The Deterritoriality of the West

Peter Goin and the Photographic Caption

In 1960 famed photographer Ansel Adams returned to one of his favorite sites in Yosemite, the Half Dome and waited for the moon to rise in the late winter afternoon. The towering half-mountain that arcs and thrusts itself upward was originally called “Tis-sa-ack” by the indigenous native American tribe Ahwahnechee or the ″Yosemite Valley People.″ Their “Cleft Rock” and the particular moon captured by Adams, a gibbous moon, meaning half full or only halfway visible, was a floating double for the cleft rock, cut in half by some ancient shearing mechanism. Science described the formation of the ancient outcropping somewhat prosaically: Half Dome “is the remains of a magma chamber that cooled slowly and crystallized thousands of feet beneath the Earth’s surface. The solidified magma chamber was then exposed and cut in half by erosion, leading to the geographic name ‘Half Dome’.” Half a rock and half a moon: Ansel Adams set up his Hasselblad on the tripod and selected an orange filter and began photographing. With the moon and Half Dome in dialogue, Adams recorded yet another moment in the pristine landscape. As Adams said, “..it is never the same Half Dome, never the same light or the same mood.” Of course, just as there is a dark side of the moon, there is also a dark side to Half Dome. Rearing its rising head almost 9,000 feet and made of quartz monzonite, the sheer face seems to beg to be climbed. A favorite of adventurous climbers, the flat face of the mountain has been scaled since 1875. Some free climb, using their bare hands, without support, but most use the existing cables erected for their safety. This route up the mountain is set up only in the summer months and is a necessary precaution to discourage the untrained from climbing on their own. Even this life-saving device is not foolproof and many people have fallen to their deaths. Since the first fatality in 1930, the dead have been mostly male, only four women have died. Oddly enough most of the deaths have involved hikers, not climbers. There have been weather-related deaths, the ground being wet from rain and unpredictable and bizarre lightning strikes. Some people became ill and, far from medical help, died. A few base jumpers whose chutes did not open perished. And finally, there were the eight suicides.

Ansel Adams. Moon and Half Dome (1960)

Yosemite is a pristine and protected wilderness, gently photographed by the greatest artists and countless amateurs, but there are other places, unprotected and vulnerable, also photographed but the images are anything but beautiful. The intention of the photographer is not to capture “moods” but to show destruction, the dark side of the earth where we live. To reveal the wastelands among us is the goal of photographer Peter Goin (1951-). The definition of “wasteland” differs slightly depending upon the time and the context the concepts of wasteland was developed. One idea about “wasteland” refers to land that cannot be cultivated, implying that land that cannot be put to agricultural use is a “waste” or wasted terrain. Land should be “used” and any land that cannot be put to productive “use,” or that has for some reason has become ruined is a wasteland. The idea of land being ruined is more modern, implying human intervention upon a site that was once useful but that is now empty, desolate, barren, bereft of any growing of living thing. From there is a slight slide to the notion of land that has been “wasted” and not utilized efficiently or effectively. In other words, a deliberate and destructive intervention has occurred. The work of Peter Goin, in fact, conflates these two degrees of “wasteland.” The territory he walks is the American West, the desert, often considered a wasteland for it is of marginal usefulness; and because of its apparent non-productivity, its inability to grow food, its unsuitability for agricultural cultivation, this is land that can be wasted. Land, which has been deliberately wasted, or to use another word or phrase, “sacrifice zones,” and it is in these spaces that Goin photographs. “Sacrifice Zone” implies that someone and something has been “sacrificed” deliberately through a series of decisions that had bitter consequences. Goin’s photography features zones of the West that have been sacrificed, along with the people who live near these sites, in the name of the Cold War.

In 1991, his book Nuclear Landscapes was published and these “landscapes” suggest yet another rephotographing of the world that once opened itself to the single lens of Timothy O’Sullivan, the zone system of Ansel Adams, and to the re-examination of Mark Klett. Goin forces his readers to study the West as a new kind of landscape, the site of the destruction of what was once America’s Garden of Eden. Goin’s website described years of the Cold War in which thousands of miles were bombed and poisoned and rendered unfit for human habitation: “The Atomic Energy Commission, shortly after World War II, recommended that a 640 square mile “testing ground” be carved out of the 5,400 square mile gunnery range in use by the military in southern Nevada. The testing of nuclear weapons was considered essential to national security, and President Truman authorized the opening of the Nevada Test Site on December 18, 1950. The first atmospheric test at the new site was conducted at Frenchman’s Flat on January 27, 1951. Hanford and White Bluffs, Washington had already been “condemned,” paving the way for the construction of facilities manufacturing weapons-grade plutonium.”

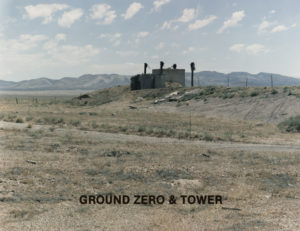

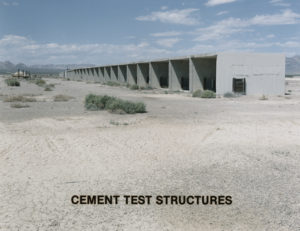

The account continued, “..the test site itself is strictly OFF LIMITS. Rarely have photographers been allowed to document the visual effects of the nuclear tests, and if so, their results were considered secret and confidential. These photographs are the product of a rare opportunity to photograph within the nuclear lands. The artifacts and sites throughout these nuclear lands represent icons in the range of myth and political ritual surrounding the nuclear age. This project contains these main sites: Nevada’s Nuclear Test Site, the Trinity Site in New Mexico, the Hanford Nuclear Area in Washington, and recently, the Marshall Islands’ sites of Bikini and Enewetak Atolls.” All these sites are linked in the sense that they all suffer from nuclear poisoning except one. Unlike the other places Goin ventured into, Handford, as a production center, was not bombed but is infested with plutonium. As for the other zones that were sacrificed: “One hundred and nineteen tests were conducted until a moratorium was established from 1958 to 1961. Until the United States and the Soviet Union signed a limited test ban treaty on August 5, 1963, another one hundred and two “devices” were detonated. Since 1963, however, all explosions have been underground.” The collection of forty-four photographs is the work of years, going back to the 1980s. Devoid of human beings, who are taking their lives in their hands to visit these places, the photographs have a buried irony: beautiful azure blue skies presiding over the pure white sands of the desert, now spiked with danger created by our own government. Any suggestion of grandeur or majesty if suppressed by the photographer’s discipline. These are the sacrifice zones; these are our nuclear landscapes.

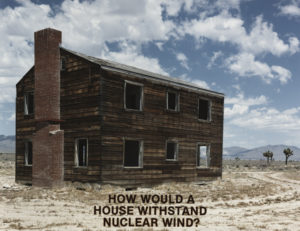

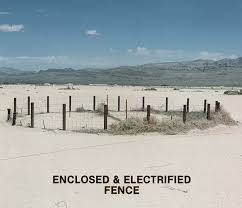

Each photograph that was taken by Goin totally lacks the mystery of an O’Sullivan or the velvet beauty of an Adams print or the objective purpose of the Rephotography Survey Project. These are icy cold photographs stripped of any emotion except shock and horror rendered in a straightforward and banal manner. He selected scars and wounds pockmarking the flat testing grounds. “Scenery” is abolished: there are no theatrical landscapes rich with nature. This land has been de-natured, stripped of anything natural and has become saturated with the culture of war and mutually assured destruction. These are places that are both dangerous and mysterious, not in the Gothic sense of mystery but in the sense of lack, lack of warning as to the dangers of what the United States government did, lack of information for the populations, also sacrifice, near these zones, and lack of an understanding of what was done in these deserts in the past. All we know is that we are looking at postmodern ruins, fragments of an old conflict which left behind clues that Goin noted in his stark captions. The few words block printed in sharp black across the bottom quarter of each image say nothing and everything, leaving a hole in between the word and the image that the viewer must struggle to fill in. There is only a question: what happened here?

In her important book, Tainted Desert: Environmental and Social Ruin in the American West, Valerie Kuletz reported that there were more than 928 above-ground and below-ground nuclear bombs that were reported. There were other tests that remain undisclosed by the military which took over certain selected desert areas and turned them into “nuclear landscapes.” This is land that is America but that is not available to Americans. It is land that has been withdrawn from the people. These are the western deserts, territories that have not been recognized by white people as being useful or useable. The people who have lived in these deserts, the Native Americans were witnesses to the seemingly endless rounds of atomic bombs detonated against their blue skies. The Los Alamos Trinity test sent a mushroom cloud over the Pueblo reservations. Kuletz wrote, “Naming and Mapping the nuclear landscape opens a space for other critical narratives to emerge..It provides an avenue to explore some of the ways human culture and politics transform place and ‘nature.’ Most importantly, mapping the nuclear landscape employes the political purpose of seeing purposefully unmarked and secret landscapes; it makes visible those who have been obscured and silenced within these landscapes.” Kuletz refers to a topic that Goin does not address directly: the people declared “marginal,” those who lived on–as at the Bikini atoll–nuclear sites and were moved and those how lived near the places where bombs were dropped and were exposed simply because they lived downwind and there were too many to displace. These are the “downwinders,” or those living east of the test sites. The Bikini islanders were, like the Native Americans, whose lands were desecrated, were not white and, for some reason, did not receive the care of the government that ruled them to be unimportant. There are suggestions that because they were not white, these indirect victims were considered marginal people, not worthy of respect or protection from the government. Along with the “zones” in which they lived, they were sacrificed. As she said, “Once made visible, the zones of sacrifice that comprise these local landscapes can begin to be pieced together to reveal regional, national, and even global patterns of deterritoraility–the loss of commitment by modern nation states..to particular lands or regions. Deterritorality is a term used to explain the construction of national and international sacrifice zones. It is a phenomenon that is becoming an increasingly common feature of power requirements. As such, territoriality is a particularly dramatic form of disembodiment–the percieved separation between self and nature.”

In 2016, Peter Goin wrote a brief article, “What Have We Done? Bearing Witness” and looked back upon his life’s work and discussed the concept of wasteland. He stated, “Within this nebula, I have felt compelled to bear witness to the fact that more than 1,000 nuclear bombs have been detonated within my Nevada homeland. In 1952, Nevada Governor Charles Russell, showing his ignorance of climax ecology, said, “…we had long ago written off that terrain as wasteland, and today it’s blooming with atoms!” Goin is a member of the Atomic Photographers Guild, a group of artists dedicated to bearing witness the toll of the atomic age. Founded by Robert Del Tredici in 1987, just two years before the Fall of the Berlin Wall, the Atomic Photographers Guild, or the APG as it is called, has been building an archive of images showing atomic destruction. The group includes the first photographers to record the impact of the first bombs. Prints of Berlyn Brixner, present at the Trinity Test and Yoshito Matsushige who walked through the ruins of Hiroshima form the foundation of the collection. Del Tredici explained the motives of this unusual group of photographers: “I first clashed with fissioned atoms in 1979 at Three Mile Island while documenting the faces, places, and voices of America’s worst nuclear accident. Then I went after nuclear weapons, first meeting the survivors of Hiroshima, then photographing the men and machines of the Bomb throughout the USA, Europe, Canada, and the former Soviet Union. All along the way, I met other image-makers bent, like myself, on capturing different facets of the world’s nuclear arsenals. In 1987 we pooled our energies and images to contribute towards revealing a nearly invisible entity in its own mostly unseen universe.”

Robert Del Tredici. The Yellow Brick Road from The People of Three Mile Island (1980)

Because, from its very beginnings, the atom bomb was a secret, a precedent was set by the government. A strange precedent it was–exploding atomic bombs within sight of Reno and Las Vegas in Nevada, testing weapons of all kinds in the deserts adjacent to the test sites, willfully irradiating soil for thousands of years to come. All of this irresponsible behavior took place in plain sight, the dangers to the public concealed by popular culture and the Bikini bathing suit. The actual places where the military confiscated public lands for their own use were off limits to the public as were the activities practiced within the parameters. The result was a silence that, after the Cold War was supposedly over, resulted in what Jessie Boylan called “Atomic Amnesia,” in her article on “Photographs and Nuclear Memory.” For Americans who lived outside of the vast atomic deserts, an unexpectedly large segment of the West, out of sight meant out of mind. After the Cold War, we were eager to come out from under the nuclear cloud that had threatened us all and forget the grim feeling that tomorrow could very well not come. But Goin’s Nuclear Landscapes, arriving in 1991, two years after the Berlin Wall was dismantled, served as insistent reminders. Each image was embedded with its own meaning that was descriptive, overlaying images that were unfamiliar to the viewer, because these were places we would not go. The photographs, on their own, would have lacked impact. But the thick and intrusive black san serif letters act as fences, forbidding us to visually enter into what appears to be a landscape and keeps us outside, on the periphery, reduced to helpless looking. Goin’s use of “captions” or text is odd, unlike other artists. Kruger incorporated her writing into her photographs and text became image; Magritte used handwritten disclaimers as misleading labels; Duane Michaels wrote over, under, and around his images. Goin floats the lettering over, if not above, the surface, rather like a Cubist collage, in a rude invasion of the photograph, refusing to be marginal or in the margins. By incorporating text and image, by allowing the text to trespass upon the terrain of the image and to become more than a semiotic sign, Goin may have created a series to pictorial tombstones, each bearing its own inscription of death by atomic testing.