and each show ran approximately 12 minutes..”

Originally, the women who performed were supposed to be topless, but there were some complaints about propriety and the order came down to cover the tops. To the horror or Bel Geddes who preferred naturalism, the women were forced to wear bras. The designer found the underwear “vulgar” and the women were allowed to go topless again. According to Alexandra Szerlip in The Man Who Designed the Future: Norman Bel Geddes and the Invention of Twentieth-Century America, “Spectator anonymity was a priority. As many as 600 visitors at a time would stand on “peeping platforms” on three levels provided with window slits. Thanks to carefully arranged strips of one-way mirror (also known as Chinese or “speakeasy” glass), each would have the illusion of being the sole onlooker, and dancers would be unable to observe their observers once the lights came up..Dressed in a harem outfit—a G-string, a gauzy chiffon skirt, the occasional veil—each girl danced for three minutes before being replaced by one of eight colleagues.” Financed by fifteen men, the Crystal Lassies opened in 1939 and closed in 1940 with cocktail parties, hosted by Bel Geddes, who apparently did not find striptease shows, inspired by speakeasies, to be “vulgar.” Given that the main accomplishment by Bel Geddes was to imagine the world of the future in 1960, it shows a true failure of the imagination to think that women would be eternally topless and In a state of perpetual gyration for the pleasure of peeping toms. But in 1939, as one man said, “What it was really all about was naked ladies. You couldn’t have a world’s fair without ’em. Everybody knew that.” American fairs had long been marred by the events that were supposed to entertain–after all, it was too much to expect the public to spend all day becoming educated. The genesis of the World’s Fair in New York was, in its own way, a bit of a miracle of technological thinking and urban renewal.

It was unfortunate that the New York World’s Fair of 1939 opened in 1939. Flushing Meadow, newly reclaimed from a landfill, became for two brief years a site of retreat from the present and a visit to the future, allowing Americans an escape from a world that was moving once more into its war positions. The site was well known to the readers of F. Scott Fitzgerald, who used the ash dump as a place of foreboding in The Great Gatsby. “About half way between West Egg and New York, the motor road hastily joins the railroad and runs beside it for a quarter of a mile, so as to shrink away from a certain desolate area of land. This is a valley of ashes–a fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat into ridges and hills and grotesque gardens; where ashes take the forms of houses and chimneys and rising smoke and, finally, with a transcendent effort, of men who move dimly and already crumbling through the powdery air. Occasionally, a line of gray cars crawls along an invisible track, gives out a ghastly creak, and comes to rest, and immediately the ash-gray men swarm up with leaden spades and stir up an impenetrable cloud, which screens their obscure operations from your sight.”

Some eighty years ago, this Fair, in retrospect, was nothing short of a refusal to accept the facts of the present, ignore the events in Europe–the rise of Adolf Hitler, the menace of Benito Mussolini, the betrayal of Stalin and the utter futility of Chamberlain’s appeasement policy towards Germany and present “Building the World of Tomorrow” to America. Feeling safe and secure behind thousands of miles of oceans flanking its sides, America or the city of New York decided to provide hope to a Depression-weary nation–there would be an end to the economic struggles and a better future was a mere two or three decades away. The Fair, predominantly colored in white, literally rose from the ashes, thanks to Robert Moses, whose vision for New York included parklands and places for the automobile, was inspired by the opportunity to turn an ash pit into useful land. As he wrote later, “..the accumulated clinkers, dust, offscourings, waste, and junk of hundreds of thousands of Brooklyn families had their monument in this horrendous mountain..By the greatest stroke of luck, the progenitors of the World’s Fair came along at just this time and asked me to go into partnership with them in the location of the Fair in the Flushing Meadows. Nothing could have been more opportune.”

Moses had great plans for the Meadows after the Fair, but after 1940, the nation went to war and his plans were put on hold until another World’s Fair in 1964 and the site which today includes the National Tennis Center and the New York Mets stadium and other buildings from the Fair, now museums. But in 1939, the World’s Fair was more compact, centered around two shapes, the seven hundred foot Trylon and the Perisphere with a two hundred foot circumference. Lest one think that these two structures were mere ornaments, as the Daily News of 1939 wrote, “Inside the 18-story Perisphere, in an auditorium the size of Radio City Music Hall, thousands rode on two moving balconies and looked down on Democracy, a mammoth model of the city of tomorrow — a city of broad streets, many parks, and large buildings.” The two abstract geometric shapes were blindingly white, speaking loudly of a future that had risen in perfect and pure forms out of a smoldering valley of the ashes. What could be more fitting? The Future generated by the discarded past.

Celebrating the 150th anniversary of the first inauguration when George Washington took the oath of office in New York City, the Fair celebrated not just the future but commemorated the past. The first president, the Father of his country stood in front of one of the many lagoons, framed by the periscope behind him and flanked by statues of nude males and females–allegorical figures–the “Four Freedoms” by Leo Friedlander. If the President recovered from the surprise of finding himself in such company, he might have been able to gaze upon the National Cash Register building, topped by a huge cash register, designed by one of the competitors of Bel Geddes, Walter Dorwin Teague. The world’s largest cash register revolved and displayed the attendance numbers for each day. Inside the building, the visitor could view all of the seven thousand eight hundred fifty-seven parts of an actual cash register. The Wonder Bread building, where one could watch the process of making and baking the most famous white bread in the nation and witness the birth of Hostess Cakes, was “wrapped” in a reproduction of the iconic colored poker dotted cover. In contrast to the corporate buildings, the national pavilions tended to be more modest or at least less entertaining works of architecture. The Coca-Cola Building had a one hundred twenty foot spire or carillon with six hundred ten bells that struck the hours of the Fair. Inside one visited the “world of refreshment” including a Hong Kong street, an Indian garden, a Bavarian ski lodge, a Cambodian forest and a view of the harbor of Rio de Janerio.

But the Soviet Pavilion made its presence known with what was described by Anthony Swift as “The stripped-classical structure formed a semi-circular columned courtyard, in the middle of which stood a 180-foot pylon that supported a 79-foot statue of a worker holding aloft a red star.” Unlike the 1937 World’s Fair when the Soviet Pavilion confronted and rivaled the German Pavilion, Communism staring at Fascism, the Russians had come alone. The Soviet Union, having signed a non-aggression pact with aggressive Nazi Germany participated with a pavilion that was decidedly retrograde compared to the Konstantin Mel’nikov’s architecture at the World’s Fair in Paris in 1925. Germany, busily invading Poland declined to attend but Poland draped its pavilion in black when the Nazis took over the small nation. Designed by Boris Iofan in collaboration with Karo Alabian, the Pavilion celebrated Stalin in what was largely a reprise of the 1937 building. Inside a huge mural depicted the gradual modernization of the vast territory under Communist rule, topped by words from Stalin: “We have now a fully-fledged multinational socialist state which has stood all the tests and the stability of which might well be envied by any national state in any part of the world.”

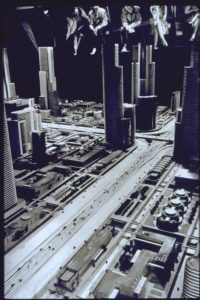

The most popular building and the most popular exhibit was the General Motors Building where one would stand in line for hours to experience the “Futurama” designed by Norman Bel Geddes. Once inside the building, which was often wrapped around twice by patient lines of hundreds of patient people, one would be treated to “magic Aladdin-like flight through time and space,” or so said the New York Public Library, quoting the opening lines of the Futurama: “Come tour the future with General Motors! A transcontinental flight over America in 1960! What will we see? What changes will transpire? This magic Aladdin-like flight through time and space is Norman Bel Geddes’ conception of the many wonders that may develop in the not-to-distant future.” The spectators sat in three hundred twenty-two “carry-go-round” seats that tilted forward to allow them a view of a panoramic construction, measuring 35,738 square feet, of the City of Tomorrow called “Highways and Horizons.” The idea for the City came from his campaign for the Shell Oil Company in 1937 also called “City of Tomorrow,” but his early promise was based upon the gift of gasoline and the better way of life it would bring. Spread out beneath the dangling feet of the fair visitor was a vast miniature landscape that was explained by a male voice droning in the ears of each visitor. The rather prime and deep male voice, pausing between phrases, described the vistas as the chair-cars revolved around the room. What seems to us today as a boring recitation was actually, in 1939, a technological marvel. The machine made sure that each visitor, no matter where he or she was on the conveyor belt would receive a perfectly synchronized description of exactly what was being presented at that very moment. By the time the Fair closed, the recording had been heard over five million times and never was a mistake made.

The world created by Bel Geddes was the equivalent of a huge model blown up to a very large scale and containing come 500,000 buildings, over a million trees and at least 50,000 motor vehicles. These cars, mounted on tracks, “drove” down the streets and highways, looking like orderly ants, at least from the vantage point of the swirling chairs.The city of 1960 was spread out before the astonished eyes of citizens of the 1930s. Listening to “To New Horizons,” the visitor imagined herself in an automobile touring the outskirts of this future city, planned for the automobile which would speed along tear dropped shaped curving highways that linked the urban and suburban areas. Elevated walkways gave pedestrians another means of journeying through the city streets by moving between buildings. As the carry go round cars raised and lowered themselves, lifting the viewers to different vantage points, the city streets were, as one would expect for a General Motors building, full of cars.

The city of the future, like that of Le Corbusier in 1925, was built for moving the automobile from one point to another. Neither Bel Geddes or Le Corbusier could have imagined that congestion would be a problem that could never be solved nor did the designer realize that the freeways would not only connect city to country but allowed the motorists to bypass much of the city, thus missing its various pleasures. The buildings for the painstakingly realistic creation of the city of the future were designed by the architect Albert Kahn, who build tall thick skyscrapers that would be stacked full of people. But rather than being crowded in a small space, like Manhattan Island, the tall buildings spread out and rose separately, allowing ample space for lower buildings. In fact, the designers placed the city of the Future in the Midwest where the Dust Bowl still ravaged the land and one could build freely on the flat prairie expanses. The optimistic placing of the future of 1960 in the Midwest promised that the drought would be over and that the city of tomorrow would rise from the dust like the Fair from the valley of the ashes. Bel Geddes dropped his spectators into a journey that took them from the past and into the present and then to the future. Leaning forward in their comfortable chairs, viewers cruised over verdant rural pastures and then viewed the edges of the cities, coming into view, until the future arrived in the guise of gleaming glass buildings rising above a city designed for automobiles–something everyone would own in the future.

Bel Geddes dropped his spectators into a journey that took them from the past and into the present and then to the future. Leaning forward in their comfortable chairs, viewers cruised over verdant rural pastures and then viewed the edges of the cities, coming into view, until the future arrived in the guise of gleaming glass buildings rising above a city designed for automobiles–something everyone would own in the future. There was a seven-lane highway where drivers could achieve speeds of seventy-miles per hour–an Autoban experience. Bel Geddes designed “motorways” that overlapped one another, very much like today’s freeways, and imagined the drivers approaching the main roads on loops that were well graded enough to allow them to enter and exit at fifty miles per hour. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Californian freeways would achieve and surpass these designs–right on schedule. Industrial areas, old worn out and tired, would be replaced by parks; slums would be eliminated; all would be new and shiny and white and green. In the city of 1960, the inhabitants would live in a sterile city in glass towers that presided over gridded sections of lower buildings. These tall buildings were a quarter of a mile high and the rather new aircraft, the helicopter, could land on the roofs. Almost as interesting as what Bel Geddes include was what he excluded: public transportation and the suburbs. One went from the country to the city in a car, one drove around the city in a car. Of course, the sponsor was General Motors whose desire it was to sell everyone an automobile. Every element of this imaginary world was built by hand, lovingly crafted. Donald Albrecht, the curator of architecture and design at the Museum of the City of New York, described the future of Norman Bel Geddes as a “Disneyland” ideal, which of course was the point in Depression-ridden American. From the first day, people lined up for this exhibition, as if eager to escape the economic turmoil that seemed to have no end.

The visitors would, after a long wait, be transported into the future for fifteen minutes: fifteen minutes of escape into a world of hopes and dreams. Bel Geddes described his city, “Futurama is a large-scale model representing almost every type of terrain in America and illustrating how a motorway system may be laid down over the entire country-across mountains, over rivers and lakes, through cities and past towns-never deviating from a direct course and always adhering to the four basic principles of highway design: safety, comfort, speed, and economy.” The world created by Bel Geddes was the equivalent of a huge model blown up to a very large scale and containing come 500,000 buildings, over a million trees and at least 50,000 motor vehicles. Every element of this imaginary world was built by hand, lovingly crafted. Donald Albrecht, the curator of architecture and design at the Museum of the City of New York, described the future of Norman Bel Geddes as a “Disneyland” ideal, which of course was the point in Depression-ridden American. From the first day, people lined up for this exhibition, as if eager to escape the economic turmoil that seemed to have no end. As Albrecht said, “It was Geddes, more than any designer of his era, who created and promoted a dynamic vision of the future with an image that was streamlined, technocratic, and optimistic.” Bel Geddes imagined the city the same way he imagined his stage sets, a combination of sets, lighting, and emotion. The emotion is not just one of hope at a desolate time but a realizable dream based on recognizable and existing prototypes. In his book, Magic Motorways, explaining his dream city, the designer explained, “Peering through the haze of the present toward 1960 is a great adventure..In designing Futurama, we reproduced actual sections of the country–Wyoming, Pennsylvania, California, Missouri, New York, Idaho, Virginia–combining them into a continuous terrain. We used actual Amerian cities–St. Louis, Council Bluffs, Reading, New Bedford, Concord, Rutland, Omaha, Colorado Springs–projecting them twenty years ahead. And, of course, we took existing highways into account, making use of their most advanced features and, at the same time, projecting them also twenty years ahead..The Motorway System as visualized in the Futurama and described in this book has been arbitrarily dated ahead to 1960–twenty years from now. But it could be built today.”

Szerlip quoted the ecstatic press: “The model landscape strikes the armchair audience dumb with amazement and admiration,” applauded The New York Daily News. “Norman Bel Geddes built it in eight months, with 2,800 people helping him.” She noted that “the circuitous “carry-go-round” ride, marveling at its 1,586 feet..and the convex-concave “wishbone” coupling of its cars that allowed sharp twists and turns as it rose as much as twenty-three feet, and all without jerks, jolts, screeching, or skidding, carrying some 2,200 visitors per hour, 28,000 daily. Four months of mathematical figuring had been required to create this perfectly counterbalanced magic carpet.” It is interesting to view the Futurama ride in relation to the other glimpses of the future–the television set displayed at the fair—and the advent of Technicolor film. Both of these advances, like the glass cities would be halted by the Second World War. Only after four long years of war was it possible to turn from the task at hand to the idea of the future left behind by Norman Bel Geddes. Ironically, the visitors all left the exhibition and exited the General Motors Building wearing a blue and white pin “I have Seen the Future” it claimed. It was a future that would be along time coming.