Jacob Riis and the Other Half

During a period of open borders, the Age of Mass Migration, which extended from 1850 to 1913, brought thirty million individuals, men, women, children, and families to the New World. They came in ships that were built increasingly larger as shipping companies raced to make money from emigrants desperate for a new start. While the Asians headed for California, Europeans landed in New York. From 1886 on their first sight of the new home was the Statue of Liberty, rising from Liberty Island. A gift from the people of France to the people of America, the colossal female symbol was designed by sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi (1843-1904) with Gustave Eiffel (1832-1923) as the “internal engineer.” To this work of art with impeccable aesthetic credentials was added a long and uplifting name, The Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World (La Liberté éclairant le monde).

This famous statue was so fitting for its purpose and came to embody the hope and faith that drove so many millions across the Atlantic Ocean that it seemed appropriate to add a written message to reinforce the visual inspiration of Lad Liberty. Written by Emma Lazarus (1849-1887) in 1882 and installed on the pedestal in 1903, the brief poem read,

“Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame, with conquering limbs astride from land to land; Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand a mighty woman with a torch, whose flame is the imprisoned lightning, and her name Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command the air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame, “Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she with silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore, Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

That America could absorb such huge numbers of so many European nations in such a short time was an extraordinary achievement. Contrary to fears and urban legend, the emigrants were assimilated in one or two generations and melted into the American mainstream. But the journey of the twelve million who arrived at Ellis Island was a difficult one, involving terrible housing, exploitive labor situations, crime and illness, extreme poverty and the failure of governmental institutions to take responsibility for the newcomers. So great was the suffering of these early arrivals that the cumulative mass of misery gave birth the to first major Progressive movement at the beginning of the twentieth century. Working in New York at the same time as Edward Curtis was photographing Native tribes in the West, Jacob Riis (1849-1914) was an early believer in the adage, “the whole world is watching,” meaning if you used the camera of show the truth change would come. Unlike Curtis who was criticized posthumously for his refusal to document the true misery of the Native Americans on reservations, Riis, an emigrant himself from Denmark, was dedicated to showing the unpleasant truths of a city overwhelmed by millions of people, who arrived without language, without jobs, without education into a situation where the only help forthcoming was from friends and neighbors.

Jacob Riis. Five Cents Lodging, Bayard Street (1889)

When he arrived in America in 1870, Riis possessed the ability to speak English, which put his prospects for employment ahead of those who could were not English-speakers, but he, like many immigrants who had no relatives elsewhere in the United States, was trapped in New York, competing with thousands of others for menial and temporary jobs. For years he drifted, hungry and homesick and alone, until in 1873 he trained in telegraphy and a year later was hired as a reporter. Due to his literary ability as a writer, his rise was nothing short of remarkable, from a hungry and wandering itinerate laborer to an emigrant who wrote editorials for the South Brooklyn News, paper he purchased in 1875. By 1877, he had married his childhood sweetheart from Denmark, quit newspaper business, learned photography and finally found a home as a police reporter on the New York Tribune. Although he was never political in the traditional sense, Riis was a dedicated reformer and never hesitated to use his editorializing pen to both describe and comment upon life in the American city of New York, life among the high and the low. A Protestant to the bone, he firmly believed not just in the ultimate value of hard work but also in the possibility of awakening the social consciousness of landlords and factory owners to to good for their tenants and laborers. His rather naïve unpolitical optimism was astonishing given that Riis worked out of the Mulberry Street police station, located in the midst of the worst slums in the world. Here, at Mulberry Bend and Bone Alley, the location of notorious neighborhoods, such as Bandit’s Roost and Five Points.

Jacob Riis. Bandit’s Roost. 59 1/2 Mulberry Street (1890)

In his 2001 review of The 19th-Century New York City Neighborhood That Invented Tap Dance, Stole Elections, and Became the World’s Most Notorious Slum by Tyler Anbinder, Kevin Baker described the origin of Five Points. Once the site was a lake called “the Collect” but by 1800, this five acre lake was ringed by tanneries and slaughterhouses. There refuse spewed and the odors rose rank into the air. So horrible was this “lake” that in 1825 it was filled in, obliterated, built over by a neighborhood called Five Points. It took only ten years for this site to revert to its original condition, this time as “America’s First Slum,” full of bars and bordellos and much visited by tourists. During the Irish Famine of the 1840s, Five Points received the first of many ethnic influxes of immigrants, becoming a melting pot, with a different ethnic gang to every block. To this day, in more peaceful times, Little Italy is still in the middle of Chinatown. Eighty years after the Collect was covered up, Jacob Riis took it upon himself to reveal to the affluent people of New York, the true conditions surrounding his headquarters, Mulberry Bend of Five Points. As Riis wrote later in his seminal 1890 work, How the Other Half Lives, “The whole district is a maze of narrow, often unsuspected passage ways—necessarily, for there is scarce a lot that has not two, three, or four tenements upon it, swarming with unwholesome crowds.” He vividly describe the “bend” itself: “Where Mulberry Street crooks like an elbow within hail of the old depravity of the Five Points, is “the Bend,” foul core of New York’s slums.” This is the career of the self-taugh photographer began, in the heart of foulness, and this is the site of investigative journalism.

Jacob Riis wrote of these homeless boys or “street arabs:”

“Whence this army of homeless boys? is a question often asked. The answer is supplied by the procession of mothers that go out and in at Police Headquarters the year round, inquiring for missing boys, often not until they have been gone for weeks and months, and then sometimes rather as a matter of decent form than from any real interest in the lad’s fate.”

These appalling social conditions were not accidental but purposeful through a profitable union of industrialists who were anxious to take advantage of the unending tide of cheap labor and politicians who benefited from abetting the financially powerful. Absentee landlords ruled supreme over this lucrative territory, buildings earned nothing but revenue because the tenants could not demand improvements or upkeep. The so-called “rear” apartments or the interior units were completely enclosed and a cooperative court of law ruled that the inhabitants had no legal right to air or light. All of the political and social and economic powers worked in concert to keep the suppressed newcomers in living conditions so terrible that they would not rebel or protest because, packed in a small area often swept by epidemics, they were so preoccupied with mere survival. Jacob Riis became a voice to speak for those who were not yet citizens, who could not speak English, who had no financial resources, no education, no home and only a desire for a better future through hard work. Traditionally, governments had relied upon the good will of citizens to help the poor but by the end of the nineteenth century, the population of the slums of New York was one million human beings, suffering and dying of very work and unhealthy living and working conditions–a situation far beyond any private efforts to alleviate. Utilizing relatively new technology, fast film and the flashbulb, better known as the magnesium-cartridge pistol lamp, Riis captured in an instant the misery that lived a half life in alleyways and cellars and in tiny dank rooms. From 1888 on, Riis used the novelty of “magic lantern” to show slides to his viewers who considered such vivid representations of poverty to be the equivalent of visiting the alleyway of “Bandits’ Roost” in person. His first audience were the members of his camera club, who had little first hand experience of the slums, much less of life at the Mulberry Street police station.

As the authors of Rediscovering Jacob Riis: Exposure Journalism and Photography in Turn-of-the Century New York (2007), Bonnie Yochelson and Daniel Czitrom pointed out the police stations in the slum territories did more than keep the peace, they acted as social services in an area where there was no there government presence. As Daniel Czitrom wrote, “Indeed Gilded Age police work meant a great deal more than the prevention and solving of crimes. Policemen of the day were very visible public agents, particularly for the poor, the recent immigrants, and the city’s huge ‘floating’ population. They routinely provided lodging and sometimes food for the indigent, helped lost children find their parents, aided accident victims, transported the sick to hospitals, stopped runaway horses, fished unidentified bodies out of the harbor, and removed dead animals from the streets.” As Tom Buk-Swienty noted in his 2008 book, The Other Half: The Life of Jacob Riis and the World of Immigrant America, that it was also the task of the police to dispose of the annual harvest of one hundred bodies of infants found in the streets, find orphanages for the five hundred abandoned infants. Most of these children would die.

The documentary photographs of Jacob Riis in How the Other Half Lives were marked by his own experience of landing in New York with less that fifty dollars, carrying no luggage, and being thrown into an unfamiliar environment. He knew what it was like to live in the shadows of looming tenement buildings, bordered by shacks and squalor, places where the basic ingredients for a healthy life, fresh air and sunshine, rarely visited, alleyways where children huddle together for warmth, tiny apartments where up to a dozen people existed and did piece work for factories. One wonders especially at the photographs of the children taken by Riis–were they abandoned by their parents, pushed out of their families? The girls seem to have been allowed to stay with the family, caring for the endless stream of newborns as “little mothers,” allowing their own mothers to work as full time laborers. As Riis wrote in his 1892 wrenching book, The Children of the Poor, on “The most pitiful victim of city life is not the slum child who dies, but the slum child who lives..Every time a child dies, the nation loses a prospective citizen, but in every slum child who lives the nation has a probable consumptive and possible criminal.” These desperately poor people lived in daily filth, “victims,” Riis called them, of a larger society that literally never saw them.

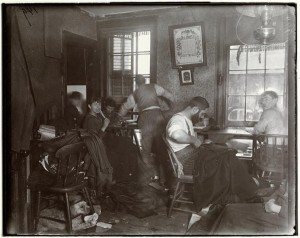

Jacob Riis. Knee-pants” at forty five cents a dozen—A Ludlow Street Sweater’s Shop (1890)

What made Riis different from the other writers and journalists who wrote of the immigrants was his point of view–he humanized the same people others referred to as “dirty” and “ignorant” and forced his audiences to bear witness to victims of governmental inaction. Among the gentry and well-heeled middle class, the common view of the poor was that they had brought their condition upon themselves. But Riis set out to change minds and hearts, writing seven books and giving countless lectures. Although he considered his photographs as visual aids to his mission, it is these images that became famous. Today his characterizations of various ethnicities, while typical of his time, would be considered patronizing, condescending, and offensive, but the raw untutored images have remained relevant. A capitalist who believed in the power of business as transformative, Riis had little faith in government intervention. But the photographer can be credited, at least in part, for impacting the progressive movement, for he worked with Theodore Roosevelt, who in 1895, was the president of the Board of Police Commissioners and spear-headed reforms in New York City. “I have read your book, and I have come to help,” Roosevelt said. It was Riis who took the future president on a tour of the slums of New York. Jacob Riis would end his lecture with the question “What will you do?” It was Roosevelt who provided the answers.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.