ROGER FENTON IN THE CRIMEA

The Beginnings of War Photography

The Crimean War

It would be interesting to create a history out of the importance of maps and the stories they tell. Take the map of Russia for example. The nation is huge but it is locked between the Arctic Ocean to the north and the landmass of the European continent to the west. Historically Russia had only three ports suitable for modern shipping and trade, St. Petersburg on the Baltic Sea, that gives access to norther Europe and the Scandinavian nations, Vladivostok which is on the Sea of Japan, making it ideally situated for Asian trade, and Sevastopol, which is located on the Crimean peninsula, is Russia’s only warm-water port and the only access to Europe by sea. But there is a problem with Crimea. Not only is the territory a peninsula, it is dangling down alone into the Black Sea which was overseen and controlled by the Ottoman Empire or present day Turkey. For three centuries, the Crimea once belonged to the Ottoman Empire in league with the indigenous inhabitants, the Crimean khans, which established Crimean Tatar state. Using the rather specious logic that the Tatars were somehow related to Russians, Catherine the Great seized the territory in 1774 and many of the Tatars migrated to Turkey. The Russians now had their port but the only way out to the Black Sea was the Bosporus Strait, which was still in Ottoman territory. But the Bosporus merely allowed access to the Black Sea. To get to the Mediterranean Sea it was necessary to go through yet another strait, the Dardanelles, also controlled by the Turks. Russia and the Ottoman Empire would spend the next hundred years in conflict over who controlled these important gateways to Southern Europe. The map tells the entire story of Russian history from the time of Peter the Great to this very day. Without the port of Sevastopol, Russia is completely isolated from southern Europe. Without access through the Straits, Sevastopol was merely a parking lot for the Russian fleet. Given the significance of the Crimea to Russia, the fact that Russian Premier Nikita Khrushchev gave the peninsula to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1954 has to be one of the strangest gifts in history. The reason given at the time was explained as an acknowledgement of “the economic commonalities, territorial closeness, and communication and cultural links” between the Crimean territory and the Ukraine. It is probable that Khrushchev assumed that the Ukraine would always be under Soviet control forever and that the Soviet Union was eternal. As current events indicate, this part of Eastern Europe, multi-ethnic and multi-religious has always been a source of conflict and bloodshed. In the Great War, a tragic battle would be fought for the Dardanelles at Gallipoli. But, as if in a prelude of that war, a preliminary war was fought over access to the seas and this war was called the Crimean War. Czar Nicholas I (1796–1855), sensing correctly that the Ottoman Empire was weakening, decided to strike against the ancient adversary in 1853. Not only did he want to secure his sea routes he also contended that, for religious reasons, the Muslims had to be attacked as part of a crusade. Because of the supposed religious component thrown into the mix, Nicholas expected the Christian European nations to side with him, but he was wrong. Russia and France, or to be more precise the Russian Orthodox Church and the (French) Catholic Church, got into a dispute over religious sites in the Holy Land. Therefore, the European experience with Russia’s attitude and the concern of the great powers over the nation’s expansion led, to the surprise and consternation of the Czar, France and England to join with the Turks to check their large neighbor directly to their east. Once again a glimpse at the map shows, in a age before intercontinental railroads, the vast physical distance between Russia and western Europe that accounts for the lack of comprehension on the part of Nicholas of the rest of Europe. The alliance between two Christian nations with a Muslim Empire caused great anger and bitterness within Russia and was widely felt to be betrayal of one Christian nation by other Christian nations. During the lead-up to the Crimean War, Prince Albert in England warned against such an adventure, one that would gain Great Britain little for the purpose of containing Russia but, a consort without power, he was not listened to by Parliament. The British had a rosy view of themselves as being the defender of the weak against strong and the injustice of Russia’s aggressive move against the Turks could not be allowed to go unanswered. The Russians occupied Ottoman territories, modern day Moldova and Romania, and sank the Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Sinope in 1853. For England, the deciding factor was the fear that their own fleet might be blocked from the Dardnaelles by Russia and so, when France and Great Britain entered on the side of the Ottoman Empire in 1854, began what some call the first modern war. But it was modern only in that the Crimean War predicted some of the conditions and problems of the Great War, complete with trenches, pointless deaths, and incompetent leadership. The map gives some clues as to what went wrong. Apparently the French and the British rushed in wearing their best intentions and their fanciest uniforms and leading their bravest young men to their deaths. The only element not brought to the conflict was planning–everything from clothing to strategy was absent. Predictably, the war went badly. Military leaders were born into their right to lead troops, regardless of whether or not they had any ability at all, and this war highlighted the problems of hereditary privileges without doing anything about this illogical system until the twentieth century. What made the Crimean War different from its predecessors was the scope and reach of the press and the rise of the war correspondent, particularly the famously irascible William Howard Russell (1821-1907) who was embedded with the troops, observing everything and writing back to the Times. It is to Russell that the British owe the famous words, “the thin red line,” writing, “The Russians dash on towards that thin red streak topped with a line of steel..” referring to Sir Colin Campbell, commander of the “Thin Red Line.” Russell’s writing was so vivid that he brought to light the lack of ambulances, the lack of hospital care for the sick and wounded and the unbelievable lack of effective leadership that resulted in even more deaths, and his descriptions of the carnage he had witnessed stood on their own, against government denials of disaster. It was his eloquence that brought eternal fame to the ill-fated Charge of Light Brigade on October 25th: At ten minutes past eleven, our Light Cavalry Brigade advanced. As they rushed towards the front, the Russians opened on them from the guns in the redoubt on the right with volleys of musketry and rifles. They swept proudly past, glittering in the morning sun in all the pride and splendour of war..A more fearful spectacle was never witnessed than by those who beheld their countrymen rushing to the arms of death. At the distance of 1200 yards the whole line of the enemy belched forth, from thirty iron mouths, a flood of smoke and flame, through which hissed the deadly balls..With courage too great almost for credence they were breaking their way through the columns which enveloped them, when there took place an act of atrocity without parallel in the modern warfare of civilised nations. The Russian gunners, when the storm of cavalry passed, returned to their guns,and poured murderous volleys of grape and canister on the mass of struggling men and horses. At thirty-five minutes past eleven not a British soldier, except the dead and dying, was left in front of these bloody Muscovite guns.

The “rush to the arms of death” across open ground in the face of guns was more a matter of stupidity than valor, but the poet laureate of England, Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892), immediately re-wrote what was a spectacle of human waste into an ode to selfless bravery. The poem begins with: Half a league, half a league,

And ends with: When can their glory fade?

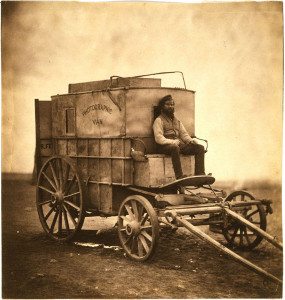

It is thought by some that it was Prince Albert, who, disturbed at the never ending bad news, delivered by an Irish correspondence, sent his trusted photographer, an Englishman and a man of the upper class, Roger Fenton (1819-1869), to the Crimea to investigate on his own. Other accounts maintain that it was a Manchester publisher, Thomas Agnew who hired Fenton. Whatever or whoever propelled Fenton into the Crimean peninsula, he was on the scene from March to June of 1855 as one of the first war photographers. He arrived with a letter of introduction from the Prince and his trip was funded by the secretary of state for war. According to Sarah Greenough, one of Fenton’s biographers, writing in All the Mighty World: The Photographs of Roger Fenton, 1852-1860 (2004), he was granted unfettered access to the battlefields, unlike the critical Russell who was impeded whenever possible. Likewise, as the dates of his stay indicate, Fenton arrived in the pleasant spring, months after the bitter winter that had nearly broken the ill-equipped army. Unlike the loud and noisy prose of Russell, Fenton’s camera was mute. Although it has been noted that Fenton seemed uncritical of the war, and it is certainly true that one looks in vain for images of the dead and wounded, suggesting royal patronage, the photographic technology of the time was against whatever desire Fenton may have had to record the reality of the war. By this time, he was photographing with collodion, a process that required a large amount of equipment, from hundreds of glass plates, to a variety of chemicals, all of which needed a wagon. The exposure times were long and the best subjects for the camera at this time were either inanimate or carefully positioned for long poses. Roger Fenton’s Photographic Van

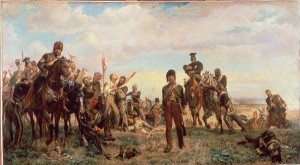

A comparison between the military paintings of the day and the photographs of Fenton immediately shows the lack of drama, excitement, danger and dash in his photographs. Lady Elizabeth Butler (1846 – 1933) was one of the greatest military painters of all time and she was hardly uncritical of the Crimean War. While the political and military leaders of the war denied the suffering of the men in the ranks, their fabrications were stopped by the true stories told by the men who returned home after the war. Butler inherited the revised account of the campaign in Crimea and her paintings of the tragedy, not the glory, of the war. Lady Elizabeth Butler. Balaclava (1876)

(The aftermath of the Charge of the Light Brigade)

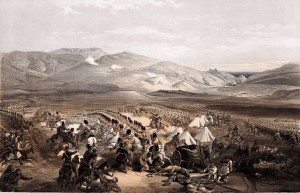

Butler’s small paintings, full of pathos and human suffering, caused a sensation when they were shown, decades after the war was over clearly, demonstrated the costs and folly of war–even a war “won” by England. But perhaps a more fitting comparison would be to the lithographs of William Simpson (1823-1899) who, like Fenton was on the scene in Crimea and, like Russell, Simpson, who had been sent by a British print dealer, Dominic Colnaghi, strove for accuracy. Simpson’s panoramic view of the Charge of the Light Brigade was capable of visualizing the words of Russell, the later poetry of Tennyson, and the spectacle of war itself. William Simpson. Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaklava (1855)

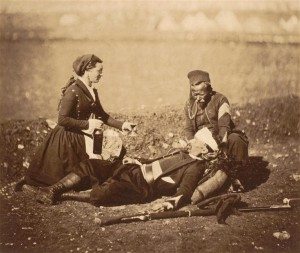

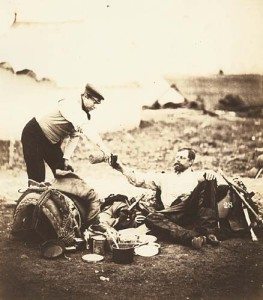

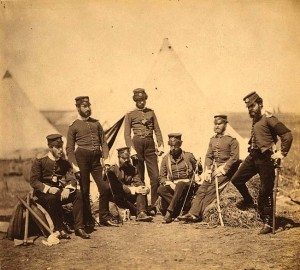

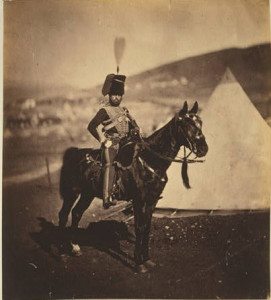

As Tennyson wrote of the senseless charge: “Forward, the Light Brigade!” It is important to recognize that the Crimean War was the first “media” war and the use of the telegraph greatly speeded up the transmission of the news from the war to the public. In contrast to the powerful words of Russell and the stirring paintings of Butler and the contemporary prints of Simpson, Fenton’s photographs are straightforward and informative and bland. He conscientiously photographed officers and enlisted men, the encampments and the vistas and the battlefields. Compared the photographs of the Civil War in America, which did not turn from the carnage, Fenton was discrete. He saw dead bodies, remarking, “..life is squandered here like everywhere else..” His purpose was to collect data in the form of photographs that could work around only the edge of war. The fighting itself was always elsewhere, off stage or, as he described “somewhat distant..” and the soldiers are always in between fights, waiting for orders. There is a striking image of a woman dressed in a hoop skirt tending to a wounded soldier, in this the first war the established the idea of ambulances and nurses on the front, led by women like Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole. Images of class differences abound. Officers are waited on by their military servants, or “batmen.” Officers arrived arrayed in magnificent battle dress and rode expensive horses only the wealthy could afford. These officers purchased their commissions the way the purchased their horses and the infamous Lord Cardigan, the leader of the unfortunate Calvary that charged into Russian gunsights, had purchased his position for forty thousand pounds. The enlisted men who did the fighting while their superiors watched through binoculars were spent and exhausted when Fenton found them. In contrast to the strutting officers, having no need for publicity, they simply stand obediently before Fenton’s camera. The Crimean War was, oddly enough, a war that has left us with many sartorial contributions. James Brudenell (1797-1868), the seventh earl of Cardigan wore a woolen knitted vest against the cold winter and today’s buttoned and sleeved sweater still bears his name. Although the cardigan sweater has changed from the one that Cardigan wore, the Ragland sleeve has not. Lord Raglan (1788-1855), Fitzroy James Henry Somerset didn’t know the difference between the French and the Russians but he knew his fashions. The Lord went to war with a coat with specially designed sleeves which began at the collar line, starting a style of coat, jacket, or blouse still worn today. And then there was the “balaclava” named after the town itself. Originally known as Uhlan Caps or Templar Caps these knitted headgear covered the head and the mouth and chin, leaving only the eyes exposed. As Helen Rappaport wrote, Back home the women of England were rallying to the defence of what an enraged Frances Anne, Lady Londonderry had described to her friend Disraeli as the willful neglect of ‘this little heroic wreck of an army’. The Queen and her daughters headed an army of women who were turning out warm mittens, scarves, gloves and socks by the score. Even on Christmas Day the knitting needles were clacking at Windsor: ‘The whole female part of this Castle, beginning with the girls and myself … are all busily knitting for the army,’ Victoria wrote with pride.

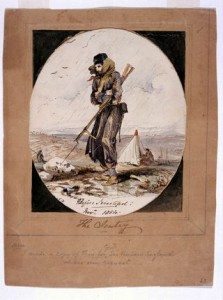

A substitute sent to the Crimea when the official winter clothing for the troops was delayed, this warm cap, the “balaclava” is a today a favorite for the military, skiers and robbers the world over. Winter 1854 in the Crimea

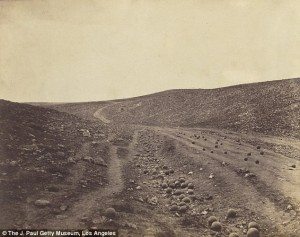

Fenton’s intention was to collect the kinds of images that would provide a truthful image to pair with or to silence the words of Russell. He wanted to bind this collection of 350 photographs into an album, priced to sell to the ruling class. Much of his work should be categorized as portraiture, genre scenes of everyday life in the camps of Balaclava, his home for three months. Fenton did not photograph the site of the actual Charge of the Light Brigade but a gully stretching into the barren terrain filled with Russian cannon balls and nicknamed by the troops “The Valley of Death” because of the constant barrage. The bleak featureless terrain was devoid of life and empty of activity and bereft of meaning. On one occasion, the photographer participated in a battle and witnessed at first hand the lack of management and military strategy that characterized the war in the Crimea, a brave act which put an end to his tourist attitude to the war, so evident at the beginning of his stay. With the summer not far away Fenton contracted the disease of the war, cholera, and returned to England. The Crimean War ended for all intents and purposes in 1855 when the Russians abandoned Sevastopol after a year long siege. The British were too spent to follow up on the victory and in 1856 the Treaty of Paris officially ended the war. The contested straits were protected from Russia and the Ottoman Empire and opened for European trade. In 1915 a new Dardanelles Campaign began with Gallipoli, proving that, despite the fact that this was the first “media war,” the lessons of the Crimean War had gone unlearned. If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.

Half a league onward,

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

‘Forward, the Light Brigade!

Charge for the guns’ he said:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

O the wild charge they made!

All the world wonder’d.

Honour the charge they made!

Honour the Light Brigade,

Noble six hundred!

Was there a man dismay’d?

Not tho’ the soldier knew

Someone had blunder’d:

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do and die:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.