Photography as Re-Enactment

Part Two

When photographer Edward Curtis began his monumental twenty volume project on the Native American Tribes of North America, the term “documentary photographer,” had yet to be invented. Such was the certainty that a photograph was a document and an irrefutable record of what exists or what had happened, that in 1907, on the other side of the country, Alfred Stieglitz was in the midst of a struggle to convince his New York audience that photography could be art. British director and producer, John Grierson put the word “documentary” to new use in 1926 as a suggestion for a new kind of movie, and the new word quickly migrated to the field of photography where the two words became a pair: “documentary photography.” In writing The First Principles of Documentary, Grierson wrote,

“We believe that the cinema’s capacity for getting around, for observing and selecting from life itself can be exploited in a new and vital art form” and “We believe that the materials and the stories taken from the raw can be finer (more real in the philosophic sense) than the acted article.” and “In documentary we deal with the actual, and in one sense with the real. But the really real, if I may use that phrase, is something deeper than that. The only reality which counts in the end is the interpretation which is profound.”

But Grierson also revealed the purpose of the documentary, “I look on cinema as a pulpit, and use it as a propagandist.” In fact, the filmmaker’s concept of a documentary was activist and socially aware. As he stated, “The basic force behind (a documentary) was social and not æsthetic. It was a desire to make a drama out of the ordinary, to set against the prevailing drama of the extraordinary: a desire to bring the citizen’s eye in from the ends of the earth to the story, his own story, of what was happening under his nose.” If one agrees with Grierson that the purpose of a documentary was to raise the consciousness of the viewer, then, clearly, a strong commitment to the content was a prerequisite, and it would seem that Edward Curtis and his very genuine sense of purpose would quality as a “documentary” photographer. Here, it would be helpful to distinguish between documentary photograph and photojournalism in that photo journalism is necessarily tethered to the “news” that which is current and occurring in the moment. Whatever else he might have been, Curtis was no photojournalist and needs to be thought of as an independent self-educated actor, engaged in his own obsession. He can, in effect, be thought of as an artist, who constructed a narrative of a doomed way of life. On one hand, the official government response to the Native American way of life, that which was still in existence, was repressive, on the other hand, tourists were enthralled with the alien culture in their midst.

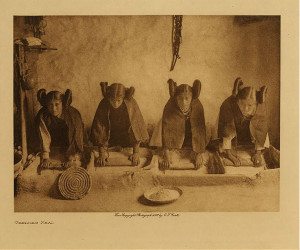

This image of Hopi women grinding corn was directed by Curtis whose request to look at the camera amused the young women who were used to looking at corn as they were grinding it.

Curtis felt that, if Native American culture were not recorded immediately, it would disappear. And the best academic minds agreed unanimously that they were witnessing the last of the “Indian.” None, not even Curtis, asked why this culture should be wiped away; its extinction was simply accepted. It was this urgency of acceptance that ironically drove the photographer on his documentary journey. In her 2005 article, “Constructing the World. Documentary Photography in Artistic Use,” Bettina Lockemann reminded her readers of the distinction between authenticity and representation and she also raises the issue of aesthetics, i.e. beauty and document. Theoretically, in a “document,” the maker disappears, style is eschewed and personal approach is elided in the search for the purity of authenticity, but in practice, the knowledgable and trained eye can easily see the distinctions, that are quite unique, between documentary photographers, Dorothea Lange and Ben Shahn and Walker Evans. Authenticity must double back upon and within itself and becomes a representation. Bur representation presents other problems: who is constructing the representation and who is being represented? The relation is analogous as that of the One to the Other. As photohistorian John Tagg asserted in his 1999 essay, “Evidence, Truth and Order: A Means of Surveillance,”

“Like the state, the camera is never neutral. The representations it produces are highly coded, and the power it wields is never its own. As a means of record, it arrives on the scene vested with a particular authority to arrest, picture and transform daily life; a power o see and record; a power of surveillance that effects a complete reversal of the political axis of representation, which has confused so many labourist historians. This is not the power of the camera but the power of the apparatus of the local state which deploy it and guarantee the authority of the images it constructs to stand as evidence or register a truth.”

Tagg’s analysis of photography in the nineteenth century was a critique from a Foucauldrian point of view. In 1975, Michel Foucault published the seminal work, Discipline and Punish, in which he examined the culture of surveillance, which, Tagg argued, shifted to the camera whose baleful eye came to rest attentively upon certain bodies that need to be docile. These would be the bodies of the Other, whether the criminal or the mad person or the non-European. Wielding a camera is an act of privilege and power, a granting of the gift of being able to represent, to not be represented. Tagg wrote an entire book on what he eloquently termed The Burden of Representation (1988) that surely informed the later critiques of Edward Curtis, for his Native Americans certainly reenacted the role of the sentimentalized Other, made safe for public consumption thorough decades of suppression and surveillance. Now safely relocated on reservations, they would be examined, interrogated and then represented and explained through the lens of the all-powerful apparatus of construction, the camera.

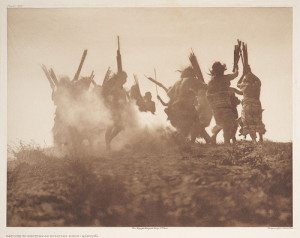

Edward Curtis. Dancing to Restore an Eclipsed Moon.

As Martha H. Kennedy explained in her 2001 preface to The Plains Indian Photographs of Edward S. Curtis, “He and many of his contemporaries believed strongly that all Indians were members of a ‘vanishing race’ and admired what ere perceived as their heroic qualities as ‘noble savages.’ Attentive though he and his assistants were to the differences between the Plains Indians and other native people, Curtis could not help but be shaped in his photographic approach by these culturally ingrained perceptions, such as the sweeping generalization that all native peoples were one homogeneous culture.”

Called the “Shadow Catcher” by Native Americans, although he also used dry plates, Curtis was surely one of the last major photographers to use wet plate photography, sliding his glass plates in and out of his large view camera. The images he made are old fashioned, even in their own time, as if he were deliberately evoking the nostalgic albumen tints that semiotically speak of “the past.” In fact, in his book 1998 book, Edward S. Curtis and the North American Indian, Incorporated, Mike Gidley makes the case, and, one tends to agree with him, that Curtis was involved in a vast enterprise of “representation” of the Native American, something he termed “the beautiful” in that “vanishing” life. It wasn’t until he gathered information for his last volume on the indigenous tribes of Alaska, the Nunivak, that Curtis found a culture on the isolated Univac Island that had not been altered by missionaries. What Curtis found in1928 was an untouched world that would be eradicated ten years later by Swedish missionaries who destroyed the extradorinaiy masks in the name of Christianity and civilization.

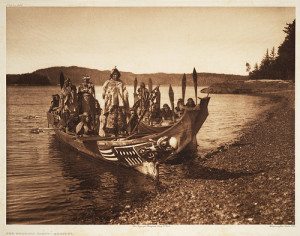

Edward Curtis. Wedding Party. Kwakiutl

Today, we tend to think of Edward Curtis as being caught between different attitudes towards the Native Americans. For decades his work, The North American Indian (1907-1930), had been forgotten, but, ironically, during the very years of a long overdue Native American political activism, his work was rediscovered in 1970 in the bookstore basement by a sales clerk. Subsequently, some of his photographs were exhibited at the Pierpont Morgan Library and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, reviving an interest in this nearly forgotten photographer. And this rediscovery happened in a very unusual social and political context. The year before, two hundred Native Americans seized Alcatraz in November of 1969 and occupied it for almost two years. After all, they argued, the prison island was like home, the reservation, “the rez,” “It has no running water; it has inadequate sanitation facilities; there is no industry, and so unemployment is very great; there are no health care facilities; the soil is rocky and unproductive.” In 1970 author Dee Brown published Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, a revisionist version of how the West was won, a book so important that over forty years later it still informs contemporary thinking about American internal colonialism and imperialism. Indeed in 1973, two hundred Native Americans seized the town of Wounded Knee to call attention to the plight of tribes trapped on reservations and to the difficulties faced by so-called “urban” tribal members who faced constant discrimination. Therefore a contemporary understanding of Edward Curtis was unfolding during a period of intense social and political activism within the Native American communities themselves.

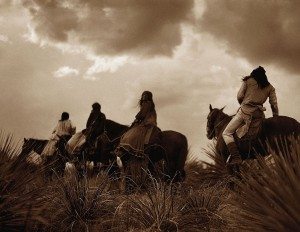

Edward Curtis. Before the Storm

Writing for the American Masters series for PBS, George Horse Capture was sympathetic to Curtis and praised his work, but, among other observers, the posthumous reputation of Edward Curtis has suffered at the hands of his many critics. In a well-known article, “Socioacupuncture: Mythic Reversals and the Striptease in Four Scenes,” a member of the Chippewa author, Gerald Vizenor, one of the most severe critics of Curtis and his methods, described the representational clothing of the Native Americans pictured by Curtis as a kind of reverse striptease,

“Tribal cultures are colonized in a reversal of the striptease. Familiar tribal images are patches on the ‘pretense of fear,’ and there is a sense of ‘delicious terror’ in he structural oppression of savagism and civilization fund in the cinema and in the literature of romantic captivities. Plains teepees, and the signs of moccasins, canoes, feathers, leathers, arrowheads, numerous museum artifacts, conjure the cultural rituals of the traditional tribal past, but the pleasures of the tribal striptease are denied, data-bound, stopped in emulsion, colonized in print to resolve the insecurities and inhibitions of the dominant culture..Edward Curtis possessed romantic and uninvited images of tribal people in his photographs. Posed and decorated in traditional vestments and costumes, his pictorial tribes are secular reversals of a ritual striptease, frozen faces on a calendar of arrogant discoveries, a solemn ethnocentric appeal for recognition of his own insecurities; his retouch emulsion images are based on the ‘pretense of fear’..Tribal cultures have been transformed in photographic images from mythic time into museum commodities.”

As Mike Gidley noted, Vizenor spoke in a “collective persona,” the collective we of the “North American Indians,” when he said, “..we were caught dead in camera time, extinct in photographs, and now in search of our pst and common memories we walk right back into these photographs.” The problem for these kinds of critiques is that they tend to assume that the Native Americans themselves had no agency. Many times, Curtis respectfully asked permission to photograph individuals and to record religious ceremonies considered both sacred and secret. When permission was granted, the effect was that Curtis was actively joining the tribes in their defiant attempts to preserve their own rituals. If and when one views the archive or collection of Curtis as a joint effort between the actors and the playwright, then the interpretation shifts from that of surveillance to cooperation. Curtis, who got his start as an ethnographer photographing the indigenous peoples of Alaska, was trusted by the Plains Indians and the tribes of the Pueblos.

President Theodore Roosevelt, who was in charge of the government that was working so assiduously to erase the past lives of the Native Americans mourned the passing of the distinctive culture, embodying the odd duality of white Americans at this time in his support of Curtis. The very language employed by Curtis was the language of painting, soft-focus and romantic and nostalgic, the harsh glitter of a mechanized document gentled in the development process into a suitable vehicle for what he called “the old-time Indian.” In an odd twist of fate, as recounted in the lovely film by Anne Makepeace, Coming to Light: Edward S. Curtis, contemporary members of the tribes visited by the photographer a century ago today look to his images for information of their now-lost cultures. It seems to matter little that there were slights of hand involved, the removal of elements of modern life in the darkroom, and the fact that when Curtis was on the reservations, missionaries and Indian Agents were in charge, and the traditional clothing of the Native Americans were, even then, regarded as “costumes.” What is important to contemporary Native Americans is that this work by Curtis is all they have left of their past lives.

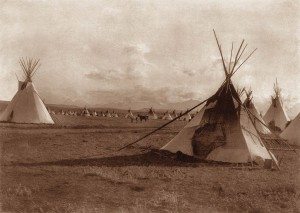

Edward Curtis. Piegan Encampment

The importance of native agency and participation become even more apparent in Curtis’ film on the Kwakiutl culture of Vancouver. This overly dramatic and often fictional movie would not have been possible if the tribes people had not carefully recreated their own traditional crafts, clothing, and rituals, including a recreation of a banned and illegal potlatch ceremony. This money-making enterprise was anything but accurate, and antics, such as renting a dead whale for a culture that never hunted whales, marred the supposed ethnographic nature of the work. Although In the Land of Head Hunters (1915) was a forced narrative, it is clear that the Kwakiutl who took part enjoyed playing their roles, however dramatized by the stern director. It is no accident that when Curtis took a break from his project on the “vanishing” Native Americans, he went to Hollywood and even worked with C. B. DeMille. Curtis doggedly pursued his dream until he published his final volume in 1930, exhausted and totally without money and largely unappreciated. Despite the critiques of his methodology and the evidence of a imperialist mind which leaves its traces on his photographs, what is important now is that enough truth and authenticity was captured, if only in the intent of the maker, and that the images of Edward Curtis exist today and hybrid concoctions–works of art and works of representation and historical documents.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.