Paul Nash (1889-1946)

Death Stalks the Artist

War is a very intense experience. For poets, war inspires a torrent of words tumbling out in anguish, for novelists, fiction provides a thin veil though which they can filter their fears and terrors. For artists the war is terrifying and fascinating–not in its glory,for there is none of that—but in its totality. War swallows everything: wipes away the life before and diminishes the life afterward. The English artists who spent years painting the Great War presented a portrait in smoke gray and mud brown of a land slashed open and scarred with Futurist lines of force. In contemporary films on the War, these colors, that bleakness, the blanched nature of a blasted world is conjured up, inspired by those canvases. No matter who the artist, Christopher Nevinson or the Nash brothers, no matter what the style, even John Singer Sargent, of a completely different generation, painted in dun: all colors are acid and dead, crushed under the weight of constant bombardment. Somehow, the Slade School of Art, presided over by a retrograde group of unenlightened artists, somehow produced a generation that created a modern language for a modern art. Few of that generation of war artists ever found peace and few were ever able to recapture the creativity inspired by carnage.

The war artist Paul Nash lived under the shadow of death is entire life. The artist grew up in difficult circumstances, marred by the depression of his mother which made a normal childhood impossible. From the distance of time, it is hard to diagnose her illness, but clinical depression seems likely, given that her son suffered from the same disease. His father, a barrister, moved the family to the country, in the vain hope that the isolation would be helpful to the health of his wife. As a child, Nash wandered though the woods and over the hills of Buckinghamshire, a beautiful and bucolic stretch of English landscape, beloved by the Romantic poets. But he explored, not as an artist, but as a child escaping a dark atmosphere. Indeed, Nash spent much of his childhood struggling with asthma, which, in the early twentieth century, could be fatal. For a child, not being able to breathe would be terrifying. The constant fight for breath must have taken up a great deal of psychic energy, for he arrived at adulthood without a vocation and fell into the notion of being an artist almost at random.

Buckinghamshire Countryside

When after a few years of commercial training as a book illustrator, Nash, who would never train as a painter, arrived at Slade School of Art, or “The Slade,” as it was called, and fell in love, as did all the young men, with Dora Carrington. Part of the rite of passage at Slade, aside from loving Carrington, was the indomitable Henry Tonks, a formidable teacher and severe critic of all things modern, from affront of Post-Impressionism to the horrors of Cubism and Futurism. Tonks had little regard for Nash, who had great difficulty in drawing in the Renaissance manner, the only way to draw, of course. The fact that Nash admired the pre-Raphaelites, especially Dante Gabriel Rossetti, did little to mollify his strict teacher. From the very start, Nash was a landscape artist and was never a figurative painter in the classical tradition, but he managed to develop his own somewhat stiff and original style. Before the war, he and his younger brother John managed to carve out reputations for themselves, existing somewhat uneasily among what the critic Roger Fry called les jenues or the equivalent of the Young British Artists of the twenty-first century. Then, as David Boyd Haycock pointed out in A Crisis of Brilliance. Five Young British Artists and the Great War, the War broke out, presenting each of the Slade group with a choice: to join or not to join?

The Great War disrupted artistic careers throughout Europe, decisively ending the pre-war avant-garde, scattering the international schools of modern art. Young British men were not conscripted until 1916, after over a year of terrible slaughter. Despite the problems with fragile health, which would plague him for the rest of his life, when the Great War came, Paul Nash joined up and became part of the London regiment of the home bound Artists’ Rifles. Like Stanley Spencer, Nash had commuted to London to attend classes, and like Spencer, he was wrenched from a England of the eighteenth century, pristine and unmarred by modernity. From the soft green hills of Buckinghamshire, topped by clumps of ancient gatherings of green trees, stretching along the edges of the Chiltern hills, Nash found himself in the region of northern France and southern Belgium. Once similar to Buckinghamshire in its verdant greenness, the border region butting up against Belgium and Germany, was the unlikely fault line of the Great War, sliced from the North Sea to Switzerland with lines of trenches. The rows of soldiers, separated by No Man’s Land, faced each other with the same precision as the lines of marchers in a Napoleonic war.

As his brother John Nash observed in his famous painting Over the Top, the generals in their wisdom ordered the men to march forward as if the military technology had not changed. But guns now fired smokeless powder, eliminating the centuries old cover of the cloud of smoke, guns were now repeating rifles, capable of firing some fifteen rounds per clip, and, behind the protective lines of the trenches lay the machine guns which rattled out a hail of bullets that could kill en masse without the gunners even having to aim. Transferring out of the Artists’ Rifles so that he could serve on the front lines, Nash arrived at the Ypres Salient, or front line bulge towards the German trenches in 1917. This was a territory that would be pounded by three battles, the First, Second, and Third Battles of Ypres, or, as the last battle was called, “Passchendaele.” An officer, with the lives of men under his command, Paul Nash, a man of the countryside, noticed the scars of war on the surrounding terrain. Writing to his wife, Margaret, he described what was a process of gradual destruction: “Everywhere are old farms, rambling and untidy, some of course ruined and deserted, all have red or yellow or green roofs and on a sunny day they look fine. The willows are orange, the poplars carmine with buds, the streams gleam brightest blue and flights of pigeons go wheeling about the field. Mixed up with all this normal beauty of nature you see the strange beauty of war. Trudging along the road you become gradually aware of a humming in the air, a sound rising and falling in the wind.”

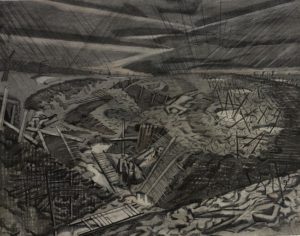

An eloquent observer of the landscape as carcass, Nash viewed the mangled land with the horrified and empathetic eyes of a nature lover: “I have seen the most frightful nightmare of a country more conceived by Dante or Poe than by nature, unspeakable, utterly indescribable. In the fifteen drawings I have made I may give you some idea of its horror, but only being in it and of it can ever make you sensible of its dreadful nature and of what our men in France have to face. We all have a vague notion of the terrors of a battle, and can conjure up with the aid of some of the more inspired war correspondents and the pictures in the Daily Mirror some vision of battlefield; but no pen or drawing can convey this country – the normal setting of the battles taking place, day and night, month after month. Evil and the incarnate fiend alone can be master of this war, no glimmer of God’s hand is seen anywhere. Sunset and sunrise are blasphemous, they are mockeries to man, only the black rain out of the bruised and swollen clouds all through the bitter black of night is fit atmosphere in such a land. The rain drives on, the stinking mud becomes more evilly yellow, the shell holes fill up with green-white water, the roads and tracks are covered in inches of slime, the black dying trees ooze and sweat and the shells never cease. They alone plunge overhead, tearing away the rotting tree stumps, breaking the plank roads, striking down horses and mules, annihilating, maiming, maddening, they plunge into the grave that is this land; one huge grave, and cast up on it the poor dead. It is unspeakable, godless, hopeless. I am no longer an artist interested and curious, I am a messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on for ever. Feeble, inarticulate, will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth, and may it burn their lousy souls.”

Paul Nash. After the Battle (1918)

In a 2014 program for BBC, Andrew Graham-Dixon visited the trenches at Ypres, retracing the steps of Nash through the zig-zag clefts in the ground, lined with corrugated metal. Graham-Dixon explained the mindset of Nash, who arrived with his childhood love of the tradition of the absurd in English literature. In showing how men “lived in holes,” Graham-Dixon stressed the surreal strangeness of this strange subterranean existence. It is no coincidence that The Hobbit and Middle Earth emerged as literature under the pen of J. R. R. Tolkien. In 2014, shortly after the BBC broadcast on Nash, an interesting book by Joseph Laconte discussed the emergence of a new kind of English literature after the War. A Hobbit, A Wardrobe, and a Great War. How J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918 was described as “For a generation of men and women, it brought the end of innocence—and the end of faith. Yet for J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis, the Great War deepened their spiritual quest. Both men served as soldiers on the Western Front, survived the trenches, and used the experience of that conflict to ignite their Christian imagination. Had there been no Great War, there would have been noHobbit, no Lord of the Rings, no Narnia, and perhaps no conversion to Christianity by C. S. Lewis.”

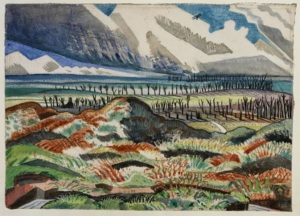

Paul Nash. Ruined Country (1917)

But for Nash, there were no redeeming spiritual features in the savage landscape that looked like the dark side of the Moon or this “Half-Buried World,” with its “Strange Metal Scars,” described by Graham-Dixon. The moonscape of Ypres was in stark contrast to Nash’s “English paradise” where he and his bother and sister grew up. Instead of hawks swooping through the woods near his childhood home, airplanes darted up and down the lines, photographing the trenches. Instead of the old moss-covered trees with their ancient reaching roots, there were only brittle surviving splinters pitching upwards from the ground. Vines and foliage were replaced with nests of twisted barbed wire. The only light was that reflected off the standing pools of water in the bomb craters, which floated on the larger sea of mud. Nash drew everything he saw and, absorbed in his work, fell in the trench and broke his rib. Little did he know that his service at Ypres was during a rare lull between battles, for while he was invalided home, his regiment was ordered into action, attacking the infamous Hill 60. Few returned.

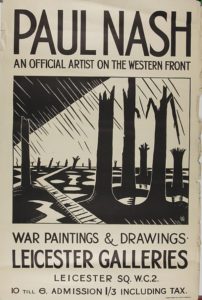

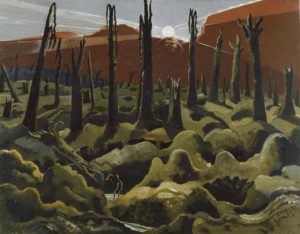

When Nash returned to these killing fields, it was an official War Artist, who has ceased to be an artist and who has become a messenger, determined to burn the public with the truth of war. “I realise no one in England knows what the scene of the war is like,” he wrote, “They cannot imagine the daily and nightly background of the fighter.” Towards the end of the war in May of 1918, Nash held an exhibition of his drawing of the war, dark and scratched and tight with anxiety and trauma, along with his first paintings. The title of the exhibition was The Void of War, a subversive phrase, rattling the censorious government, nervous about telling the truth in what was seeming like a never-ending war. Even more biting was the painting, We are Making a New World (1918), a landscape of acid green roiling mounds composed by endless shelling. Black trees rise up and lean in bewilderment, etched out against a background of sienna hills over with climbs a baleful white sun with piercing rays. This, then is the new landscape, made by explosives.

Paul Nash. We Are Making a New World (1918)

Nash’s best known painting was the huge history painting, stretching out six feet, The Menin Road. This was a commissioned painting, a project of the Ministry of Education, that was supposed to show the heroism and perhaps the glory of the war that was supposedly won. These two monumental and unsettling paintings show is a change in style for Paul Nash. According to Haycock, Nash came to terms with the Futuristic style of Christopher Nevinson, realizing that only a modern style could explain a modern war. Nash abandoned the careful crosshatching and the attention to detail in favor of a broad handling of unfamiliar oil paint, the color of mud and stagnate water. Once again, the huge painting confronts the viewer with emptiness, devoid of redeeming features, asking abruptly if the loss was worth the gain.

Paul Nash. The Menin Road (1918)

Like most of the landscape in this Flanders region, any of the previous villages and their roads had been obliterated. The title must be read as ironic, for the road is gone, but this painting marks the site of the Battle of Menin Road, part of the Third Battle of Ypres, the battle where his regiment was lost. In his own way, Nash was memorializing the deaths of the men he had once led. Like the Road, they no longer exist. Its Flemish road is Meenseweg or the Road to Menen, known to history by its French name, Menin. The Road, the main road out of Ypres, a way out of the Hell that was this battlefield, was one of the most shelled sites of the Great War. Nearby was the sadly named Sanctuary Wood and the great Hooge Crater, one of the enormous sinkholes characteristic of this war. Today the battlefield is overseen by the Menin Gate, engraved with the names of 54,389 officers and their men whose bodies were never recovered. For comparison, this number is only a few thousand short of the total deaths in the Viet Nam War.

Like many of his colleagues, Nash never really recovered from the Great War. His landscapes are impersonal, devoid of human presence and pathos. We see no dead or wounded, only the occasional soldier, navigating the pock marked ground. Depicting the causalities was a task he would leave to his strict teacher, Henry Tonks, who would be dragged into the twentieth century and forced to look it into its mutilated face. The pupil and teacher mirror each other, one showing the unprecedented landscapes, places that could have never existed without the intervention of a modern war; the other painted faces that were destroyed in an entirely new way. After the War, Nash turned to Surrealism as if to somehow express his inability to come to terms with peace and his struggle to overcome depression. He lived just long enough to paint the devastation of yet another war, this time concentrating on the air war in what must have seen like acts of re-execution of death. Nash, as his tombstone tells it, died in his sleep from heart failure, in his own way, a casualty of war.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.